Friend or foe?: WNRN battles the word of God

PHOTOS BY JEN FARIELLO

Why have some WNRN broadcasts been coming out of just the left side of your car stereo?

A notice on the local radio station's website has the answer: 91.9 WNRN in Charlottesville has been engaged in a heated battle with DC's 91.9 WGTS for the same space on the radio spectrum. Mono broadcasts, it turns out, are more resistant to interference from rival stations.

"This is an explanation for people who wake up one morning in Crozet expecting to hear Acoustic Sunrise and instead hear some blissed-out moron singing about Jesus," says WNRN's protagonist and antagonist Mike Friend.

In case you haven't already figured this out, WGTS has a bit of a religious bent. Friend isn't so sure that's just an incidental detail.

"Because they are a religious organization and have their hooks in all sorts of right-wing political groups, they think that they'll be able to get away with this," claims Friend.

What they're trying to get away with, he says, is a filing that's in flagrant violation of FCC code. So Friend did a little filing of his own.

"It's your right and your ability to become my perfect enemy. I'll walk away and say you f***ing disappoint me... Passive-aggressive bulls**t." –"Passive" by A Perfect Circle on WNRN's Boom Box show at 9:11pm April 15.

"Jesus is the answer for the world today. Above him there's no other– Jesus is the way." – "Jesus is the Answer" by Michael W. Smith on WGTS at 9:27pm April 17.

Although WNRN and WGTS operate on the same frequency, what we have here is a failure to communicate– or at least to work out a compromise.

Founded by Friend in the summer of 1996, WNRN may offer a low-power signal, but some of its programming is clearly high octane. While the majority of the station's programming is "modern rock," its nighttime "Boom Box," an installment of hip-hop and gangsta rap, holds nothing back– certainly not the four-letter words.

Like WNRN, WGTS is also non-commercial and accepts business "underwriting." But there the similarities end.

WGTS bills itself as "family friendly– no blue humor, no foul-mouthed DJs, no offensive lyrics." While WNRN includes local news plus "The Daily Feed," a national news satire, WGTS sticks pretty close to the Good News. Family-friendly music fills much of the daily airtime. Syndicated features include "Voice of Prophecy," "Family Minute with James Dobson," and "Laugh Your Way To A Better Marriage."

A map at WGTS.org shows that the station's coverage should reach Gordonsville, Orange, and Madison (with Charlottesville off the map). Such coverage was made possible when WGTS took its new antenna online in March 2004– when the interference with WNRN began.

Ordinarily, one wouldn't expect a problem because both stations are in compliance with FCC regulations governing geographic spacing between broadcasters using the same frequency– regulations designed specifically to prevent situations like this.

Scott Steward, who handles public relations for WGTS, says that since the broadcasting towers are 100 miles apart, the coverage areas are separated by a good 70 miles.

"If I'm listening to a low-wattage station outside its primary coverage area, there might be some interference," he says. "Any conflict is probably coming in secondary or tertiary coverage areas."

By "low wattage," Steward means WNRN's broadcast power of 325 watts, which is periodically getting trounced by WGTS's 23,500 watts. No wonder there's interference, right?

Wrong.

"Radio engineers learned a long time ago that you do a lot better with height than with power," says Friend. WNRN's broadcast altitude of 1700 feet above sea level has made possible its expansion into the Lynchburg market, 50 miles south. (As home to Jerry Falwell's Liberty University, that's probably a market WGTS would covet.)

Max Hoecker, personality on "The Big Greasy Breakfast" morning show agrees with Friend's assessment: "If we pop off the air, a station from North Carolina takes over our frequency." And Hoecker's talking about WWWV, a powerful Charlottesville broadcaster.

But WNRN doesn't have to go off the air to be disrupted.

So why is WNRN getting walloped despite the super-tall antenna and what the FCC considers adequate geographic isolation?

Friend blames a rare atmospheric phenomenon called "tropospheric enhancement"– somewhat unique to this part of the country– in which stacked air masses called "inversion layers" can enhance VHF signals such as FM radio broadcasts.

"The FCC is kind of acting like the Roman Catholic Church did when people said the earth was round," says Friend, zinging another barb in the direction of his foe. "They didn't foresee it; therefore, it doesn't exist."

Steward isn't terribly sympathetic over the bumping of signals. "The FCC can't build a wall" around the towers, he says.

Friend hopes that WGTS will no longer even have the right to broadcast at 91.9 at all, let alone do so in a manner that thrashes WNRN's signal.

What happened is that WGTS submitted appropriate license application paperwork before its license was set to expire on February 9, 2004, but neglected to designate itself as a noncommercial station.

"The only difference is that for a commercial application you have to pay a fee," says Don Martin, attorney for WGTS. "The FCC told us that one way to correct the application would be to re-file it, which we did the next day. Another way to make that application valid is to just pay the fee, and we did that too."

So the station is a noncommercial station fulfilling all the requirements for a commercial permit.

Nice try. As state senator Emmett Hanger learned the hard way last week, some government agencies mean business with deadlines. Hanger had been seeking a nomination for Lieutenant Governor, but traffic accidents on I-95 and I-64 delayed the April 15 arrival of campaign volunteers carrying ballot-access petitions to the State Board of Elections in Richmond. Even though the campaign reportedly missed the deadline by only half a minute or so, the Valley Republican's campaign was over.

WNRN had been eagerly waiting for a chance to expand its coverage area and jumped in with a timely– and correctly filed– license application with the FCC to increase its broadcast power.

Martin believes his station's file was proper. "If you file an application that requires a fee, you have a certain amount of time to pay that fee and maintain the validity of the filing," he says. "The fee was paid within that period of time."

Martin supplied the Hook with an FCC website for electronic filing of applications which does indeed support his claim– it appears that WGTS had a 10-day window during which to pay the $120 license application fee and keep the initial application valid.

That tactic really gets Friend steamed. "If they wanted to call this a commercial application, then fine. We'll use commercial rules," he fumes. "Under commercial rules, the spacing between the stations wouldn't be permitted.

"It's ridiculous," Friend continues. "It's a noncommercial frequency, for Christ's sake."

Initially, everything below 92.1 was reserved for the supposedly "educational" broadcasters, says Friend. But the FCC seems to have let that plan disintegrate. These days, most broadcasters in the noncommercial band are religious stations.

Still, the ever-quotable Friend doesn't seem to be too annoyed with the FCC. "If someone has cockroaches all over their home, it's not the fault of the cockroaches," he says.

Friend also points to a specific clause in the relevant FCC code– a specific word in a specific clause, rather– that suggests that WGTS might be out of luck despite its quick-draw checkbooks. The paragraph states that license applications and modification/construction projects (in this case, for erection of a new antenna) must be completed by the deadline.

WGTS, he says, is treating this requirement as an "or" clause. Because a new antenna was not ready for use until March, they were using an older one. Martin claims that incidental details of implementation can be changed without notifying the FCC, a notion which Friend and WNRN's attorney find preposterous.

At this point, there's nothing to do but sit back, wait, and let the FCC decide. For the time being, there are two fundamentally incompatible applications on file with the Commission, an indeterminate number of befuddled listeners, and at least one ticked-off station manager. (John Konrad of WGTS did not respond to a request for comment.)

"Barging headlong as it does into the legitimately authorized facilities of WGTS, [WNRN]'s application is out of place and in flagrant violation of the Commission's rules for protecting co- and adjacent-channel stations," reads one of the WGTS pleadings on file with the FCC– to which a related WNRN pleading retorts, "The Commission should not permit licensees to engage in such gamesmanship in order to circumvent its Rules."

"Since this is a contested proceeding, where both sides have made filings, we're not allowed to have any substantive discussions with FCC staff, so there's not much that we know at this point," says WNRN attorney Jim Blitz. In other words, there's nothing to do but wait for the possibly exasperating bureaucratic machinery of the FCC to do its work, and hope for the best.

With no further recourse, Friend and Blitz took a page from the WGTS playbook– they decided to appeal to a higher power.

"We wanted to see what the FCC was doing, and we didn't get a good answer. We didn't get any answer, actually," says Rawley Vaughn, former legislative director at congressman Virgil Goode's office. "They sent us almost a form letter saying that they couldn't comment on a case that was still being decided. That makes sense from their point of view, but you would think that if a congressman were asking, they'd pay a little more attention.

"The federal bureaucracy reared its ugly head and said, 'We don't care if you're a congressman.' That aggravated me," Vaughn says. "The more you get involved with government, the more you realize that bureaucracy is crazy.

"The congressman did what he could do," Vaughn sighs. "He's not an FCC judge, and it's improper for him to try to influence the decision."

For the most part, Vaughan was the one handling WNRN's case at Goode's office, but he has since moved on, and the matter has been passed to legislative correspondent Kelly Simpson.

"If WNRN wants to make another inquiry with us, I'm sure Mr. Goode would be happy to consider it," he says.

With or without Goode's help, the battle could conceivably drag on for quite a while. "There are procedures within the FCC for appealing," says Blitz. "It's premature to say what we would do in the event that we lose, but those procedures do exist."

"We have them dead in the water," insists Friend. "The problem is that we may have to wait 10 years to get it heard. There's no way that they could possibly construe what WGTS did as legal. They can't exactly turn down our application, which was timely and legal," he says.

Steward is just as confident: "WGTS has been in full compliance with FCC regulations. It's all a matter of public record."

Martin acknowledges that there are possible solutions that might resolve the situation appropriately for both sides, but he leaves the technical trickery to the engineers. Friend claims that WGTS has so far been unwilling to entertain the idea of a compromise.

"There are compromise solutions that are possible here that would involve them installing a directional antenna or dropping power, but these are not rational people," charges Friend. "They don't compromise. They are very happy. They have displaced the devil's music with the word of God, and that's what they were put on this earth to do."

And so, in the end, WNRN must compromise its own broadcasts instead. From time to time, WNRN lapses into mono, and in some areas is hitting the airwaves at 88.1 with a lower power broadcast.

"A weak signal is better than a strong signal that's interfered," says Friend. "91.9 is effectively a poisoned frequency now."

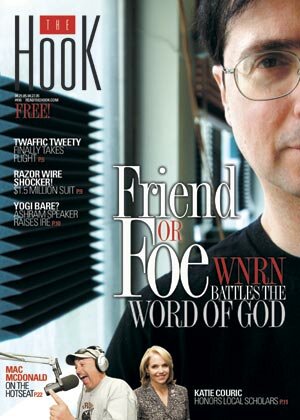

Mike Friend

Mike Friend on the air.

#