Ratings game: WMRA claims non-com supremacy

Just 10 years after arriving to grab a bite out of the local market, an upstart Harrisonburg broadcaster has ousted the longtime public radio leader to become Charlottesville's #1 public radio station– for this round of ratings, anyway.

In Arbitron's latest numbers, WMRA was king of the noncommercial hill, pulling in a 7.7 share. That tops Roanoke-based rival WVTF, which pulled a 6.4 share of Charlottesville-area listeners in the "12-plus" category: listeners 12 or over from 6am to midnight during an average quarter hour (AQH).

"Our AQH share is pretty impressive," says WMRA general manager Tom DuVal. "A 7.7 share– that's the number commercial stations use to sell advertising."

DuVal, who came to WMRA about a year after it charged into Charlottesville in 1995, calls the ratings "phenomenal" for a non-commercial station. "It's pretty much unheard of in public radio."

Indeed, in the Arbitron commercial 12 pluses, only "Lite Rock" Z-95 has a higher rating, with an 11.5 share.

Others are not quite so giddy about WMRA's numbers. "This is the first time I remember they topped us in share," says Glenn Gleixner, head of WVTF. "We topped them in cume ratings."

Cume is the estimated actual number of the 12-and-older population in the Charlottesville metro area tuning in: 22,000 for WMRA; 25,300 for WVTF.

It's long been a mystery to some how a town the size of Charlottesville ended up with five public radio stations– the same as New York City.

Odder still, although Charlottesville consistently ranks as one of the top National Public Radio-listening towns in the country, it doesn't really have its own NPR station. The "Morning Edition" crowd must choose between WVTF and WRMA– and most recently RadioIQ.

Public radio's version of talk radio, featuring BBC news and NPR talk programs, RadioIQ is a WVTF project. Gleixner says the fledgling station– locally broadcast on 89.7 FM– tallied a 2.2 share in its first ratings in spring 2004, falling to 1.3 in the most recent fall 2004 ratings.

"I wouldn't make too much out of these ratings," says Gleixner. "What public radio really considers is listener response. We do very well with people who support us."

WNRN founder Mike Friend is dubious about WMRA's ratings– and the need for two NPR stations. "I don't know why WMRA has those numbers because nobody listens to them. Who's going to listen to WMRA fade out when you can listen to local station WVTF?"

Friend tells a story about a car dealership that was keeping track of the radio presets on cars coming in to determine where to spend its ad dollars. "WVTF was on most radios," he says. "We were number three."

Friend also scorns the value of 12-plus ratings. "It's your demographics that count," he explains. "You don't buy 12 plus if you're selling Volvos."

Hour of day also is a consideration. Friend says his afternoon show does best with 18-to-34-year-olds. In the last ratings, he says, WNRN tied with 3WV with a 9.4 share of the males in the 25-to-44 market.

Not surprisingly, Friend doesn't put too much stock in Arbitron ratings to begin with– but notes that WNRN consistently pulls in a 4 or 5 share. "In Arbitron, you have to have five books filled out for your station to show up at all," he says, referring to the daily logs designated listeners keep.

DuVal also acknowledges the whimsicality of Arbitron ratings, which depend on where the diaries are placed and whether those places pick up a given signal. "You're really extrapolating from a small number of data points," he says.

Nonetheless, he's pleased with WMRA's top spot. "We typically do better in Charlottesville," he says. "There are more public radio-type people than in Harrisonburg."

So why doesn't Charlottesville have its own NPR station? Former UVA dean– and founding director of NPR– Bernard Mayes suggests an answer.

Essentially, UVA station WTJU's board voted in the late 1980s or early 1990s to remain a college radio station.

"To become a full-fledged public radio station was not in its best interest," explains Mayes, who admits he was disappointed by the decision at the time. "It was better for [WTJU] to have its own identity. You may find the student audience not well served by NPR."

"Why duplicate programming?" asks Chuck Taylor, WTJU's general manager.

He says WTJU doesn't really pay much attention to ratings and isn't bothered by its 2.5 share. "We're not trying to be number one. We try to fill in for those who don't have a place to go."

Taylor points out another problem with Arbitron. "They do not sample non-stable populations like 22904, which is the university area. It's probably detrimental to any station with student listenership."

Taylor thinks the diversity of radio– both commercial and noncommercial– bodes well for Charlottesville– "as long as we're all getting financially supported– and we are," he adds.

The ratings game

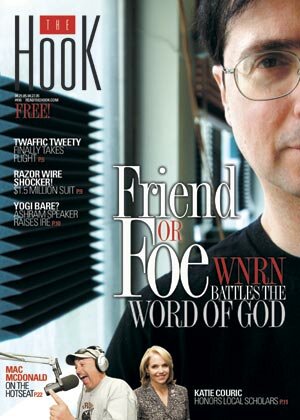

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#