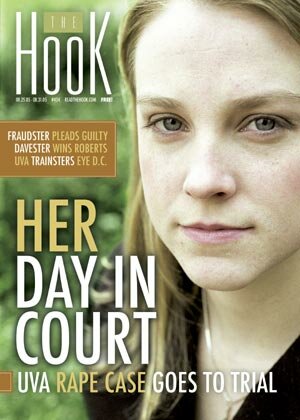

Her day in court: UVA rape case goes to trial

On August 29, nearly four years after UVA student Annie Hylton accused a fellow student of raping her at his fraternity house, her $1.85 million civil suit against him is slated to begin in Charlottesville Circuit Court.

"I'm excited to get my day in court, but you never know what's going to happen," says Hylton, whose case touched off a debate because the alleged attacker, Matthew Hamilton, remained a student– while the alleged victim, under threat of expulsion, wasn't even allowed to discuss the case.

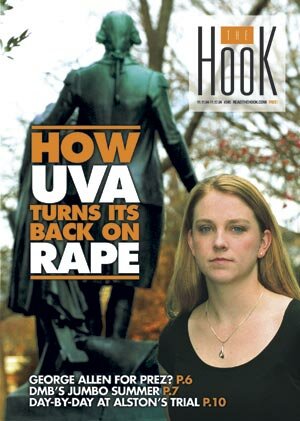

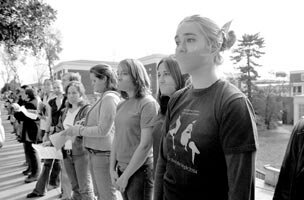

Hylton went public in The Hook's November 11, 2004 cover story, "How UVA turns its back on rape." Tension crested six days later with an on-Grounds protest that drew more than 400 students– many wearing gags to symbolize UVA's policy of forbidding victims to talk about their cases.

***

As the case heads to court, what happened to Hylton has moved far beyond the bucolic Grounds, as various national news organizations are showing interest. The CBS Early Show ran a segment in May on sexual assault at several universities including UVA, and Dateline NBC has interviewed Hylton for an upcoming show.

Now a newlywed living in Washington state for the summer, Hylton probably couldn't have imagined her current legal situation on December 8, 2001, when– as an 18-year-old first-year student and varsity volleyball player– she agreed to go on a dinner date and to a fraternity function with Hamilton, then in his third year.

Her suit alleges that the two dined with another couple at a downtown restaurant, where Hamilton "repeatedly offered" to obtain alcoholic drinks for the underage (but admittedly fake ID-equipped) Hylton. She claims that despite her turning down his offers, he continued to bring the drinks, and she eventually drank "a small amount."

By the time the foursome arrived at a party at the Delta Tau Delta fraternity where Hamilton was a member, Hylton had agreed to play drinking games and quickly found herself "very ill" and vomiting. While "she was aware of some things that happened... she was not able to function and felt mentally and physically impaired," according to her suit.

As she drifted in and out of consciousness, Hylton says, she became aware that she was wearing a t-shirt and that she was in Hamilton's bed. "Mr. Hamilton was not in the bed, but Ms. Hylton was aware that he and one or more other people were in the room," court papers allege.

Then she lost consciousness. When she awoke, "Mr. Hamilton was on top of her engaging in sexual intercourse," according to her suit.

Despite her attempt to get him to stop, the suit continues, "Mr. Hamilton held Ms. Hylton down, continued to touch and fondle her, and attempted to resume having sexual intercourse."

The next morning, Hylton went to UVA hospital, where nurses administered a PERK (physical evidence recovery kit) test, but too much time had elapsed for an accurate blood alcohol content or to test for the presence of so-called "date rape drugs," which Hylton believes Hamilton secretly slipped her.

With a lack of physical evidence– other than proof of intercourse that may or may not have been consensual– Charlottesville Commonwealth's attorney Dave Chapman declined to press charges.

As Chapman explained to The Hook, "he said-she said" charges simply aren't sufficient to win a court battle. "We need to have evidence beyond a reasonable doubt," Chapman says.

Frustrated, Hylton pursued a sexual assault charge through UVA, and while she says the school's sexual assault board found Hamilton guilty of violating the school's code of conduct, the repercussions were minimal. Although he was barred from contacting Hylton and was told to attend counseling, Hamilton remained a student and went on to graduate. She calls the experience "devastating."

Hylton says she was told that all aspects of the hearing– including her alleged attacker's name, the investigation, and the outcome of the hearing– had to remain confidential. She was warned that if she revealed those details, she might face a Judiciary Committee penalty, which could have included suspension or even expulsion.

She kept her word until March 2004. That's when Susan Russell launched uvavictimsofrape.com. Hylton and more than 100 other women came forward and told Russell stories of sexual assault on or around UVA Grounds. Many described their frustration with the school's handling of their cases.

Russell, whose daughter, Kathryn, alleges she was raped at UVA in February 2004, is incensed that in the three years leading up to the launch of the website, 38 students who violated UVA's renowned Honor Code were permanently expelled for lying, cheating, or stealing. And yet, during that same time, Russell found no evidence that any of 60 reported rapes was punished with so much as a suspension.

Hylton, however, did something most rape victims don't do– she went public with her name and the details of her story. And she filed a complaint against UVA with the U.S. Department of Education, claiming that UVA's sexual assault policies were not only unfair– they were illegal. In fact, UVA's confidentiality requirement, preventing rape victims from speaking about their cases, was in violation of federal law.

"If the school at the time had done its job correctly and had followed the federal guidelines set up to protect students from campus crime," Russell says, Hylton "might have been able to enjoy her time as a young coed without the suit looming over her head."

Some, however, lauded UVA's efforts to combat sexual assault.

"UVA funds a women's center with trained advocates who are empowered to help victims," wrote Brett Sokolow, a Pennsylvania-based attorney and an advisor for student conduct issues at five universities. In a November 2004 letter to The Hook, Sokolow cited UVA's separate board for sexual cases and its use of a no-contact order to keep victims and the accused apart.

"All of these things," wrote Sokolow, "demonstrate effort on the part of the university to address these situations."

Following The Hook's article and the silent protest last November, UVA President John Casteen released a statement vowing that the school "will not tolerate acts of violence against students." Casteen also seemed willing to strengthen the penalties for sexual assault.

"I am prepared," Casteen wrote, "to consider the merits of mandatory expulsion as a single sanction."

In March 2005, just four months later, UVA released a revised sexual assault policy that allows both accuser and accused to discuss the case after the hearing process is complete.

And while the single sanction of mandatory expulsion did not survive to the final guidelines, the new rules require the board to consider both suspension and expulsion of students found guilty of sexual assault, the more serious of two possible charges. (The other is sexual misconduct.)

In a memorandum opinion (a confidential document released to both the accuser and accused after the hearing), the board must also explain how it arrived at its chosen sanction.

In addition to its new sexual assault policy, the University is taking steps to make life safer for students. Starting this year, University buses will run until 3am on Friday and Saturday nights so that students will have a safe way home, according to UVA spokeswoman Carol Wood. In addition, UVA, in conjunction with Charlottesville police, will have additional officers patrolling the Grounds and the surrounding neighborhoods until 3am Thursday through Saturday nights.

At this year's convocation on Sunday, August 21, UVA President John Casteen had "sharper" words for male and female students than in past years, says Wood.

Addressing the women first, Casteen said, "You have the right to the integrity of your own person. If you say no, no means no. You have the right to reject someone's advances. You have the right to be safe, to be comfortable, and to be secure."

To the men, Casteen spoke sternly. "I want you to look around you tonight at the women sitting beside you," he said. "These women are your sisters for the next four years, and I want you to understand who they are. You have an obligation to protect them, and I want to be sure that you understand that when you hear no, it means no and that there is no further discussion."

To all students, Casteen stressed the link between alcohol and sexual assault and pointed to "personal responsibility."

In addition to Casteen's stepped-up discourse, the University has increased the information first-year students receive about avoiding, reporting, and stopping sexual assault.

While Hylton is pleased the school is emphasizing education and prevention efforts, in her case, it's too late. She's not alone. After The Hook published her story, she says, she was flooded with supportive messages from women who said they'd been sexually assaulted while at UVA. But one email stood out.

"All the details of your experience seemed eerily familiar to me," wrote a woman who graduated in 2003. Her letter reveals that she, too, had an unhappy encounter with Matthew Hamilton.

The woman said she ran into Hamilton at the Biltmore Grill, where he worked as a bartender. She wrote that she knew him from an English discussion class, and that he started a conversation and then "went behind the bar to make her a drink."

He made her "maybe" two or three drinks, she alleged. "I don't remember much after that, only that I felt way more drunk than I should have been after only two or three."

Though she doesn't detail her alleged assault in the letter, she claimed that, like Hylton, she ended up disoriented and immobile in a room at Delta Tau Delta.

Unlike criminal cases, which routinely discard evidence about other cases as possibly prejudicial to the defendant, civil cases can cast a broader net. For months, Hylton and her attorneys corresponded with the woman, pleading with her to offer her testimony– something they believed strengthened Hylton's case against Hamilton, despite the fact that the other woman had not gone to the hospital for an exam or filed a complaint.

In March, the reluctant witness agreed and gave a deposition that, along with her identity, remains sealed.

As does much of her story. On August 5, Charlottesville Circuit Judge Edward Hogshire ruled that testimony from the woman referred to as Jane Roe would be "unfairly prejudicial to the defendant, and that its prejudicial effect would outweigh its value as relevant evidence."

"We were very surprised," says Hylton's lawyer, Steve Rosenfield, who filed a motion to reconsider five days later. That motion was also denied.

In his motion to exclude Roe's testimony, Hamilton's attorney, Doug Winegardner of Richmond, details 18 ways in which Jane Roe's allegations are "substantially different" from Hylton's.

For instance: "Prior to the alleged sex, Roe did not have a dinner date with the defendant, nor did she dance with him, as Hylton did."

Here's another: Roe alleged that the drinks she received were "green-colored and fruity," while Hylton alleges that Hamilton provided "malt liquor followed by an orange-flavored drink and a vanilla flavored drink."

And while Hylton alleges feeling "completely paralyzed" and "physically incapable of moving," Roe simply alleged that her limbs "felt as if they were too heavy to move."

Roe alleged that after the rape Hamilton sodomized her. In addition, Roe admits that she did not "verbalize anything about stopping." Why not? The document doesn't say, but in her initial letter to Hylton, she wrote she was "not really coherent enough to do much of anything besides just lie there."

Winegardner's motion claims that when asked what details of her experience match Hylton's version, Roe responded, "The line in The Hook that says she was aware of some things that happened, she was not able to function and felt mentally and physically impaired. Also, when she awoke, Mr. Hamilton was on top of her engaging in sexual intercourse." In addition, Roe claimed, her nausea was similar to Hylton's.

The similarities between Hylton's and Roe's descriptions are "typical of 'date rape' attacks on college campuses," wrote Winegardner, "and are not so factually similar or idiosyncratic to warrant admission into evidence under the limited exception."

Contacted through Hylton's attorney, Rosenfield, Roe declined to be interviewed.

Through Winegardner, Hamilton also declines comment on the pending case. But Winegardner says both he and Hamilton were "very surprised" when Jane Roe made her allegations. The court's decision to exclude the evidence "was correct," says Winegardner, who repeats that Roe's and Hylton's allegations were "not at all similar."

Hylton must now proceed with the case without Roe's testimony. She does, however, have the testimony of several expert witnesses, including Eugene Corbett, a physician and professor at UVA's School of Medicine, who will testify he believes Hylton was drugged on the night in question.

Winegardner, however, says he's confident the jury "will exonerate Mr. Hamilton after it sees all the facts and all the evidence."

Hylton, meanwhile, hopes the jury will believe her story and award her nearly $2 million, some of which she plans to donate to "different Charlottesville agencies and to UVA."

But even if she wins the case, she may not see a dime.

On May 23, Middlesex Mutual Assurance Company, the company that provides homeowners' insurance to Hamilton's parents, William and Alison, who live in New Hampshire, filed suit against Hylton and Hamilton, arguing the company should not be liable for any judgment against Hamilton in this case. Because he was a student at the time of the incident, he was covered by his parents' policy, but Middlesex excludes coverage for criminal activity including "sexual molestation."

Winegardner says the insurance suit is not surprising. "That kind of action is very typical to determine rights and obligations," he says.

If Hamilton successfully defends himself against Hylton's suit, the insurance issue is moot, says Winegardner. If Hylton prevails, Middlesex Mutual's case will be heard in U.S. District Court, though no date has been set.

Hylton is still working on her joint bachelor's/master's degree in biology/teaching by working as a student teacher for the upcoming academic year in Fairfax County. Her new husband, Mark McLaughlin, a Navy pilot, will deploy to the Persian Gulf on the first day of her trial.

Hylton recently accepted a position on UVA's newly formed sexual assault advisory committee. "I really do think they're trying to change," she says of the school.

Whatever the outcome of the civil case, Hylton says going through the legal process is "definitely important." And if the jury finds for Hamilton, she says, she'll move on.

"If it doesn't go my way, it's more the system's fault," she says. "I want to show other women they can go through it."

Annie Hylton first went public in The Hook 's November 11, 2004 cover story. "I feel like he messed with the wrong person." –Annie Hylton

Now living in Brooklyn with a job in finance, Matthew Hamilton, shown here in a first-year photograph, has declined comment on the suit.

The Delta Tau Delta house, site of the alleged attacks on Hylton and "Jane Roe," a second woman, who was excluded from the trial.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Susan Russell, parent of an alleged victim, launched uvavictimsofrape.com last year.

Susan Russell, parent of an alleged victim, launched uvavictimsofrape.com last year.

TWO-PART PHOTO LUMP:

More than 400 students turned out to protest last fall in McIntire Amphitheater.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Jill Raney and other students at the November 17, 2004 gathering donned symbolic gags to protest UVA's "code of silence."

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

BIG TEXT:

In the months following the alleged assault, Hylton says, she lived in fear of a run-in with Matthew Hamilton. She had trouble sleeping and eating, and at several points contemplated suicide.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

BIG TEXT:

"These women are your sisters for the next four years. You have an obligation to protect them." –John T. Casteen III, August 21, 2005

UVA NEWS SERVICES/DAN ADDISON