New hope: 'Conditional approval' for ALS study

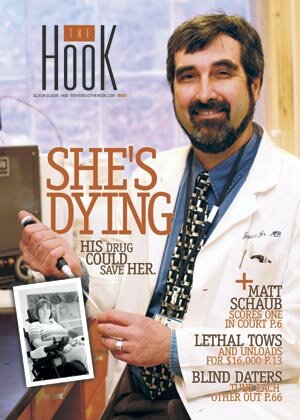

Nearly four months after UVA Health Sciences Center pulled the plug on an intriguing study of a drug to treat Lou Gehrig's disease, the study's ailing volunteers have new hope: neurologist James Bennett now has the University's "conditional approval" to treat 40 patients for six months.

But before he can begin, there's one huge hurdle to leap.

"I need to raise $200,000," says Bennett. The money would fund a full-time coordinator and buy enough of the drug for 40 patients for six months.

For Mary Jane Gentry, the subject of the Hook's February 24 cover story, "She's dying: His drug could save her," the good news is tempered by a ticking clock.

"Time is crucial for anybody with this disease," she says. "We're sitting here waiting for the worst."

Suffering from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Gentry– once the director of a UVA dialysis clinic– is confined to a wheelchair in the Laurels, a nursing home off 29 North.

When doctors diagnosed ALS in August 2003, they told Gentry she had fewer than three years to live– three years in which she would lose the ability to walk, talk, swallow, and eventually to breathe. There is no cure, she learned, and no effective treatment.

As soon as Gentry heard that Bennett was starting a clinical trial for ALS at UVA, she signed on, though she had little hope that it would save her. But after eight weeks receiving just one-third the dose Bennett had hoped to eventually administer, Gentry noticed a startling change: she could suddenly move her left hand, the use of which she had lost several months earlier.

Gentry didn't know it then, but she wasn't the only one experiencing such unprecedented changes.

Richmonder Bev Nicola also noticed improvements in her condition while taking Bennett's drug. The disease had attacked nerves in her mouth and throat, robbing her ability to speak and forcing her to communicate through a voice synthesizer that translates typed text into sound.

After eight weeks on Bennett's drug, pramipexole, a chemical mirror image of a drug already on the market to treat Parkinson's Disease, Nicola could articulate several words.

"My grandson was so excited," she recalls. She also regained enough strength and muscle control to climb stairs and stand on her own.

Nearly half of the study's 15 ALS-afflicted subjects reported positive effects and none reported side effects.

But those "little positive anecdotes," as Bennett calls them, were not enough to sway the Human Investigations Committee, the 22-member ethical board that must approve all human trials conducted at UVA.

"The committee had a lot of concerns about a lack of animal safety information," said Committee chairwoman Karen Schwenzer of the decision to turn down Bennett's request for an extension of his trial. "More extensive animal studies are usually done before the drug reaches people. It's absolutely usual practice."

Schwenzer, who spoke to the Hook several weeks ago but was unavailable to comment for this story, explained that Bennett had given his drug only to mice for eight weeks, and that he'd been approved to test it on humans for eight weeks. Bennett's study, she added, was a "phase I" trial, designed only to look for side effects– not for medical efficacy, which is studied in phases II and III.

"Though it's very exciting to think that there's a drug out there that may help those with ALS," she said, "the paramount mission of the Committee is to protect the safety of the research volunteers."

The study volunteers are baffled by the committee's decision.

"So what if the drug kills me," says Gentry, "the disease is going to anyway. If we can learn from the drug, then at least my life has some impact in its last few years."

Thwarted by the Committee's decision, Bennett turned to the FDA for approval on a "compassionate use" basis, a designation that rushes the approval process for terminally ill patients.

The FDA gave him the go-ahead for compassionate use, and last week the Committee granted him conditional approval.

Bennett isn't arguing– particularly with the Committee's requirement that he hire a study coordinator.

"The [Committee] is very correct about this," Bennett says. "There's a lot of paperwork, and we need someone who is keeping up with it."

Bev Nicola says she's grateful the FDA granted approval and that the Committee is allowing Bennett to proceed, but she wishes the Committee had acted sooner. Since going off the drug, she has once again lost the ability to stand unassisted, go up stairs, and articulate words.

As for Gentry, she has seen the use of her right hand, her "good hand," deteriorate to the point that she can no longer even hold an envelope.

"I think it's sad that they didn't act until their back was to the wall," says Nicola, noting the February 27 death of one of Bennett's original study subjects– the second to die since the study stopped in late November.

While he pursues compassionate use for the current patients, Bennett also hopes to get his formal study back on track. He plans to give mice massive doses of the drug for a year and hopes to run a second phase I safety trial on humans. He'll soon present those plans to the Committee.

Meanwhile, Nicola says she and her husband, Eli, are hard at work raising money to help Bennett fund the study.

"Lou Gehrig died 50 years ago," she says, "and there's still no cure or medicine to slow it down. It's time we all get mad and fight."

#