Minimum security: Alston shipped to Botetourt

Andrew Alston's family hoped he'd do his time at the Albemarle-Charlottesville Regional Jail– and for a while last spring, the father of the man he killed was afraid Alston would.

"What little time he got should be in a penitentiary," said Howard Sisk, whose only son Walker died at Alston's hands. "He's living at Club Med on Avon."

That was in March, when Alston was still at the Regional Jail after being convicted of voluntary manslaughter in November and formally sentenced to three years, including time served, in February.

On April 29, he was moved to Troutville at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Unless a soon-to-be-filed appeal shortens the remainder of his three-year sentence, Botetourt Correctional Center will be Alston's home until next summer.

Alston, 23, has been in jail since November 8, 2003, the night he killed 22-year-old Walker Sisk on the Corner. He now finds himself in what the Department of Corrections terms a "Level 1-high" facility, almost the lowest security in DOC's six-level tier.

"It's a secure facility," says a DOC spokesperson, who asks that her name not be used. (The usual spokesperson, Larry Traylor, was not in the office.)

Built in 1960, Botetourt can hold 342 inmates, but its mid-July population was 223. The jail is a substance abuse therapeutic community, and Alston likely is in a treatment program, according to the DOC. Alston had been drinking heavily the night he stabbed Sisk 18 times.

Some inmates at Botetourt Correctional have pets through the Pen Pals program. Prisoners can adopt a pet and train it for six weeks.

"It helps inmates with being responsible for something," says the Department spokeswoman. The animal sleeps with the inmate, is groomed and fed by the inmate, and after six weeks is put up for adoption by the SPCA.

"He's living the good life," says Howard Sisk. "We're still devastated. I have a dead child. This does not go away."

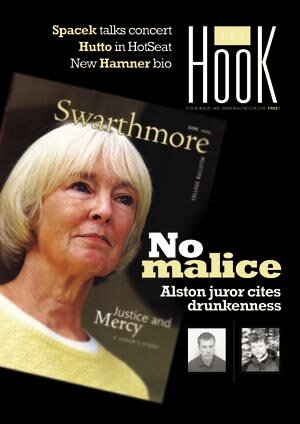

The low-level prison is just another insult for Sisk, still in disbelief that despite the 18 stab wounds plunged into his unarmed son, a Charlottesville jury convicted the UVA student of voluntary manslaughter rather than second-degree murder, which the prosecution had sought, and sentenced him to three years.

"That's what hurt the most," says Sisk, "the jury saying [Alston's] troubled. And seeing people getting eight or nine years for drugs. Is there any justice?"

Off Interstate 81 on the northern outskirts of Roanoke, Botetourt is less than a six-hour drive for Alston's parents, who live in Lower Gwynedd, Pennsylvania, where his father is a town supervisor and attorney, and his mother a school counselor.

Alston's father has a history of traveling to Virginia when his son is in trouble. After his son was charged with assaulting his girlfriend, Robert Alston made a same-day visit to draft an affidavit for her to sign claiming she concocted the story. Testimony in the murder trial indicated that the elder Alston was on the road to Charlottesville again on November 8– at least an hour before his son was arrested. He did not return a phone call from the Hook.

Alston's attorney, John Zwerling, declines to comment on the parents or the facility to which his client was remanded.

"I just want to let the citizens of Charlottesville get on with their lives," says Zwerling. "There must be other things of importance going on there."

Scenic Troutville in Botetourt County is Andrew Alston's home until he's freed June 21, 2006.

PHOTO COURTESY DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS

#