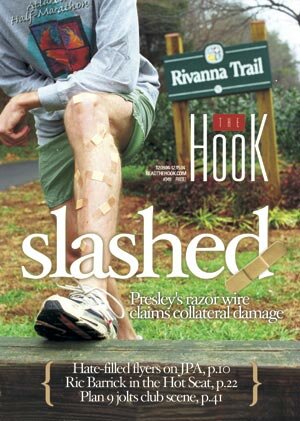

Slashed: Presley's razor wire claims collateral damage

Injured trail-goers speak out

Two months after the City's stunning courtroom defeat in the long-running razor-wire case, the controversy is far from over. City police have undertaken surveillance to nab trespassers. And after months of rumors, evidence has emerged that at least two trail-goers– including one of the four-legged variety– have been slashed by the wire in the yard of widow Shirley Presley.

Is Presley headed for another showdown with the City?

A razor-thin victory

Just how did a septuagenarian described by one friend as a "kind, caring, thoughtful, Christian lady" find herself at the center of a property-rights maelstrom? It all began with a civic project: the Rivanna Trail.

As part of its quest to create a continuous 20-mile trail around the city, the nonprofit Rivanna Trails Foundation obtained easements from waterfront property owners beginning in the early-'90s. But, in what the Foundation has called an "oversight," no one obtained the permission from the homeowners on Bland Circle, a cul-de-sac of compact homes on a high bluff over the Rivanna.

While some Bland Circle residents forgave the lapse and eventually gave permission, Presley grew more frustrated with– and fearful of– the increasing number of hikers crossing her property.

In the summer of 2002, the Foundation, acknowledging Presley's property rights, created a bypass redirecting hikers away from her property and onto the asphalt of River Road and Locust Avenue.

The posted detour, however, wasn't enough to keep interlopers away. In early summer 2002, Presley erected a large brush pile across the trail to deter users, many of whom were frustrated by the blockage of a riverfront route that had allegedly been in casual use for decades.

One outraged biker expressed her discontent to a Hook staffer investigating the situation.

"I'm from California," screamed the woman, dragging Presley's brush off the trail, "and we believe in freedom!"

Such vigilante tactics by angry hikers apparently prompted Presley to beef up the pile, and the mound of trees and brush eventually swelled to at least five feet high and around 10 feet deep. Yet the trespassing continued.

After several more confrontations with interlopers– including one that occurred with police present, according to her lawyer– Presley took protection of her property to a new, more extreme, level, erecting not one– as has been previously reported– but two parallel strings of razor wire approximately 60 feet apart across the trail near each edge of her property.

After the razor wire went up, "the trespassing essentially stopped," says Presley's lawyer, Fred Payne. But in August 2003, a new problem arose.

Alerted to the new barricade, the City cited Presley for a violation of the City Code section regulating barbed wire on residential property which gave her six months to remove it. She refused. In response, City Council rewrote the law to make it more clearly applicable to residential situations, and in April 2004, Presley was cited under the new razor-wire ban.

The case finally went to trial– with 13 witnesses subpoenaed, including this journalist– in Charlottesville District Court on October 29.

After three hours of hearing Payne's and Assistant Commonwealth's Attorney Ron Huber's version of events, Judge Robert H. Downer announced his verdict: The case against Presley was dismissed.

The decision, rendered long before most witnesses had taken the stand, deprived viewers of certain intriguing testimony. For instance, one of Presley's neighbors was allegedly set to testify that she had seen Craig Nordenson, the "coal tower killer," on Presley's property before he committed his infamous double homicide in April 2001.

City zoning inspector Jerry Tomlin, who conducted much of the City's investigation into the razor wire, was questioned about whether he trespassed to get photographs of the barricade, a point he says is moot.

"I do have the authority under [Virginia Code section] 36-105 to go on the property," says Tomlin. "The thing that I cannot do without a search warrant is to go inside a dwelling."

In the end, however, it was not an issue of trespassing or safety that decided the case, but one of semantics.

"No person shall erect or maintain a fence, wall or other barrier wholly or partially enclosing any lot or premises within the city, where such fence, wall or barrier is made of or includes barbed ends, barbed wire or razor wire, or any similar materials," the code states. The only exception is on commercial property, where such barricades are allowed but must be at a minimum height of six feet.

Judge Downer, while acknowledging that the City's intent is clear, accepted Payne's argument that Presley's wire– which runs in a straight line– neither "encloses" nor "partially encloses" her property. City officials, he said, would have to rewrite that portion of the code if they want to require that the razor wire be removed.

"We were disappointed, to say the least," said Huber, calling the Judge's interpretation an "inexplicably narrow" reading.

Presley 1, City 0

The Hook began following this case on July 4, 2002. With each passing dispatch from the razor-wire war, letters to the editor multiplied. Many correspondents weighed in on the side of property rights.

"There's a word for using someone else's property without asking permission," wrote Libertarian Richard Sincere. "It's called stealing."

Jan Bartlett wrote, "Mrs. Presley deserves to be left alone and remain secure on her own land, which is her Constitutional right. It's a big world; walk somewhere else."

"What have we come to?" asked Al Zappa. "The city rewriting laws to find something to convict her of when she is simply defending her land, and a judge saying they didn't rewrite the law correctly, case dismissed. How poetic!"

Others, however, contended that razor wire anywhere near ground level is unacceptable for any reason.

"I wonder if lovable Shirley 'Razorwire' Presley has considered land mines to interdict the Rivanna River Trail?" wrote a caustic Hamlin Caldwell Jr. "A few 'bouncing Betty's' and 'toe-poppers' might take care of those heinous hikers and their pooches and smaller children."

Payne has shown little sympathy for anyone injured on his client's property. In fact, when recently informed of a possible razor-wire injury, Payne had a simple reply.

"I would very much like to know the name of that person," he said, "because if the person was injured, we would charge them with trespass."

Insult to injury

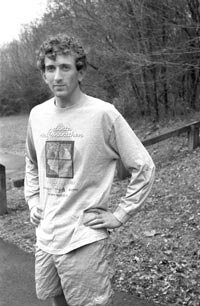

The name of that person is Peter Dunn. He says that when he read Payne's comments in the November Hook story, he was surprised that Payne would prosecute him– especially since he says he's already paid a heavy price for his missteps.

Dunn's story began last January when he decided take an exploratory run on the Rivanna Trail. Dunn, then a third-year UVA student who had never been on the trail before, started out at Riverview Park at the end of Chesapeake Street, passed by the VFW Lodge on River Road, and continued north beside the winding Rivanna along a narrow, rutted stretch of the trail.

"I wanted to see where it went," he explains.

When he arrived at Presley's barricade, he was surprised. "This," he thought, "is really weird."

He stopped and stretched while considering his options: turn around and head back or go over the barricade and continue his run.

He chose the latter. "I couldn't think of a good reason not to," he says, though today he admits he "should have known better."

Dunn placed his right leg over the razor wire without incident. But as he pulled his left leg over the coil of blades, he says, a razor cut him deeply behind his left knee.

As people who have cut themselves shaving know, razor cuts often cause little initial pain. Dunn's slice was no different– though the size and angle of a Presley blade are a bit different from a Gillette.

Thinking the wound was superficial, Dunn says, he removed his shirt to create a makeshift bandage. He tied it around his leg and finished his run.

But when he arrived home and removed the shirt, he found blood coursing from the wound.

"I bled enough on the kitchen floor," he recalls, "that my roommates insisted I go to the emergency room.

There Dunn learned that he'd severed a small artery. He received four stitches to close the wound and left the ER a sadder but wiser man.

Dunn doesn't ask for sympathy. "In my case, I knew I was asking for trouble," he says. "But animals and kids don't know."

A second victim

Region Ten social worker Buzz Barnett set out for a "really long walk" last spring with Lucy, his two-year-old golden retriever. They entered the Rivanna Trail at the Greenbrier neighborhood and made their way southeast to Pantops, where Barnett's wife planned to pick them up near Free Bridge.

Barnett concedes that he saw a posted warning that the Trail was closed ahead, but "it was getting late," and he didn't want to keep his wife waiting, so he and Lucy continued.

When he reached Presley's property, he says, he also was surprised to see the razor wire and accompanying signs. Rather than backtracking and delaying his trip further, he and Lucy went down the bank toward the river to try to bypass the blockade– an undertaking that proved disastrous.

"The bank is really steep," says Barnett. "We almost fell in."

When they re-climbed the bank, Barnett says, he found himself in an even more perilous situation: he and Lucy were trapped between Presley's two stretches of razor wire. While Barnett tried to figure out their next move, Lucy, he says, "took off and jumped through it."

Like Dunn, Barnett didn't immediately realize that the dog had been cut or the seriousness of the injury. And Lucy didn't seem to realize what had happened. After Barnett made it over the second set of coils unharmed, he threw a ball into the river for Lucy to retrieve as they continued along the trail.

While she was in the water, however, Barnett realized something was wrong.

"She was whimpering," he says, "and she almost didn't make it back to shore."

When she did clamber up the bank, "I saw all the blood," Barnett says. The razors had slashed the dog's back, stomach, and legs– in some places all the way to the muscle.

Lucy spent the night in an emergency clinic where vets stopped the bleeding with stitches and placed drains in the wounds. The bill for her injuries totaled $700.

Lucy has since fully recovered. Like Dunn, Barnett acknowledges he shouldn't have crossed the blockade, and he admits that Presley has a right to keep her property private. But he questions her methods.

"I wish she would use some other means," says Barnett. "A wall, a moat. Razor wire seems excessive."

He also worries about future injuries if the City can't get Presley to remove the wire.

"A dog could get hung up on the razor wire and just die there," he says.

Payne has been unmoved by the subject of suffering animals. "If you let your dog run," he has said, "I don't have much sympathy."

Interrogation

While Presley is taking a hard line against anyone who crosses her property, and her lawyer has accused the City of trivializing her fear of trespassers, the Hook recently learned, rather directly, how the City has begun acting on her concerns.

On Wednesday, December 1, Charlottesville Police Detective Blaine Cosgro arrived unannounced in the Hook office to interrogate Editor Hawes Spencer.

"Is this you?" whispered Cosgro, pointing to a grainy photograph of a camera-toting man allegedly trespassing on Presley's land on November 1. Spencer professed his innocence, and Cosgro left as quietly as he'd arrived.

"I think he thought it was me because a file photo I'd taken of the razor wire had run in the paper that week," says Spencer, who notes he has not been near Presley's property since June.

Charlottesville Police Chief Tim Longo– one of the city officials subpoenaed by the defense in Presley's trial– confirms that his department has been quietly conducting photographic surveillance on Presley's property this fall.

"We've certainly been helping her with the problem she brought to our attention," says Longo.

Though he declines to detail the methods used, he says any citizen wishing to protect his or her property can obtain police help by signing a "private property trespass enforcement letter," a document that details the conditions under which the police can operate on the private property.

"It's a very limited type of agency," says Longo. "It's only for purpose of enforcing the no-trespass."

Through attorney Payne, Presley declines comment.

But cynics might be forgiven for wondering if the camera-in-the-woods effort may be an attempt to forestall a lawsuit. Payne has repeatedly hinted at such a move, most recently after his courtroom victory in the criminal case against Presley.

The City, he said ominously, "is only going to push this lady so far."

A new tactic?

Despite losing the suit in District court, the City is regrouping and considering its options in dealing with Presley's razor wire. City Attorney Lisa Kelley, who wrote the portion of the code that failed to block the wire, says they have not reached a decision.

But inspector Tomlin says the city won't let the issue die just because Presley won the first battle.

When pressed, he says it's conceivable that Downer didn't realize there were two stretches of razor wire– a fact that could have influenced the judge's interpretation of "partially enclosed."

"The question never came up to me in court," says Tomlin.

Also of note, says Tomlin, is the fact that the 31-foot stretch of razor wire at the southwest corner of Presley's property extends onto a neighbor's land. The listed owner of that River Court property, T. Ryland Moore, says he was not aware of the razor wire's presence until the City contacted him. He has since sold the property, he says, and has no opinion on the razor wire. The new owner could not be reached for comment.

Tomlin slips in one comment that may be a hint at the city's plans.

"When the case comes to court," he says, "we'll also remove it from his property." Hmmmm.

Like Kelley, Tomlin will not reveal any specific actions the City may be planning, perhaps because, Tomlin says, the City is "continually getting threats" from Payne. But there are several obvious possibilities.

The first is that the City could rewrite the code to remove any ambiguity. Once a new code is finalized, Presley would have to be notified once again that her razor wire is in violation.

Another option would be eminent domain; the City has the right to take, or "condemn," land for public purposes such as the planned extension of the asphalt portion of the Trail. Indeed, long-range plans indicate that linking City parks with an accessible trail is one of the city's highest pedestrian priorities.

If there are still other options, no one is revealing them at this time, but Tomlin offers one promise.

"We have not gone away," he says. "We're still obligated to protect the people of this community."

Shirley Presley could have faced at least a $2500 fine.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

This photo earned the Hook editor a mild interrogation.

FILE PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

Slashed by razor wire, UVA student Peter Dunn learned a sharp lesson.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Lucy was cut to the muscle by Presley's razor wire.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Charlottesville Police Chief Tim Longo confirms police surveillance on the Presley property this fall.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The razor-wire controversy sharpened considerably as Hook readers sent in their pointed opinions on the property rights run-in.

The RTF created a detour around Bland Circle properties in 2002.

MAP BY CHRIS CONKLIN

#