Blenheim brouhaha: She Sherwood like her name back

Making a stink and taking names: Millionaire develops farmettes... and pigpen

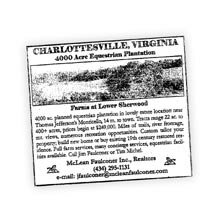

A Wall Street Journal ad announcing the sale of a "4,000 acre planned equestrian plantation" caught JoAnn McGrath's eye. The ad, offering tracts ranging from 22 to 400+ acres, seemed to answer the burning question in her Scottsville-area neighborhood: Why has telecom magnate Thomas Sullivan– despite a 150-signature petition against it– been so determined to widen and pave historic Blenheim Road?

Sullivan told the public in March that he was simply stitching together some farms in the Scottsville area– and that he's not a developer.

"The land in front of us has been broken into four 20-some acre lots, and one to the east has been broken off," says McGrath's daughter, Paige. "How is that not development?"

But it was another aspect of Sullivan's marketing pitch that really piqued the McGraths. It wasn't the "lovely estate location near Thomas Jefferson's Monticello." And it wasn't the promised "concierge" facilities. (What on earth, she wondered, does a concierge do in Keene?) And it wasn't the planned equine center.

It was the bold headline that advertised the land Sullivan is selling as "Farms at Lower Sherwood."

Her farm.

Long before Sullivan or the McGraths moved in, their current properties were part of an old estate called "Sherwood." In 1969, an owner sold part of that land as "Lower Sherwood."

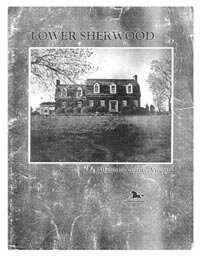

That was the name on the glossy brochure produced by a real estate firm marketing the 94-acre farm in the mid-1980s when the McGraths bought it.

McLean Faulconer was that firm, the same one now marketing Sullivan's farms. Company principal Jim Faulconer says Sullivan has a right to the name and downplays any confusion. "We don't call it Lower Sherwood," Faulconer explains. "We call it The Farms at Lower Sherwood."

Since 1986, the McGraths at Lower Sherwood have been raising and selling llamas to fanciers of the exotic beasts from New York to New Zealand. In addition, their 100+ herd at Lower Sherwood attracts visits from school groups and other animal lovers.

Who would confuse a llama farm with an equestrian farm? The possibilities, it seems, are endless.

"We've had cement mixers, delivery trucks, potential buyers, everyone coming to our house," says Paige McGrath.

From Route 20 to the McGraths' driveway, three separate signs point the way to "Lower Sherwood Llama Farm," or just "Lower Sherwood." The McGraths say they saw no similar markers on the land that's for sale– until Thursday, December 9. On or before that day, a large sign suddenly appeared near the entrance to Sullivan's development.

The McGraths worry that any legal challenge they might mount to use of the name would be futile because of Sullivan's money.

"I can't fight this," says JoAnn McGrath, acknowledging that the waters have been muddied by the parceling that's happened over the years. "But the fact that he has appropriated it when there's already a farm doing business as Lower Sherwood seems a little high-handed."

Thomas Sullivan is the McGraths' neighbor, although JoAnn McGrath describes the acquaintanceship more ominously: "We're surrounded by him on three sides."

While she estimates the distance to Sullivan's home, "Mt. Pleasant," as three to five miles, the McGraths feel that space has steadily compressed since the former telecom magnate began his buying spree in late 2003.

Sullivan was once one of the two top executives at Telecorp PCS, a wireless phone company that went public in 1999. Two years later, when the company was sold to AT&T Wireless, Sullivan pocketed about $45 million. While he keeps his primary residence in Maryland, Sullivan now controls some 5,500 acres of land in Keene, a bucolic burg that's also home to rock star Dave Matthews and vintner Patricia Kluge.

As reported in the Hook's August 12, 2004, cover story, "Highway man," Sullivan– over the objections of many neighbors– has widened and paved the last gravel stretch of historic Blenheim Road, aka Route 795. Besides destroying the canopy of trees that once characterized the rural lane, Sullivan's effort– which he financed himself– has provoked a lawsuit by a neighbor whose trees he uprooted, and has raised fears of development in this rural retreat.

"Speculation has run rampant," says Jeff Werner of the Piedmont Environmental Council, who witnessed the controversy at three Board of Supervisors meetings. While Sullivan has announced his intention to put land into conservation easement, no portion of the 4,000 acres now on the market has been so designated, according to another PEC executive.

Whether easement or development, no one really knows, because Sullivan communicates with neighbors (and the media) only through a spokesperson, Kim Atkins. According to Atkins, Peter D. Nielsen, a previous owner, had already chopped Sherwood into pieces, and Sullivan is "putting it back together." He describes the parcels he's selling as a "community farm concept."

With his total land holdings of over 6,000 acres– 4,000 of which are currently for sale– the emerging picture seems to be what skeptical residents have long suspected.

Considering the "concierge" and full farm services promised in the ad, the McGraths wonder if they'll soon be surrounded by a gated community. But Sullivan's spokesperson Atkins says "The Farms" won't be. While Blenheim Road neighbors are, technically, part of the new "community farm concept" unfolding around them, the anti-growthers aren't the only ones who feel left out.

Even some folks who signed a pro-paving petition that Sullivan circulated say residents have been largely excluded from the process that could permanently alter, if not totally redefine, their neighborhood.

"I honestly don't know how we can be in favor of it when we don't know what he's going to do," says Robert Fulcher, who signed the petition in support of the paving as part of an agreement that prevented Sullivan from further destroying trees in Fulcher's viewshed. "We've not had a direct communication with this man," he says.

What Sullivan did to one neighbor's views (and her nose) has yet to be resolved.

Debbie and Mike Donley live on an 11-acre parcel adjacent to Sullivan's cattle farm. Like the McGraths, their land is surrounded by Sullivan's on three sides. While the lowing of cows at the nearby feedlot isn't always music to their ears, it's Sullivan's most recent addition that has them steamed.

It was less than a year ago, the Donleys say, when they noticed workers building what appeared to be some sort of large animal enclosure less than 100 yards from their house.

A big pen. A pig pen.

When Debbie Donley asked, the two workers laughed and told her they were putting up a shelter for a pair of soon-to-arrive pot-bellied pigs. The Donleys protested, pointing out the proximity to their home.

The pen was right along their fence line and far nearer their house than to Sullivan's own barn.

"'We thought it was pretty close to your house," Debbie Donley recalls one of the workers saying, "but that's where we were told to put it."

The pen is about 15 feet from where the Donleys park their car, and lined up "dead center" with their home. "You couldn't line it up any closer," she says. She believes the pen is retaliation for their "making a stink about saving that road."

Angry, she confronted Sullivan about the pigs at a county board of supervisors meeting in early 2004. Donley says Sullivan replied that his daughter wanted to keep pot-bellied pigs– sometimes called "miniature" pigs– which can weigh up to 175 pounds when full-grown.

Why, Donley asked, when Sullivan had thousands of acres, did he place the pigs right next to their house? Why not move the pen closer to Mt. Pleasant so his daughter wouldn't have to travel two miles to visit her new pets?

Donley she says she wouldn't have complained about the arrangement "if he had only 30 acres." Her husband, meanwhile, "called everybody he could," but found that the local authorities were unable to intervene.

Atkins says that the pig pen was located to be near the Sullivans' existing barn and feedlot– and denies that retaliation played any role in the location.

The Donleys say their main concern is the family drinking water, which experts advise should be at least 100 feet from any animal enclosure. They measured and found that the distance between the pen and their well was only 82 feet. If they're worried about contamination, the Donleys say they were told by officials, they'll have to keep testing the water themselves. But what about that 100-foot buffer?

Under Virginia law, the only question to be asked in such cases is which came first, the pigpen or the well? If the well is already in place, no rules govern the space between them. If the pigs came first, however, a minimum 50-foot separation is required. That is, a margin of safety applies only to the construction of new wells– not new pigpens.

"We don't enforce pigpen regulation," says Michele Napper of the regional health department, adding, "There isn't any regulation as to where you can place a pigpen." Of course, the department "strongly recommends" the pigs be housed at a greater distance from the well.

Mike Farish, a veteran farm manager, says he sold the "pig equipment" to Sullivan over a year ago. Farish seems surprised by the conflict over a few pigs since Sullivan's cattle also roam near the Donleys' property. Other neighbors, he says, keep livestock near their wells without any drinking water contamination. Besides, says Farish, "They're just novelty pigs."

Now that the leaves are off the trees, the Donleys have an unobstructed view of the novel creatures. "It's enough to make me move," says Mike Donley. "I let the weeds grow up and try not to look over there."

Such scenery might not be so unusual for country residents, but the Donleys can only wonder why Sullivan didn't opt to enjoy the barnyard view from his own living room window. And the McGraths wonder what they'll next learn about their neighborhood in the Wall Street Journal.

Just before press time, Sullivan called the Hook office.

"I'm not going to move the pigs," he says, repeating several of the defenses offered by his spokesperson. "You can't please everyone. People don't like change."

As for the claim that he has become a developer, Sullivan points out that at least two of his neighbors have recently subdivided their properties, and then deadpans, "You mean I have to hold onto the 4,000 acres for the rest of my life?"

Even as they watch Sullivan's changes redefine the hamlet of Keene, the McGraths, the Donleys, and others might be forced to admit that their neighbor is operating within his rights.

JoAnn McGrath acknowledges this. "But just because you can do something," she says, "it doesn't mean you should."

As seen from the property of Mike and Debbie Donley, Thomas Sullivan's pigpen is just a few footsteps away.

This ran in the October 29 edition of the Wall Street Journal .

On Tuesday, December 14, the day this story went to press, JoAnn McGrath got a surprise phone call from Kim Atkins demanding the removal of the sign that has directed visitors to McGrath's llama farm since 1986. "The arrogance is just unbelievable," says McGrath.

When McLean Faulconer was selling what became the McGrath's farm in the mid-'80s, they produced this glossy brochure for "Lower Sherwood Farm." Now, that same firm is helping Sullivan market his equestrian properties as "The Farms at Lower Sherwood."

For 18 years, the McGraths, JoAnn and Paige (shown here) have raised llamas as Lower Sherwood Farm.

Paige McGrath has the right to walk and drive on the shared half-mile driveway over Sullivan's land. "They have not only taken the name of our farm– now they're threatening to take the sign down," says her mother.

Sullivan joins Dave Matthews and Patricia Kluge in calling the Keene area home.

After dealing with a year-ago "stop work" order from the County, Sullivan's paving and widening near his horse farms has reshaped Blenheim Road.

Buy a horse farm– get a concierge! (Sullivan declined to be photographed for this story.)

"Raising champion llamas since 1986," says the McGrath's site, llamalife.com

ALL PHOTOS BY JEN FARIELLO

#