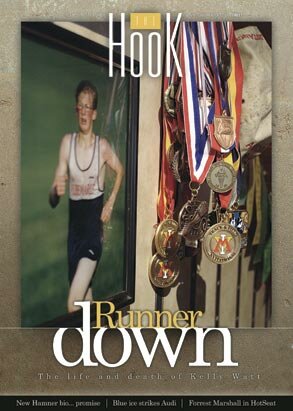

Runner down: The life and death of Kelly Watt

PHOTOS BY JEN FARIELLO

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.

–To an Athlete Dying Young by A. E. Housman (1859-1936)

Tuesday afternoon

Paul Watt was heading to northern Virginia on the afternoon of Tuesday, July 26 for his job selling websites for lawyers. He planned to visit several D. C. area firms and had just registered at his hotel when he got a telephone call from his wife. Their son Kelly, a hard-charging runner and budding journalist, hadn't returned from his daily run. He'd missed dinner and hadn't called.

"That doesn't sound good," Watt thought, as he began dialing his son and heading back to Charlottesville.

What started as a missing person case turned out to be a medical emergency that stunned a community and ultimately robbed it of a distinctive young man whose iron will and love of sports may ultimately have cost him his life.

What is heat stroke?

While many physicians define heat stroke as body temperature above 105 degrees Fahrenheit lasting longer than 30 minutes, confusion persists. There are various diagnoses and various names for heat-related illnesses: heat stress, heat exhaustion, and the worst, heat stroke.

According to the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, no state keeps records on heat-related deaths. However, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that about 380 Americans die annually from heat-related illness. Most of the victims are very old, very young, or very infirm. Kelly Watt was none of these.

The 18-year-old athlete and 2005 Albemarle High School graduate was one of the rare victims of exertional heat stroke, a disorder caused by excercise that overwhelms the body's natural ability to cool itself. And Kelly knew something about the danger. During a sophomore year race in Williamsburg, he had collapsed in sight of the finish line. "His lips were gray; he wasn't making sense," says his mother, Paige Watt, "but he survived."

More recently, Kelly discussed heat's deadly potential in the final installment of "Sports Wrap," his weekly column in The Hook. He opened his July 28 article with a sympathic look at the case of Emanuel Sanchez, a 22-year-old jockey who died July 23, the day after collapsing after a race at Colonial Downs. But by the time the column was published, Watt himself was lying unconsious in the intensive care unit at UVA hospital.

A simple plan

Kelly Watt's bedroom could be mistaken for a young boy's retreat– no posters of rock bands, no lava light, no pin-ups of supermodels. Instead, the room is filled with sports memorabilia.

Color photos of baseball stadiums cover one wall, a stack of pillows shaped like sport balls clusters at the foot of his bed, and the back of the door is plastered with hats of every pro baseball team. As Albemarle High athletic director Deb Tyson put it in her funeral eulogy, Kelly Watt was a straight-forward young man.

"In fact, he wasn't a complicated person," said Tyson. "He had two passions: one was journalism, and the other was running."

Growing up in Chicago, Kelly became a Cubs fan. After the family moved to Indianapolis, he began following the Indianapolis Indians, whose star was Pete Rose's son, P.J. In the stands, Kelly would keep track of the action with a play-by-play scorebook. "He knew everybody's batting average," says his mother.

Kelly's interests eventually coalesced. By the time the family moved to Albemarle in June 2000, he had already begun his journalism career. At the tender age of 12, he created Sports Weekly, a digest with the motto "Concise sports news that keeps you reading." Family and friends snapped up the 10 cents-per-issue publication featuring crayon illustrations.

By 2003, he was so busy writing for the Albemarle High School newspaper and for milestat.com, a statistics-heavy site for Virginia runners, that he let go of Sports Weekly. But he never let go of sports.

Kelly routinely went all-district and all-region in cross-country and track. He made the state cross-country team as a freshman and was named the Central Virginia Runner of the Year. In a weekly coaches' poll– covering 16 high schools including perennial powerhouses Woodberry Forest and Fork Union Military Academy– he held the top spot for his entire junior year.

In his senior year came what some friends and family consider the ultimate prize, the one that honors the top athlete from all Albemarle High Patriot sports: "Pursuing Victory with Honor Award."

Not timid

"I remember him as a freshman walking into a very intense group of juniors and seniors," recalls Lance Weisend, who coached Kelly all four years at Albemarle. "He took some abuse, but he was really stoic."

Over the years, Weisand watched a young man whom no one saw as a "natural" transform himself into an award winner through sheer determination and hard work.

"He was a blue-collar runner," says Weisand of the 5'9", 145-pound athlete. "He always did his job. His stats weren't always the best, but he was always in the mix and dictating pace, and I think that's why the William & Mary coach recruited him."

"He was a risk-taker," says Alex Gibby, the coach at the College of William & Mary, where Kelly planned to register later this month.

The head of what's arguably the state's top running program, Gibby recalls being impressed by Kelly's mettle at the 2004 AAA state meet in Newport News. Running in second place with just two laps to go, Kelly had pushed too hard and suddenly slowed. "He really laid it on the line," says Gibby. "Even though he ran into a little trouble at the end, he wasn't going to be timid."

'I'm not a quitter'

Ridge Road lies 10 or 15 minutes west of town off Garth Road. A classic Albemarle scene, its verdant fields on rolling hills offer residents dramatic views of the Blue Ridge. And for runners, Ridge Road offers something rare in Albemarle County: an eight-mile run without many steep grades or cars. But solitude can prove deadly.

"We figure we're 18,19 years old, and we're in relatively good shape," says Kelly's best friend, George Heeschen. "We don't think anything of running alone or running in the heat."

Heeschen had completed the run on Ridge Road about 30 minutes before Kelly began his, and he says he found the heat "suffocating." Moreover, knowing Kelly's personality, he believes Kelly also completed the full eight-miles that day.

"This year he took calculus against everyone's advice. He just bombed it left and right. I told him mid-semester, after he'd already gotten into William & Mary, 'It's senior year. Just drop it.' But he said, 'I'm not a quitter.'"

Even though he was a risk taker during a race, Heeschen says, Kelly took no chances with dehydration, and a red one-liter Nalgene water bottle was a fixture in his hands. "It was kind of his trademark," says Heeschen. "He'd be filling it up between classes."

The bottle, which he'd won in a race, was found empty on top of Kelly's car on Ridge Road.

Body cooling

"Excercise generates a lot of heat that has to be dissipated," says UVA excercise physiologist Glenn Gaesser. At lower temperatures, heat moves from the skin into the air by simple radiation. During excercise, Gaesser says, the body assists the radiation process by directing extra blood to the skin.

"It's like a car," he says. "You can think of our muscles as the engine and our skin as the radiator. We're sending hot blood out to the skin." Air passing over the skin is like a car's radiator fan.

But radiation won't suffice during hot weather or intense excercise. That's where perspiration comes in.

Anyone who has touched rubbing alcohol has felt the amazing physical power of an evaporating liquid to pull heat from the body.

For every 1.7 milliliters of sweat that evaporates on the surface of the skin, the body loses one kilocalorie of heat. And someone exercising in hot weather needs to lose heat.

Trouble starts when the air is particularly hot and humid, the potentially deadly combination described by television forecasters as the "heat index." Gaesser urges extreme caution for exercisers when the heat index exceeds 90 and explains how disaster can strike when it hits 100.

"If the air temperature is approaching the skin temperature," Gaesser explains, "your ability to dissipate heat through radiation is almost nil."

High humidity has the same effect. When the air is already saturated with water, sweat becomes useless. "No evaporation can take place," he says. But the body doesn't stop trying.

Under the severe combination of high temperatures and high humidity, the human body continues to pour out sweat. Unfortunately, most of it may be wasted.

"The sweat that drips off you is totally ineffective," says Gaesser. "It's only the sweat that evaporates that cools you."

As such inefficient sweating continues, it consumes one of the body's most precious resources: water. Another factor for serious athletes, Gaesser says, is that excercise on consecutive days can create a water deficit of which the athlete may be unaware.

"You can easily lose one to two liters per hour exercising," Gaesser says. "Just envision a two-liter bottle. During a workout, you could lose a couple of those."

'Straight out of the 1950s'

William & Mary's Gibby recalls Kelly's official visit to Williamburg in October. One of the freshman runners was telling the recruit he had never dreamed that running for a college team would be so hard.

"Honestly," Gibby says Kelly replied, "I don't think you'd want it any other way." Already impressed with Kelly's running, the coach found himself impressed with his character. "To understand concepts about hard work that I teach in the locker room is very rare in such a young man," Gibby says.

"He was straight out of the 1950s," says his friend Heeschen. "He just had this aura about him. He was clean-cut, optimistic, and looked for the good in people."

His foible, friends say, was a slight tardiness habit. "Whenever we went out," says girlfriend Rebecca Lehman, "he'd say, 'I'll pick you up at seven o'clock,' but I knew I'd have until 7:30 to get ready."

Even before he captained the cross-country team and racked up shelves of running prizes, Kelly managed to cut a distinctive path through Albemarle High School. Carrying a briefcase has a way of doing that. And in a sea of Beatlesesque mops, what Kelly's friends branded his "comb-over" (actually just a meticulous part in his short blond hair) also set him apart.

On "spirit day" in junior year, students were encouraged to dress as their "twin." Heeschen donned a pair of wire-rimmed glasses and tucked his shirt into a crisp pair of khaki shorts. "Everyone," he says, "could tell I was Kelly Watt."

Matthew Haas has been the principal of AHS for just a year, but Kelly was big on his radar. "Kelly was one of the first students I met," he says. "He came to interview me for the school newspaper, and over the course of the year he would show up on our school broadcast."

Haas recalls that on one of the weekly comic routines broadcast on televisions throughout the school, Kelly was called in to cure a fictional power failure– by running on a treadmill to generate electricity. The other players in the skit yelled at him for not running fast enough. "He was the perfect straight man," says Haas.

Kelly's optimism about human nature resulted in one of the few ugly incidents at his final summer job. It happened at Clean Machine car wash just a week or two before his accident as he was drying off a car. Unmistakable evidence indicated that it belonged to an avid fan of the St. Louis Cardinals. Kelly, still rooting for the rival Chicago team, wisecracked, "Go Cubs."

The customer took back his gratuity and angrily berated the Cubs.

"That caught him pretty off-guard," says Heeschen. "He thought you could joke with anybody. He had a portrait of the world painted in his mind, and he thought there was good in everybody, and that's a pretty mature attitude for an 18-year-old."

Heeschen got a glimpse of that maturity nearly two years ago.

"You're running like a Kenyan– you're running like a Kenyan," Paul Watt was shouting as encouragement to Kelly at an invitational race at William & Mary during his junior year. At the start of the race, Heeschen had inadvertently stepped on Kelly's heel, pulling his shoe off. Despite his dad's cheering, Kelly didn't finish so well. But in typical fashion, there were no complaints or recriminations.

"That was a big race for him," says Heeschen. "There were a lot of college coaches there, and he could have run much faster with two shoes."

A hot day dawning

Under his William & Mary training regimen, Tuesdays and Fridays were days for "hard" workouts, and Tuesday, July 26 dawned hard. Monday's high had been 96, and according to weatherunderground.com, the temperature on Tuesday hit 80 by 9am.

Kelly was an early riser. He'd typically get up at 5:30am in order to run before work. But this was his day off from the car wash. He planned to run in the afternoon.

By noon, the temperature passed 90. At the time of his run, the sun was shining, the temperature was 94, and the relative humidity was 47 percent.

According to an online calculator provided by the National Weather Service, that combination equals a heat index of 101, and some weather calculators suggest adding another 15 degrees for full sunshine. In other words, the heat may have felt like 116 degrees.

Kelly was late leaving the house with his younger sister, Morgan, for dual dental appointments because one of the two family dogs balked at going outside into the summer heat.

Kelly told his mother he was going running at Panorama Farm. "He said he'd by home by 6:30," says his father. "He never missed dinner."

Around 7:20, his mother called Panorama Farm, but he wasn't there. Up in Northern Virginia, his father was calling Kelly's mobile phone. In the hope that his son was simply avoiding a parental call, Paul says he was hitting redial– "about 1,000 times."

"I had this bad vibe," says his father. "I don't know why." As he was packing his bags to head home, Paul got another call from Paige, asking whether to report Kelly missing. "I said, 'Yeah, call the police.'"

A sad day unfolding

Brain damage and delirium are two frequent consequences of severe heat injury, and some of Kelly's friends have speculated that he became delerious as he reached the car.

His water bottle was found empty with both the lid and retainer pulled off– as if Kelly had been frantic to get a drink. His hands were covered in a light-colored dust, as if he'd fallen to the dry gravel road. His car was unlocked and unopened.

"Maybe he couldn't find the door latch," says his father, who eventually retrieved the vehicle. "The whole left-hand side was a pitter-patter of handmarks with dust."

"The reason he was having a delirium is that his brain cells were breaking down," says John Hong, a doctor who, like Kelly, has been writing a weekly column for The Hook.

"Most people don't make it to the emergency room," Hong says, adding that for catastrophic damage to be averted, "You have to cool the body down within 30 minutes."

Kelly's parents believe their son probably started running around 4:15. And like many of Kelly's friends, they believe he finished the entire eight-mile round-trip on Ridge Road. If the run took an hour, he would have returned to his car around 5:15. But he was not found for over three hours.

Compounding the potential for disaster were the facts that Kelly went running alone, and that, by the time he lost consciousness, he'd made himself invisible. His father says police told him his son was found about a dozen feet off the road inside a wild bramble. He had many scratches on his torso as if, in a desperate search to get cool, he simply dove into whatever shade he could find.

A father's return

"I got a call at 8:30 saying they found the car but not him," says Paul Watt. Five minutes later, police had found Kelly and informed his dad that he had an irregular heartbeat. "It sounded worrisome," says his father, "but not that bad."

Kelly was so deep in the brush that he might have remained hidden longer had it not been for one protruding foot. He was transported to the nearby Foxfield race course where the Pegasus medical helicopter touched down to rush him to UVA hospital.

Paul Watt reached Charlottesville as the copter was landing at the medical center. "It's a sinking feeling to see your son coming off a helicopter surrounded by ice," he says.

As the night wore on, the prognosis became more ominous. A hospital chaplain and a social worker soon appeared to speak with the Watts. Then a doctor came in. "He starts saying, 'We've got some real concerns here.' You could see it in the guy's eyes," Paul Watt recalls.

After midnight, Kelly was moved from the emergency room to intensive care. At 4am, the family was advised to prepare relatives for the worst: that Kelly– like most heat stroke victims untreated for more than two hours– would not survive.

Dr. Koenig

"I tend to be an optimist," says Steve Koenig, the critical care doctor who came to supervise Kelly's treatment. "I really thought that there were positive signs."

But Koenig also saw failing organs. And for every organ that stops working, Koenig says, the chance of mortality increases by 20 percent.

"He was really sick when he arrived," the doctor says. "He had evidence of multi-organ dysfunction and low blood pressure. Most people didn't think he'd make it."

One study of survivors from the infamous 1995 Chicago heat wave found that 76 percent of the heat stroke survivors suffered some form of permanent brain damage. On the other hand, most of the Chicago victims were elderly and infirm, two things that Kelly Watt was not. Koenig says that two CT scans and an EEG revealed no obvious brain damage.

Koenig's optimism endeared him to the Watts, but Kelly had sustained horrific injuries, including an all-body form of internal bleeding brought on by failure of his liver and bone marrow. "Early on," says Koenig, "I was encouraged. We were able to control the bleeding."

Like severe sepsis, heat stroke kills cells throughout the body, and as the cells die, they give off poisons called cytokines. Koenig says that Kelly's organs, already injured by the heat, were undergoing further damage from the cytokines. Kelly was put on dialysis when his kidneys stopped working.

That his lungs continued to function while so many other organs were failing seemed to make perfect sense. "As a runner," says his father, "he depends on his lungs."

In the hospital

By Wednesday morning, waves of friends began arriving at the hospital. "It was just a roller-coaster," says George Heeschen. "He'd have great signs of improvement, and other days they'd have horrible news."

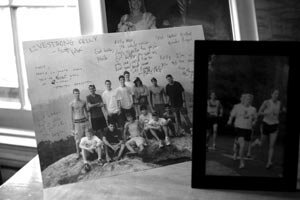

Friends brought a Lance Armstrong Foundation "Livestrong" bracelet but weren't allowed to put it on Kelly. They brought his parents a photograph of the cross-country team perched atop Old Rag Mountain– signed by each young man with hopeful expressions for their friend.

"We had a huge line of people trying to get in there," says Heeschen. "That was really difficult because you don't imagine seeing an 18-year-old in the position he was in. He was pretty beat up. There were scars from all the bleeding and all kinds of tubes and machines on him."

Saturday morning

By the morning of Saturday, July 30, Paul Watt was feeling encouraged enough to break away for a cup of coffee and a brief check on at the family's house on the eastern side of the county near Stony Point. A few minutes from home, Watt got an urgent call from a doctor to come back immediately. "Do I have time to pick up my daughter?" Watt asked. He was told to hurry.

Watt returned to the hospital with his daughter. "For the next two hours," he says, "it was like a scene from ER."

Kelly's lungs had filled with fluid and couldn't process oxygen, and his heart stopped. After a round of CPR, his heart began to beat, but his lungs filled again, and his blood pressure dropped. "The doctor just looked at us and said, 'It's not going to work,'" Watt recalls. The time was 11:48am.

"The bottom line," says Koenig, "is that too much tissue was damaged, and those poisons continued to be produced by the damaged tissues."

Principal understanding

Matthew Haas was working in his yard on Saturday when he got the call on his mobile phone. He quickly called a top administrator and the head custodian to open up Albemarle High School and provide grieving students with a sanctuary.

"My main concern was I wanted to protect Kelly's parents over at the hospital– and I didn't think it was a healthy place for the students," he says.

Someone rounded up refreshments. A youth minister agreed to talk. And Steven Koenig, the doctor who had supervised Kelly's care, came to explain to the gathering teens what had happened.

Risky business?

A member of the clergy at Christ Church wondered aloud during the August 3 funeral whether– in addition to dying tragically– Kelly might have died "perhaps even foolishly." Even before that, his decision to run alone in the heat had been coming under fire around town.

"It kind of makes me angry to hear that," says Heeschen. "He didn't have a partner who could keep up with him. Kelly was at a different level."

Psychologist Peter Sheras says there is a human tendancy to blame victims of tragic events. "It's that desire to control your own future," he says. "Life is unpredictable. That's one of the hardest things for all of us. It makes us anxious and nervous."

"You want Kelly to be alive," says Patriot Coach Weisand, "and you start getting mad at him. And you get mad at yourself. But I just can't blame him for being there."

Was Kelly's risk-taking approach responsible for his death?

"Yes and no," says William & Mary coach Gibby. "I don't think he took risks in his training. I guarantee he hydrated properly."

Coach Weisend agrees. "I'm not a doctor," he says, "but I feel like something extraordinary went wrong. He's run incredibly hard workouts in incrediby hot weather. I have to think there was some flaw in his personal themostat."

Weisend says he wouldn't have necessarily told Kelly not to run that day. "I probably would have told him to give it a try, and if you feel bad, then turn around and come back," he says.

There was no autopsy, but Kelly's dad says his son wasn't taking any medications and received only a cleaning that day at the dentist.

Gibby wonders whether there was some small change in Kelly's body– perhaps an undetected illness coming on– that made him vulnerable.

"He probably thought, 'I can do this– it's no different from what I've done before. But it was different," says Gibby. "He had an absolutely iron will, and he probably didn't concede when he should have."

Take back the Ridge

Kelly Watt's friends didn't wait for the funeral. Less than 24 hours after he died, they went back to Ridge Road for a group run. For Kelly.

"It was spur of the moment," explains his friend Heeschen. "We needed to go out there together and get the road back, because it would be a little haunting for one of us to be out there alone."

Everyone was supposed to meet before 8am Sunday, July 31. But the minutes clicked by, and it quickly became apparent that the event wasn't just drawing close friends and teammates.

Former competitors from other schools were appearing. Even a few non-athletes– people who'd never run.

"We parked on the same side he parked on," says Heeschen. "People were a little somber at first. We had a moment of silence and then a group picture."

Then coach Weisand checked his watch and realized that they had missed the planned start time by 15 minutes. "We're on Watty time here," he said.

"That really lightened the mood," Heeschen says.

Psychologist Sheras applauds the run and the previous day's meeting at the high school. "I'm impressed with the community response," he says. "These are all very healthy responses from a community that's healing itself."

"There must have been 60 or 70 people out there," says Mark Lorenzoni, proprietor of the Ragged Mountain Running Shop, the place where Kelly always bought his New Balance "991" shoes.

"All his teammates were there," says Lorenzoni. "But there were kids from Western and Monticello– kids he competed against– and kids from college who remembered him from high school. His life spoke volumes to his friends– and his competitors."

Kelly Watt's desk and a box of writings.

"Not many people really enjoy running," says father Paul Watt. "But he really loved it."

Sister Morgan and mother Paige read a copy of Sports Weekly.

Kelly (bottom left) and friends on Old Rag Mountain.

"He was focused, determined, and he knew what he wanted to do."– Paul Watt