Crumby news: Museum may be toast

They came to Charlottesville full of hope, and hauling toasters about 700 of them. But after seven years of working to open a museum for their collection in their Carlton Avenue home, Eric Norcross says he and his wife, Kelly Godfrey, have had their fill and decided to pop away.

"The project has run on for so long that we've lost steam on it," says Norcross.

Their massive toaster collection began to take shape in 1990 in Seattle, where Norcross owned a tiny art gallery and coffee shop. Trying to expand his food offerings, he decided to place a 1950s toaster on each table and allow patrons to make their own toast. He and Godfrey began scouring antique stores for toasters, and soon they were hooked.

"A lot of energy had been put into these objects," he says. "It was a fun archaeological hunt at the time." Over the years, Norcross and Godfrey collected nearly every toaster ever made– from a 1909 General Electric– "the first successful toaster marketed for the home"– to the 1930s art deco Hot Toast Gazelle Toaster to the Michael Graves-designed modern model sold at Target.

When the couple decided to move cross-country to Charlottesville in 1998, they hoped the historic and arts-friendly community would embrace the concept of a toaster museum, and that funding would flow.

Such was not the case, says Norcross now, a month after deciding to throw in the towel. "Basically, it was a lack of resources," he says.

The Toaster Museum's website, toaster.org, reveals that of $30,000 Norcross and Godfrey had hoped to raise toward renovating their building, they have so far received only $1,500.

"We went to the city to see if there were development loans, but we didn't get much help with them," Norcross explains. "It would have been cheaper to use credit cards."

Particularly frustrating, he says, was watching DMB manager and mega-developer Coran Capshaw receive help from the city to build the new Pavilion at the east end of the Downtown Mall.

For that project, the city gave Capshaw a $2.4 million loan to be repaid over 20 years at 3.7 percent interest. In addition, the city offered a $1 million "contribution"– a zero-interest loan that Capshaw will repay with a $.50 surcharge on each Pavilion ticket. (The City gets to keep the Pavilion when Capshaw's lease ends in 30 years.)

"They could have helped out a lot of little guys," says Norcross, "rather than one big guy."

But Aubrey Watts, director of development for the city, says the City is not in the business of giving small business loans. Those, he explains, are handled by the state's Small Business Development Center, which has a regional office in Charlottesville.

Though they couldn't offer Norcross and Godfrey a loan, says Watts, he and his staff "spent an awful lot of time with them, trying to help them."

The help, says Norcross, simply wasn't enough.

While their dream of seeing the Toaster Museum open in Charlottesville may be going up in smoke, all is not lost for Norcross and Godfrey– in fact, far from it, thanks to Charlottesville's booming real estate market.

"The property itself was more valuable as a development site," says Norcross. "It made more sense to sell it and move on."

Indeed. In 1998, Norcross and Godfrey paid $85,000 for their approximately 2,100 square-foot, 1920s home on 1/3 acre in Belmont. Today, the property is on the market as a "development opportunity." Asking price: $795,000 more than a 900 percent return, should they get it.

And there's already been interest in the property. "We have a letter of intent," explains listing agent Roger Voisinet, who declines to reveal the details of that letter or the name of the potential buyer.

And there may be good news for the toaster museum as well.

Norcross says that potential buyer has expressed interest in incorporating the toaster museum into the new project's design. Not only would it draw visitors to the mixed-use site, he says, but the museum's nonprofit status would also provide its landlord a tax write-off.

If that arrangement doesn't work out, Norcross says, he still hopes the toasters will remain together and that they will eventually be displayed, perhaps at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, which features a variety of artifacts from American homes over the last century.

Whatever the case, it's time for someone else to carry the toaster torch, says Norcross, adding that he and Godfrey have new callings.

"We're hoping to move to Stratford, Ontario," he says. "I'm going to focus on my art work, and we'd like to open a bed and breakfast."

They may want to hang onto a few of those toasters after all.

Eric Norcross and Kelly Godfrey hope someone else will carry on the toaster torch.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

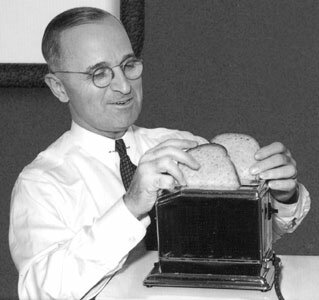

Along with hundreds of toasters, the Toaster Museum would have featured historic toaster advertisements and photographs such as this one of President Harry Truman happily making toast.

PHOTO COURTESY THE TOASTER MUSEUM