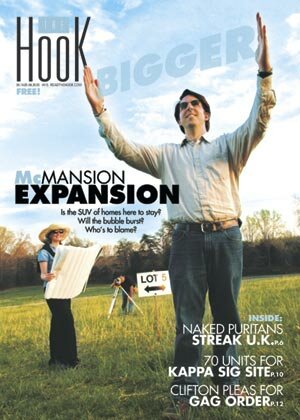

Sky high: Is county government to blame?

At this moment, the number of houses listed for sale in Albemarle County for over $1 million is 63. The number under $150,000? Zero.

The down side to a "best place to live," as any teacher, police officer (or reporter) can attest, is that Albemarle housing is not affordable for anyone earning a typical paycheck. And one school of thought holds that government regulation is to blame.

"I think the question of regulation driving up costs is not even academic," says Neil Williamson of the Free Enterprise Forum. "If it's mandated by a municipality that you must do something, that will increase the cost. The question is whether the public wants to pay for those mandates."

Board of Supervisors Chair Dennis Rooker begs to differ. He pegs supply and demand in an appealing area as the reason median real estate prices have risen 50 percent in the past five years.

"If you're in a very attractive community, the price of housing is more than in those that are not desirable," says Rooker, pointing to Southwest and Southside Virginia as places with plenty of low-priced housing.

Still, many in the building community call Albemarle's high-density, pedestrian-friendly "neighborhood model" a factor in the rising cost– and lack– of affordable housing.

The sidewalks, tree-lined streets, and green spaces now required by the county would have added $34,000 to the cost of a single-family house in "Timberwood," a section of the sprawling Forest Lakes subdivision built in 1997, according to a 2004 study by the Blue Ridge Home Builders Association.

"The question is whether government should mandate infrastructure," says Williamson. "I know neighborhoods that are nice without sidewalks on both sides of the street, where there are no street trees but there are trees in yards."

"I think everyone is concerned about affordable housing," says Dave Phillips, CEO of the Charlottesville Area Association of Realtors. "At the same time, the county passes regulations like the neighborhood model that give builders less flexibility."

The county's Comprehensive Plan was intended to cluster growth in designated areas like North 29 and Crozet. Could the regulations actually be pushing growth into the rural areas? Critics of the Neighborhood Model think so, and their view is supported by some recent statistics.

In 2004, only 53 percent of new home permits issued were in growth areas, down from a high of 70 percent the previous nine years, according to Albemarle planning director Wayne Cilimberg.

"Time is money," says Phillips. "It's easier and cheaper to build in rural areas," he says.

That's a scenario county officials want to fix. "We want to get those numbers much lower in the rural areas," says Cilimberg.

He also points out that Albemarle had high housing prices way before the neighborhood model came into being. "The place is popular," he says.

However, the popularity isn't causing a housing boom. In fact, Cilimberg says, the number of residential permits issued last year– 599– was the lowest since 1995. While he suggests that some projects in the pipeline will soon bolster that number, developers see it as further evidence that building in Albemarle is difficult.

"The problem with the neighborhood model is it's the only model the planning department and planning commission want to see," says Phillips. "But it was intended to be just one model."

"It's not mandatory," counters Supervisor Rooker. "The neighborhood model is only in growth areas." And Rooker argues that such a plan is necessary to accommodate the 1.5 to 2 percent annual growth in Albemarle.

"The goal is to try to protect the rural areas," says Rooker. "If you're going to be successful, you have to make an urban area attractive and make buyers want to live on a quarter-acre lot rather than a three-acre lot."

Clement "Kim" Tingley, who's running for Mitch Van Yahres' 57th District General Assembly seat, owns Tingley Construction, which specializes in affordable housing in the Richmond area. He says regulations there also drive up the cost of housing.

"Sometimes when people are spending money that's not theirs, they lose sight of what's no longer affordable," says Tingley.

Another 57th District candidate, Rich Collins, doesn't necessarily buy the idea that government restrictions on growth increase the cost of housing.

"Based on national surveys, there's no evidence that correlates growth management with housing price increases," says Collins, a founder of Advocates for a Sustainable Albemarle Population. ASAP, as it's called, is dedicated to stopping growth, which critics say inevitably leads to higher housing costs and eradicates affordable housing.

Collins calls attacks on growth management a developers' ploy to imply that any environmental regulations are a cost to be passed through to the buyer.

"Developers say they're the good guys fighting for the buyer," says Collins. "It's disingenuous. The cost of government regulations is one developers take into account when they try to buy land." He contends they're not going to take on the risk of beginning a development unless they know they can make an acceptable profit.

However, Collins concedes that developers could be right about some regulations. In particular, he's concerned about any ordinance that requires more impervious surfaces or fails to naturally process storm water.

"We should never put on costs that cannot be justified by a corresponding public benefit," he says.

Collins, too, is concerned about affordable housing, and he believes housing, as a basic human need, should be treated differently than other commodities, with government making sure that safe and secure housing is available to those who don't make enough to buy in Albemarle.

Mortgage approvals are often calculated on the assumption that a home buyer can afford to pay 30 percent of her salary. That means someone making $35,000 a year could afford a $138,000 house– and that she's pretty much out of luck in Albemarle, where the median sales price was $262,975 in 2004.

Rooker doesn't believe more affordable housing was built before the neighborhood model was approved. And he says the county is taking steps, such as requiring that developers make some concessions to affordable housing in rezonings.

He holds up the Old Trail subdivision currently under construction in Crozet as the neighborhood model ideal, mixing million-dollar mansions with $175,000 townhouses.

The Charlottesville Area Association of Realtors has taken police, teachers, nurses, and firefighters under its wing with its Work Force Housing Plan. Along with the Piedmont Housing Alliance, they've established a fund that helps buy down mortgages for these essential workers. "It's a key program," says Phillips. And it just won a national award.

But what about the grocery clerks, the day care providers, and social workers– not to mention the construction workers who build Albemarle's million-dollar mansions? Are they fated to continue to commute from Fluvanna, Nelson, Louisa, Greene, and Augusta counties to provide Albemarle's services?

Says Rooker, "There's no magic bullet. We live in an attractive area. At the end of the day, market forces determine the price of a house."

Gigantic houses sprout in Albemarle, while mid-level workers flock to surrounding counties for affordable places to live.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#