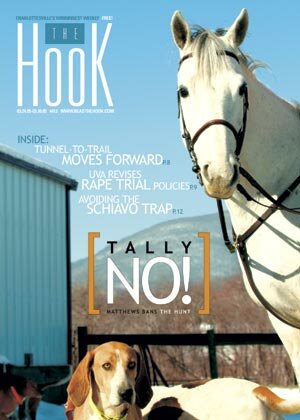

Tally no! Matthews bans the hunt

To many of us, "Fox Hunt" is the name of a new subdivision. Or was that "Fox Run" or "Fox Ridge"? While the allegedly sly mammal helps sell thousands of acres of real estate, very few Americans actually "fox chase" over the countryside.

That's something they do in England. Er– used to do. There will always be an England, but now it will be a kingdom without that particular tradition. After a vote last fall and support from British Prime Minister Tony Blair's government, the British ban on fox hunting took effect February 18.

Could it happen here? Local fox hunters say it's unthinkable that such a time-honored rural ritual– with hounds, horses, and a brass horn– could be in jeopardy.

Yet to packs of animal rights advocates, it's equally unthinkable that chasing an animal with the express aim of tearing it to pieces could be considered sport.

Hunting stateside

"The hounds, they love it," says Bob Satterfield as he waits for the pack to appear. "That's what they're bred for."

These are American fox hounds belonging to Rita Mae Brown. A celebrated novelist who shot to fame after the 1973 publication of Rubyfruit Jungle, Brown has served as master of the Oak Ridge Fox Hunt for over a decade.

In 1993, Brown resurrected Oak Ridge from an earlier club founded in 1887 into one that now counts approximately 50 members. Here, at one of the last hunts of the season, a small group of Oak Ridge stalwarts have gathered for a gallop across the snow-covered fields of her Tea Time Farm in Nelson County.

Brown considers the English ban a wake-up call.

"It reminds us that when city people who know nothing of the country get in the driver's seat, they can do irreparable harm," she says.

She brands Tony Blair's Labour Party "abysmally stupid" and attributes the ban less to humanitarian concerns– its ostensible justification– than to class warfare. Trumping the objections of the House of Lords, the House of Commons outlawed fox hunting in November with a rarely used Parliamentary procedure.

"We don't have any class hate," Brown says of America. "We don't understand that hate."

The biggest difference between hunting here and there? "Well, you don't kill it here," says Brown. "I couldn't kill it if I wanted to. For one thing, they're very sly."

While the red fox, vulpes vulpes, is considered a pest in England (where it's still legal to shoot them), most American hunters say they really just enjoy the thrill of the chase.

"We never get a fox, ever," laughs Gretchen Robb, who has been riding with Brown since 1991. "It's just the hunt and the run and the camaraderie with others."

Robb, the wife of Albemarle Sheriff Ed Robb, says that only one fox has ever been killed at her hunt club. "It was shot because it had distemper," she says. "I certainly wouldn't be hunting if a fox were killed."

Hunters do a lot for the fox that the public is unaware of, Robb and Brown claim, such as putting out heartworm-preventive kibble.

Brown doesn't see here the level of passion– either for or against– that the sport has invoked in England. In September 2002, about 400,000 hunting supporters, including a few from Charlottesville, clogged central London by marching through the streets in one of Britain's largest-ever protests.

"We're such a small sport," says Brown, estimating a total of 15,000 North American fox hunters if Canada's included. "I don't know how interested people are. I think they'd rather hear about steroids in baseball."

But not all hunters follow the call of the mild.

Born again

"I'm a reformed, repentant fox hunter," says Albemarle resident Kay Hooper*, who began hunting when she was five years old. Now 50, she says she had a "horrendous" experience last September when one of the Scotties she raises was chased by a pack of dogs. It took all night for the shivering, traumatized pup to calm down.

"It occurred to me," says Hooper, "that a fox would feel the same way."

Although Hooper is still a member of the Farmington Hunt Club, her former love of the hunt has turned to disdain. She accuses Brown of anthropomorphizing foxes in her novels by portraying them as incredibly smart animals that adore the chase.

"Foxes do not like to be pursued by predators," declares Hooper. "How would you like to be chased by a creature– the hound– more than twice your size who wants to kill and eat you?"

Brown scoffs at the charge of anthropomorphism and points out that the animal's cleverness has been celebrated since Aesop wrote his famous fables. Maybe, Brown jokes, the foxes are "trying to vulpemorphize me."

Hooper jabs at what she calls the hypocrisy of some of her fellow fox hunters, such as the owner of a pet products store who didn't want her name in an article about fox hunting.

And Hooper was particularly appalled that the Farmington club was hunting on Scottsville-area property owned by Dave Matthews. The popular singer is on the Humane Society of America's list of "Animal Friendly Celebrities."

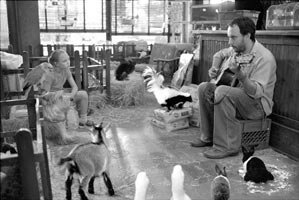

He's certainly friendly in his big-screen debut. Because of Winn-Dixie, a major motion picture released last month, features Matthews as a mysteriously benevolent ex-con who runs a pet shop. In a pivotal scene in the film, the animals have gone berserk after getting out of their cages. Matthews sings a tune to calm them.

Even if Matthews vocally supported fox hunting, he might still be in good standing with the Humane Society.

"Celebrities usually help on a special issue because it's close to their heart," says Michael Markarian, executive VP with the Humane Society of the United States. "They're not obligated to align with us on every issue. They're not under contract."

In early 2002, Matthews bought several Scottsville-area farms previously owned by John Kluge and donated to UVA. The farms– which cost $5.3 million for a total of 1,261 acres– provided a place for the Matthews family to demonstrate environmental and agricultural stewardship. Among the goals: "preserving a diversity of plant and animal species," according to one Matthews website.

"How does one preserve species by allowing hunting of said species?" demands Hooper.

It turns out that Matthews, who spends much of his time in Seattle, has not taken up hunting, and an associate suggests that Matthews was stunned to learn of the hunts.

"Dave Matthews has never allowed fox hunting on his property," says Matthews spokesman John Vlautin. "Any activity of that kind that happened in the past was done so without his knowledge. He has taken steps to ensure that this will not take place on his farm ever again."

So who gave the Farmington Hunt Club permission to hunt on Matthews' land? Farm manager/Matthews lawyer April Fletcher sits on the Farmington Hunt's board of governors, but she declined comment for this article.

Now that the Farmington Hunt has been banned from Matthews' land, the Humane Society hopes other landowners will follow.

"We are against the chasing and killing of animals for sport," says the Humane Society's Markarian, who notes that some states– Colorado, Oregon, Massachusetts, Washington– have banned hunting bears, bobcats, or cougars with dogs. But not foxes.

However, Markarian notes that the British ban has put a spotlight on an otherwise unheralded issue. "Most people in America," says Markarian, "don't know fox hunting occurs here."

Rita Mae Brown says she works with the Humane Society. "They're a worthy organization," she says. "It's an issue on which we disagree."

Brown sees a bigger threat to hunting than the Humane Society or PETA: development.

Each year, Albemarle County's rollicking real estate developers turn undulating green fields into impenetrable subdivisions. Even on larger parcels, some Albemarle arrivistes may not smile on roving bands of horses, hounds, and humanity.

"People coming from New Jersey to pay $750,000 for two acres have a different mentality," says Brown. "They come here because they like our ways and then don't want to join in. It's hard to understand why people would live in this big mausoleum and object to hounds going across their property."

Faulkner's legacy

Seventy-two-year-old Jill Summers grew up with a pack of hounds. Her father, William Faulkner– besides being one of the world's leading authors– was an enthusiastic fox hunter.

Now serving as Master of Foxhounds for the Farmington Hunt, Summers is aware that Parliament's 2004 Hunting Act reverberates across the pond.

While the English ban may stop a few hunters– and even that's doubtful, given compilations of "ways to hunt legally" and reports that many intend to defy the law– Summers foresees other casualties.

"There's a very well organized effort in California to ban all hunting with dogs," she says.

Dogs are at the heart of the Millbrook Hunt diaries, a 20-year chronicle of one New York fox hunting club that detailed numerous incidents of packs of hounds killing foxes, deer– even pet cats and dogs. "It gave us a look at fox hunting, and we realized it's not just a benign ride through the countryside," says the Humane Society's Markarian.

Summers dismisses with a rural pragmatism the idea that hunting is cruel to the fox.

"It's a very quick death," she says. "The fox is dead as soon as the pack gets it." Which, she claims, seldom happens anyway.

"Foxes are so much smarter," she says. "They can go under the earth, climb a tree, or go through a herd of cows. Hounds go by smell, not sight."

She maintains that a fox is killed "only if it's sick, old, wounded, or stupid."

Critics say the stress of the chase itself can be life-threatening. Cambridge University professor Patrick Bateson found that deer suffer stress from being chased by hounds. In a 2002 radio show, he said the evidence was less clear for foxes, "although it can't be very nice for a fox being chased by a dog. But I mean, nonetheless, it may not be so acute as it is in a stag hunt."

The two sides are unlikely to agree anytime soon on how much the fox enjoys the hunt.

Summers predicts that the British ban will have its own fatal fall-out. For starters, English foxes– considered vermin because they sometimes attack livestock– may still be legally poisoned, trapped, beaten, or shot. 'They're going to be killed and die a horrible death," says Summers.

Foxes aren't the only victims. "Thousands of fox hounds are going to be put to death," says Summers. "All they do is hunt. They're not pets. They're pack animals."

Also threatened are the livelihoods of those who support the hunt: blacksmiths, feed suppliers, and those who work in the kennels and barns. An England-like ban would affect "a lot of people in Albemarle County," she says.

And Summers doesn't doubt that the common perception that fox hunting is "a rich man's sport" contributed to its demise in England. "But it's not," she says.

While keeping a horse is notoriously expensive, Summer says the cost of joining a hunt club isn't. Many people who pony up Farmington's $1,000 initiation fee and yearly dues of $1,200 - $1,500 don't even own horses, going on foot instead, she says. And a large number join just for the social interactions.

Summers is in shock about the British ban on hunting. "I still believe one of these days it will come back," she says.

What would her Nobel Prize-winning father have said about England's reform of its ancient tradition?

His only child doesn't hesitate with her answer: "Probably something unprintable."

"Come on children; come on babies," Rita Mae Brown cajoles her American fox hounds. She gets to blow the horn, too.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

A thing of beauty: "It's some of the most gorgeous pageantry," says Rita Mae Brown, who promises that when the hounds "sing," your hair will stand on end.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Attention novices: They're hounds, not dogs.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Gretchen Robb says she wouldn't hunt if Oak Ridge members actually killed healthy foxes.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Master of the Farmington Hunt Jill Summers predicts dire consequences for England's foxes and hounds from the recent ban on hunting.

PHOTO BY CATHY SUMMERS

Was Humane Society hero Dave Matthews outraged to discover fox-hunting on his land?

Meggie was terrorized by a pack of roaming dogs, an incident that turned her owner from avid fox hunter to fox sympathizer.

PHOTO COURTESY KAY HOOPER

#

*EDITOR'S NOTE- Fox hunting foe hides name

Published March 31, 2005, in issue 0413 of the Hook

Regarding last week's cover story about fox hunting ["Tally no: Matthews bans the hunt"], it turns out that the key local critic of the practice was not who she said she was. A woman who identified herself as "Kay Hooper" claimed her pet dog was harassed by a pack of dogs (not foxhounds) and blasted some members of the Farmington Hunt as hypocrites for not speaking publicly about their enjoyment of fox hunting.

After publication of the story, however, the Hook learned that the critic herself had not truly spoken publicly, as she had used a pseudonym when talking to the Hook. A brief investigation reveals that her name is Jane Morley, and according to Master of Foxhounds for the Farmington Hunt, she is a lapsed member of the club.

Morley did not return phone calls from The Hook, but did email a statement again condemning fox hunting.

It is always the Hook's policy to quote people using their real names or to reveal when a pseudonym is being employed (along with the reason).

#