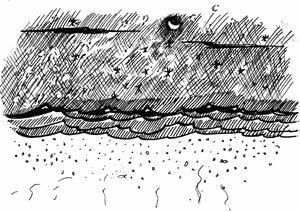

Up and down: Plankton check out the surface

DRAWING BY DEBORAH DERR McCLINTOCK

Q. It was World War II, and the sonar-operating submarine searchers detected a "false bottom" of the sea that rose toward the surface every evening, then sank back down again the next morning. What was the enemy up to? –E. Zumwalt

A. Not the enemy but rather myriad plankton, tiny crustaceans and other creatures that rose to feed near the surface by night, then returned to the depths as daylight came on, says Richard Dawkins in The Ancestor's Tale.

Why do this? The best guess is that during daylight hours these sea creatures are visible and vulnerable to hunting predators, such as fish and squids, so the dark depths offer safety. But the sunny surface is where the food is, that unbroken green prairie of microscopic single-celled algae in the role of waving grass.

"Here's where the grazers, and those that feed on the grazers, and those that feed on them, must be," Dawkins says. So a diurnal migration is exactly what the grazers and their small predators must undertake. As one observer put it, "It's a little like a human walking 25 miles daily just to get breakfast."

Q. Right now, can you say what time it is without checking? If you needed to awaken at a certain predetermined time without an alarm clock, could you do it? –S. Thomas

A. You could if you have an uncanny "time sense" like British physician Winslow Hall, who out of 100 sleep trials (1927) was able to awaken himself within 15 minutes of the target time more than half the time, and exactly right (within a minute) 18 times, says Jay Ingram in The Velocity of Honey. Many claim to be able to do this, and sleep labs have backed them up. Probably it's done by somehow keeping track of dream (REM) periods through the night.

But Hall took this a step further, tracking the time asleep or awake. When he and three friends tested each other by randomly asking, "What time is it now?," 45 percent of their guesses were correct within three minutes, 10 percent were just about dead on.

One of Hall's devices was to picture the face of his watch while still in his pocket, and to simply read off the time from the imagined clock face!

For one of his successful awakenings (July 10, 1917, 4:30am), he saw in a dream a hand-lettered sign that read "Truth." It woke him up at the target time. Most of us are absolutely hopeless at this, missing by hours, though some can do it at least some of the time. People with a good time sense generally know it, with their self-awakenings about as accurate as their daytime estimates of time passage. "That does suggest there is some kind of internal timekeeper that is consistent 24/7," says the researcher.

Q. You're asleep and now you're dreaming. How might you signal to someone at bedside that the show is on? –S. Freud

A. This was part of a sleep lab demo by Stanford researcher Stephen LaBerge to show that lucid dreams– where the dreamer realizes it's only a dream and may "steer" the action– occur in full sleep like other dreams and not during a brief awakening. Late that night, LaBerge had his first lucid dream. Suddenly he remembered where he was, and saw himself reading a book in bed in a room just like the lab. As prearranged with the staff, he now pictured holding up a finger, then moved it up and down while following it with his eyes. Up and down, up and down went his dream finger and dream eyes.

Breakthrough! The bedside polygraph recording showed two large scanning eye movements near the end of LaBerge's 13-minute dream period– premeditated movements clearly distinct from the ordinary "rapid eye movements" of dreams. Communication had crossed in historic fashion the boundary of silence between a sleeper and the world around him.

Q. How many moons are bright enough to be seen in our sky with the naked eye? –T. Brahe

A. Wonderful trivia question! The answer is five: our own moon plus Jupiter's restless quartet, says astronomer Bob Berman in Secrets of the Night Sky. Four centuries ago, using a rudimentary telescope, Galileo spotted them first, sometimes all four on one side, or three and one, etc., or maybe one hidden. They're named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, and in the days when Britain ruled the seas, mariners with spyglasses would check out the positions of these Galilean satellites, consult secret tables by England's Royal Astronomer, and know the time, and thus the ship's longitude.

"For over a century people found their way around our planet by watching the moons of another," says Berman. Takes someone sharp-eyed to see these moons unaided, and a child's eyes will often do. Many a parent has passed along the scope to the 7-year-old, directing her to look at the "little dots to the right of Jupiter," but she's already spotted them, "No, they're on the left." (Telescopes flip the image.)

Send Strangequestions to brothers Bill and Rich at .