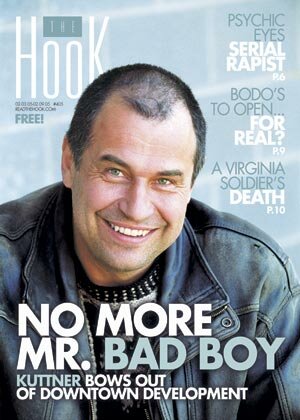

No more Mr. Bad Boy: Kuttner bows out of downtown development

PHOTOS BY JEN FARIELLO

The titles on the bookshelf in Oliver Kuttner's office tell us everything we need to know about the man. Existentialism from Dostoevsky to Sartre and Maserati 3011 are inches apart, while on a second shelf Men are From Mars, Women are from Venus and Living with Contradiction, a book on the "controversies of feminist ethics," round out the collection.

"I've read most of them," Kuttner chuckles.

Clearly, this is a guy with diverse interests, not least among them race cars and a new family– he married last year and now has two sons. But he's no longer pursuing the one interest he may be best known for locally: downtown development.

"I'm kind of done here," sighs Kuttner, simultaneously enduring an in-person interview, answering the phone, juggling his squirmy one-year-old son, Christoph, on one knee, and supervising his five-year-old, Ronnie, who's brandishing an electric drill and boring holes in his brother's plastic riding toy.

Multi-tasking is a skill 43-year-old Kuttner has honed in numerous complicated building undertakings. And managing two rambunctious kids is nothing, he says, compared to the stress of cutting through Charlottesville's bureaucracy during the development of such projects as the Terraces and the Downtown Tire building on Water Street.

"It's such a process," he says of his many battles with city officials. "It's like wasting money for nothing; it's not very rewarding."

Kuttner's struggles with the city have been well documented. During the 1999-2002 construction of the Terraces– retail, office, and upscale apartments in the former Woolworth's building between Water Street and the Downtown Mall– Kuttner dealt with almost constant delays. At one point during the renovation, the city's stop-work orders piled inches high. Particularly frustrating, Kuttner says, was the amount of time it took for his plans and requests to be processed.

"Everything is talked about 100 times," he says. "By the time you're done, you've spent 10 or 20 percent of the budget on paper."

And it wasn't only the cost of equipment and additional plans that drove him crazy. Keeping a large workforce on the payroll during delays– some as long as 90 days– was difficult. But Kuttner says he never laid anyone off.

"What was I going to do?" he asks. "Say, 'Sorry, you're not going to eat this month?' No."

Despite the delays, Kuttner succeeded in building a residential tower over, under, and behind an operating Woolworth's/Foot Locker store– including underground utilities. "I finished 95 percent," he says. But it was a family project– the building is co-owned by Oliver, his younger brother Daniel, and their father, Ludwig– so Daniel took the reins when Kuttner began work on the Cavalier Beverage building.

Just down Water Street, the Downtown Tire building renovation was another story. Kuttner, sole owner of that building, finished the project against the odds. When the Board of Architectural Review rejected his plans for external modifications, Kuttner simply left the giant garage doors in place and built storefronts within the exterior walls.

Then the BAR, in a surprising move, supported the concept. "I thought it was great," says former BAR chair Joan Fenton, of the solution she calls "incredibly creative."

The city's head of neighborhood planning, Jim Tolbert, calls Kuttner a "good friend," though he gently alludes to some of the difficulties and delays endemic to many Kuttnererian projects.

"He marches to his own drummer," says Tolbert.

Is he surprised by Kuttner's decision to bow out of the development scene? "I guess so," Tolbert replies.

Is he disappointed he may not get to work with Kuttner again?

After a pause, Tolbert offers a carefully worded response: "Let me just say, I think what he's done has turned out very nice."

Like Tolbert, Kuttner is careful not to let his criticism become personal. "There's nothing wrong with any of those people," he says. "The system is just too bureaucratic, in my opinion."

Kuttner's other major downtown project, the Glass Building on Second and Garrett streets, entailed less red tape. Because it's on the other side of the C&O tracks, it's outside the downtown historic district and therefore not subject to BAR regulations.

Kuttner says he enjoyed that relative freedom.

The building's huge exterior expanses of multi-paned glass and walls of steel create an industrial aesthetic tempered by warm terracotta-stained concrete floors inside.

During a construction tour in 2001, a proud Kuttner gestured broadly. "This," he announced, "is what I can build when nobody f***s with me!"

That building has also been credited with revitalizing the area south of downtown and paving the way for the "Warehouse District" complex of upscale shops which includes Posh, Moxie hair salon, and Sammy Snacks, a dog-food boutique.

More recently, Dave Matthews Band manager Coran Capshaw has announced a massive overhaul of the former Ivy Industries building on Garrett Street. With ACAC health club anchoring the huge complex that will include two residential towers, the Capshaw center– between Garrett Street and Monticello Avenue– could cement the "south of South Street" area (irreverently known to some downtowners as SOSO ), as a happening destination in its own right.

Such upscale developments near the Friendship Court subsidized housing project might have been unthinkable pre-Kuttner.

"He was always ahead of his time," says Alana Woerpel, whose custom fabric shop, Alana's, recently relocated to the former Gleason's tractor repair building on Second Street.

"He's very accommodating and very fair," says Woerpel, who notes that during her time as a tenant in Kuttner's Downtown Tire location, he allowed her to enlarge her store from 900 to 2,500 square feet. And he encouraged her when she expressed interest in buying the tractor repair building.

Fortunately, says Woerpel, she purchased the building after the renovations were complete, so she avoided much of the red-tape wrangling Kuttner had to endure.

"I did find after the whole process was done that dealing with the city is frustrating," she says, "and I can understand his frustration."

Developer Lee Danielson may also be uniquely qualified to sympathize with Kuttner's frustration. When, in the mid-1990s, Danielson conceived of a Downtown Mall movie theater and ice park, he believed a Mall vehicle crossing was crucial to the success of both entities. Like Kuttner, he spent months battling the city, although he eventually prevailed.

Given his own experience downtown, Danielson says he respects Kuttner's "creative" development style.

"There are many approaches to do things," says Danielson, "and I think that he has given a lively color to the community."

These days Kuttner is taking that color on the road. He's developing an old warehouse in Lynchburg– a city he calls "much easier" to work in. Closer to home, Kuttner is focusing his energy on the Starlight Express, a luxury bus company that makes nonstop round-trips from Charlottesville to New York City every weekend and most holidays.

On this project, Kuttner has teamed with Root 66 Root Beer founder David New, and the two are encouraged by the response they've received– particularly after launching a full-service website, nycshuttle.com, where bus schedules are listed and tickets can be purchased.

"Forty-five minutes after the site went up," raves New, "money was coming in."

The site also provides maps and links to accommodations and activities in the Big Apple.

If all continues to go well with the Charlottesville Starlight operation, New and Kuttner plan to expand the business, starting with buses out of Harrisonburg and Winchester. From there, the sky may be the limit.

"We're trying to compete with USAir," says Kuttner. "We're onto something."

When he's not driving a bus, Kuttner likes to get behind the wheel of a racecar– in particular, a new Daytona prototype he had built in 2003. Though he has raced the car himself, more recently he's has been leasing it. On February 7, Kuttner says, NASCAR stars Bobby and Terry LaBonte will take over the driving duties.

"It's pretty cool," says Kuttner, relieving the restive Ronnie of the power drill in preparation for a relatively sedate 55-mph spin south to check on his warehouse project in the Hill City. While he's there– always multitasking– he'll swing by the children's museum, two small boys in tow.

Even without new downtown developments, it's clear Kuttner intends to remain a driving force.

#

The Terraces

Though it's hard to believe by looking at it, the Terraces is the largest multi-use building downtown, with more than 60,000 square feet of residential, retail, and office space. Kuttner had a vision for the building, one that didn't involve cutting corners.

"He invested a lot of money in the exterior materials of the building," says former mayor Maurice Cox, citing the use of regenerated stone, brick, cornices, architectural detail, and high quality windows. Cox says such a building is good for the whole community.

"That is always where a city would prefer that developers invest their money," says Cox, "where the public can see the difference."

Construction of the Terraces took nearly three years, with particular delays over the under-grounding of utilities and Board of Architectural Review approval.

Kuttner hired Cox's architecture firm, RGBC, and in particular Cox's wife, architect Giovanna Galfione, to get him through the Board of Architectural Review process. (Architect David Kariel handled the building permits.)

Galfione was unavailable for comment, but Cox says the first BAR hearing went very well.

"They said it was the best presentation they'd ever seen," he recalls.

Kuttner, Cox adds, was "flying high because no one had expected him to do it in such an accomplished way."

But the smooth sailing didn't last.

The BAR, says Cox, was "constantly looking over [Kuttner's] shoulder to make sure what he had presented was what was actually getting built."

Those rigid guidelines don't mesh well with "the nature of a construction site," Cox says, nor with Kuttner's flexible style.

"He was always having to go back [before the BAR] for even the most minor change he wanted to make," says Cox– or in some cases, a change he'd already made.

The most memorable conflict arose in the summer of 2001 when Kuttner installed two reclaimed Gothic arches on the Second Street side of the building. He believed the arches added an interesting design element.

But when the BAR discovered the improvisation, members forced him to remove the arches. He eventually did so, but not without a protracted fight.

Despite the struggles, however, Cox believes the combination of Kuttner's vision and the BAR's rigid guidelines served everyone well.

"Developers tend to get really annoyed with the rules and procedure," says Cox, "but in the end I think the rules help maintain the highest quality of the development."

The Glass Building

For nearly 10 years the Cavalier Beverage Building at the corner of Second and Garrett streets was on the market. The area, south of South Street best known for the Friendship Court public housing project (formerly named Garrett Square), was not a hot spot for development.

But Kuttner and his partner on the project, Lisa Murphy, saw the potential. They purchased the building in 2001 with the goal of creating a wide array of studio, retail, and office spaces. Because it's south of the C&O tracks and therefore not part of the downtown historic district, Kuttner enjoyed relative freedom from city bureaucratic interference.

The project is credited with encouraging more cautious developers to create the "Warehouse District" composed of the Gleason's building and the Downtown Design Center, a string of five-shops including Quince and Posh, in the former Gleason's tractor repair building on Second Street.

"Oliver was always ahead of his time," says Alana Woerpel, who purchased the tractor repair space back in 2003 and who says Oliver's confidence encouraged her to take the south-of-the-tracks leap as well.

Coran Capshaw also got in on the south downtown scene last year with his multi-use development in the former Ivy Industries building. ACAC will fill much of the space with a new, state-of-the-art fitness facility, and upscale condos and a grocery store are also planned.

Downtown Tire

This building, which now houses a variety of upscale boutiques including Eloise, Blush, and Petite Bébé (owned by Kuttner's wife, Kim), as well as Sidetracks music, may be Oliver's greatest creative coup– which he owes to a clever reading of the historic district rules.

When the Board of Architectural Review told him that he couldn't alter the building's exterior and therefore couldn't complete the project he had planned, Kuttner did all renovations behind the giant garage doors– building storefronts inside the original footprint.

Perhaps surprisingly, the BAR applauded the move, which former BAR chair Joan Fenton called "incredibly creative."

The Coal Tower

When Kuttner purchased the property on the tracks between Market Street and Belmont back in 1995, he had big development plans for that and several adjacent parcels: nine buildings with warehouse, studio, and office space. But when he presented the City with his plans for the site in 2000, officials were not persuaded.

"What he submitted was a line drawing on paper," Jim Tolbert told a reporter in 2001.

The city's ire grew when Kuttner began excavating the site without a permit, roughing in a road and digging a foundation. The city issued a stop-work order, and by the following year a frustrated Kuttner had professional blueprints drawn up.

The development, however, never happened.

In 2001, the coal tower became infamous as the site of a double homicide when 20-year-old Craig Nordenson killed 16-year-old Katie Johnson and 20-year-old Marcus Griffin before leading police on a gripping chase through an adjacent neighborhood.

In 2002, Kuttner sold the property to DMB manager and developer Coran Capshaw, who now has preliminary plans for upscale condos.

Water Street Parking Lot

If Kuttner's claim that he's done with downtown development is true, he won't be the force behind any eventual construction on the lot at the corner of Second and Water streets. But he has a vision for the site nonetheless.

In Kuttner's perfect world, the city would subsidize substantial underground parking and would then sell lots above the new parking deck to several different developers, who would put a variety of multi-use buildings on that block.

The benefits of such a plan, says Kuttner, are numerous. First, he explains, because the buildings would be smaller than traditional developments downtown, there would be greater diversity.

"When you do smaller buildings and someone make a mistake," he says, "it's not as bad."

Second, dividing the property into smaller parcels, Kuttner explains, would mean that "smaller people," those with less money, could afford to take on a project.

"That property would require $70 to 100 million to do it right," he says. "There aren't that many people who can spend that kind of money."

And finally, with multiple developers building on the site, "You could stagger construction and use some lots as staging areas," says Kuttner. "At any one time, not everyone is in the market for a new project."

Maurice Cox, for one, wouldn't mind if Kuttner got back into that market.

"Cities like Charlottesville need developers like Oliver," he says, "people who are highly entrepreneurial, inventing things as they go along. When it goes really well, you have quality products like Oliver's."

#

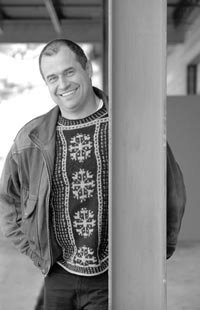

Kuttner

Kuttner at his delay-plagued Terraces project in 2001.

The varied facade of the Second Street side of the Terraces suggests several smaller buildings rather than one hulking mass.

June '01: The controversial Gothic Arch

July '01: Torn out, per BAR orders

Fall '01: The BAR-approved arch

There's a reason it's called the Glass Building.

Kuttner says the Water Street parking lots should be broken into smaller parcels for development with significant subterranean. parking.

Once it housed auto parts, now the Downtown Tire building is home to chic boutiques.

Kuttner believes that new coal tower owner Coran Capshaw will incorporate the coal tower into his plans for upscale condos on the site. "He gets it," says Kuttner of Capshaw.

#