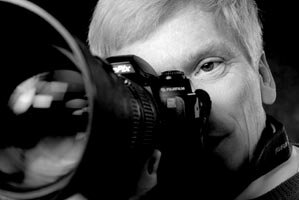

Camera bravura: Carpenter defends digital

In his 37-year career of shooting pictures, master photographer Jim Carpenter has seen technology change from the Speed Graphic of the early 20th century to 35mm film to digital.

But the secret to making good photographs hasn't. "It's still about lighting and composition," says Carpenter, who owns Gitchell's Studio. "You still need the basics, whether digital or film. As a photographer, you need to put depth into photographs."

He looks at two photos of brides, one digital, one from film. "You can't tell the difference. Both have the same lighting design," he says.

Carpenter is an unabashed digital fan. "It lets the photographer be an artist. You can soar with the eagles or stay on the ground and peck with the chickens," he rhapsodizes.

About 95 percent of the weddings, graduations, and portraits he does are digital. And while digital provides a certain instant gratification– and artistic satisfaction– he hasn't found it necessarily easier or cheaper.

"A novice with a megapixel camera– their quality is not going to be as good," he says. And if a digital photo is overexposed, "You can't get that back."

Going digital didn't crop Carpenter's staffing needs. He had to retrain one film technician and hire an extra person. He's always had a lab in his studio, and new digital technology required new printing equipment.

That, in turn, has vastly increased printing potential

"Before we could go from wallet size to a 16-by-20 enlargement," he says. "Now we can print from wallet to 44 inches by 100 feet."

Digital's dominance doesn't necessarily mean the death knell for film. "All things have circles," he says. "Same thing with film." He describes couples who want their wedding albums to look like their parents' album– black and white– whereas "When mom and dad got married, they wanted color, but all they could get was black and white."

Carpenter doesn't worry about the lifespan of digital. He prints photos on archival paper that will be around for 100 years, he says, and he can make them look like oil-painted canvases.

And he's storing images on CDs that– at over three years old– so far present no problem.

Still, he muses, "When a CD is found in a cigar box in an attic in 100 years, people will say, 'I wonder what's on that? We'll just have to dig up one of those old computers to see.'"

"What you can do with digital is phenomenal," says photographer Jim Carpenter.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#