The F-stops her: Digital kills Barracks biz, but threatens magic moments

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Instant gratification. That's why one-hour film processing was just the ticket for those who couldn't wait a week to get their vacation prints back.

Now film photography and processing are tottering down the eight-track path to obsolescence.

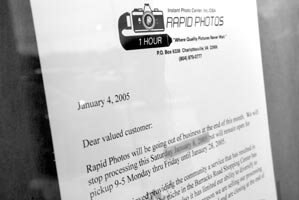

In January, after 22 years in business, Rapid Photos shut its doors. Owner John Thompson says the Barracks Road Shopping Center store was the first one-hour processor in town.

"We made our money printing," says Thompson, "and we had no space to diversify."

Thompson, who sold his digital minilab to Ivy Road-based Cary's Camera, says, "One-hour processing is facing a decline, because with digital, you can see the picture right away. There's a wow! factor. People are thinking, 'This is so cool, why pay for printing?'"

But there's a problem with that thinking. "Digital is not standardized," says Thompson. "The colors are weird. If they were printed, you'd see they weren't quite as good."

He compares digital photography to "poor General Lee defending Richmond" with his lines stretched thin. "The pixels are so far apart that you can see the white of the paper in between them"– if you bother to print them– whereas "there's a huge amount more information captured on a piece of 35mm film," he says.

Rapid isn't the only photography-related business in town feeling the pain. Thanks to the digital revolution, a whole industry based on film doesn't know where it will be in five years.

"We've been affected greatly by digital," says Andrew Rader, whose family has owned Cary's Camera, which opened in 1958, for the last decade. "I do sell cameras and accessories, but photo finishing is our bread and butter."

Rader estimates that Cary's processes 50 percent less film than five years ago, a decline echoed by other independent film processors around town. And he says his business is besieged on another front: cheap processing at big retailers like Sam's and Wal-Mart and CVS.

"My competition is not only my fellow independent retailers," says Rader, who's lowered his processing prices. "It's also the big boxes."

His dilemma is shared by the Camera Center. Started in 1949, it's one of the oldest camera stores in Virginia. Owner Gary Alter, too, calls photo finishing his "bread and butter," and adds that with fewer prints, he sells fewer frames and albums.

"We sell digital to film cameras 100 to one," he says, "and that's not unique to my store."

And even high-end labs that cater to professional photographers are feeling the digital pinch. Nikon, for instance, no longer offers point-and-shoot 35mm cameras except for professionals.

"We've seen an incredible drop in the amounts of film," says John Stubblefield, owner of Stubblefield Photo Lab. "We're still doing lots of film, but digital photographers aren't printing."

In the days of film, if you brought in a roll of 36 frames, Stubblefield printed 36 pictures. "Now with digital, you can edit it down to five pictures," he says.

At the same time, other companies are getting into commercial photo processing. "Even sign companies are doing display work," says Stubblefield. "You can buy an inkjet printer starting at $10,000.

Stubblefield says his firm spent $175,000 for equipment that laser-writes onto archival-quality photographic paper. "If it gets wet, you shake it and dry it off," he says, "unlike an inkjet photo, which would be destroyed."

Retailers like Rader and Alter believe diversification is key to their survival. Scrapbooks are one option, as is printing stacks of personalized Christmas cards. Try that with a toner-gulping Epson or Lexmark.

Digital makes old photograph restoration and retouching easier. Some stores are adding online digital service, or large format photographs. Others are taking photographs, or providing graphics services.

Alter points out one very big problem with digital photography that may surprise some who think that ones and zeroes live forever: "It's not a permanent medium like film."

While film can go bad if it's not processed, and photographic negatives may fade somewhat over their approximately 100-year lifespan, they're unlikely to do what any computer user knows can happen to data: disappear in an instant.

"Hard drives are going to corrupt," says Alter. "It's not 'if,' it's 'when'."

In the old days, people feared fire. Now the catastrophe can be silent– but deadly– for precious memories. "Suddenly," says Alter, "your child's fifth birthday party isn't there anymore."

The lifespan of such "permanent" media as CDs is unknown, but Alter and other experts recommend recopying them every three to five years. He adds, "We print on paper that will last 100 years. That's the best way to keep them."

He worries about the cultural implications of watching 35mm film go down the tubes. "Photography is about preserving memories," says Alter. "What pictures are about is not just the moment, but being able to look at it years later to document your story."

Only 13 percent of all digital photos make it to paper, according to Certified Digital Photo Processors, while 98 percent of film images do.

The biggest job facing those in the industry is educating people about the limitations in the life span of a digital photograph, "so when you want your pictures down the road, they're still there," Alter says.

Ads from mass photofinishers ask, Where are my pictures? and show the image of an empty photo album. Or there's the popular, "I've got 17,000 photos on my computer," says Stubblefield.

Alter notes that unstable inks from home processing will fade away, not to mention that "The photo paper you use at home costs you more than at my store."

He's been a photographer for 35 years and has owned the store for 25. "I've never seen more changes than in the past three years," he says. "Anybody who makes a living making pictures is particularly vulnerable."

One school of thought in the industry is that the demand for professional processing will come back in a year or two. But will independently owned camera stores survive until that happens– if it does?

"I think it's going to be really hard on small businesses," predicts Stubblefield.

It may be even harder for the newest generation of snap-happy photographers when they encounter a flawed CD or a crashed hard drive. The children of the digital age, says Alter, "may grow up without a visual record of their childhood."

Andrew Rader at Cary's Camera says the good news is a greater percentage of digital photos are being processed now than five years ago– although a lot of those are printed at home.

"We made our money printing, and we had no space to diversify."

"I do sell cameras and accessories, but photo finishing is our bread and butter."

913 West Main

Charlottesville's oldest camera store, the Camera Center, shut its doors on West Main last spring to consolidate operations at Seminole Square. Thanks to the magic of digital cameras, it's seen its film processing drop by 50 percent, a decline that caused Rapid Photos to close its doors in January.

A

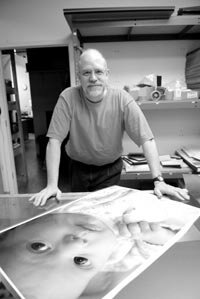

A lot of professional photographers take their film to Stubblefield Photo Lab on Harris Street. John Stubblefield has been in the business for 28 years, and still shoots a lot of slides.

#