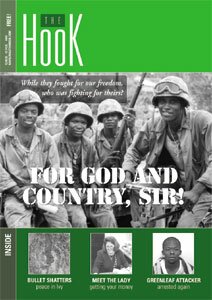

For God and country, sir! While they fought for our freedom, who was fighting for theirs?

PHOTOS BY JEN FARIELLO

Even now, 59 years after he was mustered out of the U.S. Army, Howard "Hank" Allen still bristles when he remembers his experience during World War II. It wasn't the danger– even though he was in the fiercest war zones in Normandy and other parts of France, where, as he says, "We were getting our butts kicked by the Germans."

It was the insult.

Even with two years of college behind him when he was drafted, he was considered too dumb to serve in combat. Why? Because he's black.

This African American, considered not intelligent enough to fight for his country, eventually earned a doctorate in education, taught at the University of Virginia, and perhaps most proudly– chaired an organization that helped hasten desegregation.

"Even before I was drafted into the army in 1943, the secretaries of Defense and Navy issued declarations stating that we were too stupid to be in combat," Allen says. "I had two years of college at the time. White boys who didn't get past the eighth grade could fight, but I couldn't."

Instead, Allen was relegated to the quartermaster corps, where it was his job to transport fuel to trucks.

Allen related his story for the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress– which in Central Virginia is organized by the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society– and for the StoryCorps project, which is making audio tapes for the Library's archives.

Horace Boykin also related his story for the Society. His experience was not the same as Allen's. Boykin, now 80, recalls that while he was in Okinawa and Saipan, "When it got hot, we were ordered to fight in the front lines for short periods of time."

Horace and his wife, Maude, have a frayed yellow newspaper clipping reporting white and black soldiers in Saipan fighting side-by-side, an indication of how unusual the situation was. Boykin's all-black platoon's typical assignment was to load and unload ammunition from trucks behind the front lines.

"The white soldiers would often tell us we were lucky we weren't in the front," he says.

Allen, Boykin, and Mason Allen, who was also interviewed for the Society, served in segregated armed forces. Their reactions to that period of their lives are similar in some ways, different in many others.

Hank Allen

"First we were in Mississippi, and that was a shock for those of us from the North," recalls Howard "Hank" Allen, who served from 1943 to 1946. "From there we went to Illinois, where we thought we would be accepted, but it was worse.

"Then we shipped out on the Queen Elizabeth from Hoboken to Scotland. It was better in the British Isles; the English people treated us very well. We had more problems with the white soldiers."

His group was posted to Normandy. History has recorded the heavy fighting and casualties in those post D-Day battles. But blacks were not allowed to fight.

"We were getting our butts kicked," Allen says. "One evening, the captain came to the back lines and said anyone who wanted to could volunteer to be in combat.

"I went to the captain and told him, 'I don't feel very good about this. I wanted to be in combat, but I wasn't considered smart enough. Now that we're getting kicked, you want us to lose our lives. If you direct me, I'll go, but I will not volunteer.'

"And I did not volunteer. I have no guilt about that whatsoever. From that day to this, I resent that."

Allen and the other black American servicemen had left a segregated country. And after their serving their country, they returned to the same situation.

"We had sacrificed so much that that hurt deeply," Allen says. "That's why we got behind the civil rights movement." He participated in demonstrations and met Dr. Martin Luther King. But Allen's important role in ending segregation came later.

Allen was born 85 years ago in Dolphin, a bend in the road in Brunswick County, where his father was a farmer. His family moved to New Jersey in 1927, and he attended an integrated high school.

"I sat with white kids, rich kids, poor kids," he says. After high school he attended Hampton Institute in Norfolk (now Hampton University) for two years. Then he married Ruth, a woman he had met at Hampton. They had two daughters, one of whom died in childhood. He and Ruth were married for 60 years, until her death in 2001.

After his discharge from the army in 1943, Allen returned to his studies at Hampton and graduated in 1950 with a degree in physical education. After earning his master's degree at NYU, he moved to Danville and worked in the school system for the next 17 years.

In 1969, a friend who was a professor at the University of Virginia brought Allen to Charlottesville to work at the Consultative Resource Center on School Desegregation in the Curry School. The federal Department of Education had created 27 centers throughout the United States to help public schools desegregate. Allen was a group leader.

"In the South, for the most part, blacks and whites did not communicate," Allen says. "Now, with the desegregation of schools, we knew we were going to have problems."

But the biggest problems he encountered were not in the school. Grown-ups posed a huge stumbling block for integration. Getting the adults, black and white, to talk to and respect each other was a full-time undertaking.

"With the students, [one question was] who is going to be the student council president?," Allen says. "It can't be chosen by election, because the white kid would always win. So we decided on co-presidents.

"Life has improved since then, although we still have segregation," he notes. "By having advanced placement courses, we separate students. As an educator, I know that when you separate the best students you lose something the chance for students to teach other students.

"The first thing I would want for black children is to be well-educated so they can think and make decisions," says Allen, who received his doctorate from UVA in 1973. "Education is the only thing that's going to help us. Once you are educated, they can't take it away."

Allen was director of the center on desegregation from 1973 to 1980, when it closed, as well as a professor at the Curry School. He retired in 1986.

"Since then I've been doing what I want to do for a change," he says. "I'm very busy in my church and with the Masons." Allen and his wife have daughter, three grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

And his memories of the battles he was not allowed to fight.

Horace Boykin

Horace Boykin has a different reaction when he thinks about the war. He laughs. He and his wife, Maude, are laughing so hard they can hardly finish relating an incident about his homecoming.

After the war, troops were returning to the States.

"We were on a train coming through Alabama and decided to get off to celebrate," he says. "Well, the MPs came chasing us [the black servicemen], ordering us to get back on the train, hollering at us, asking what we thought we were doing! We were asking, 'Is this what we fought for? Is this what we're coming back to?'"

They also laugh when they remember when Boykin overstayed his leave and was thrown into the brig when he got back. "I was put in the brig several times," he says. "They were trying to discipline me, and I was being hard-headed."

Boykin enlisted in the Marine Corps before he finished high school, following his brother who had already signed up. "I wanted to do something for my country," he says. After training, he was sent to the Pacific theater. He was in Okinawa, Saipan, Tinian, and Guam.

While he was guarding an ammunition dump during a Japanese air raid, he was hit in the arm, either by shrapnel or a bullet. As he was being treated in a tent hospital, he looked up to see the sky through the holes caused by enemy fire.

"I looked at that and thought I'd be safer in my foxhole, so I got out of there as soon as I could," he says. Boykin is justifiably proud of his Purple Heart.

Back home after the war, he finished high school and then worked as a waiter before becoming a postman, a job he held for 25 years.

"I loved being a postman," he says more than once, "and the money was good." After his post office stint, he worked as a waiter at the Omni hotel until his retirement.

Horace and Maude married in 1946 and have three children. When the children were old enough for Maude to begin her career, she attended nursing school at UVA, and for 26 years she worked as a nurse specializing in oncology.

"When I think back on the war years, I just laugh," Boykin says. "They were hard on us, but it wasn't because of race. The officers were hard on all of us."

And when there was discrimination? "Well, that's how it was back then," he says philosophically, "and there's nothing to do but laugh."

Mason Allen

Mason Allen (no relation to Hank Allen) agrees with the Boykins– but he doesn't laugh.

"I was born in Newport News in 1921. I went to segregated schools, lived in a segregated city in a segregated state, and served in a segregated Army," he says. "I was used to it. I can imagine someone born up north would not be."

But there was a period that was so bad that even Allen, a man raised in the South, could not get used to and it was at the hands of civilians.

Drafted in 1943, Allen served until the end of the war in an Army amphibious transportation company. He trained first in Louisiana and then at a camp in Florida. While there, he experienced the worst direct discrimination he had ever known.

"In Charlottesville, no one talked to you the way they did in Florida," he says. "They called you names, and on public transportation you were harassed by the police." Eventually, Allen stopped taking public transportation and used only Army conveyances.

Then he was shipped to Hawaii for more training. "Hawaii then wasn't as it is now," he recalls. "It wasn't so built up, and it was beautiful." Allen was stationed on Oahu, and because the island had been taken over by the military, he didn't experience any discrimination there.

"While we were training for whatever we never got to do," he says, "the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, and they gave up. It was the end of the war.

"We had a great big beer party."

While during the war the army had only white officers, six months later, when American troops were disposing of ammunition by dropping it into the ocean, he remembers seeing black officers on board the ship.

"When I left for the Army, I didn't know if I'd ever be back," Allen says. "Now that I was back, I knew that during that time, I had grown up."

Allen had worked on a farm before he was drafted, but back home, the veteran with a wife and two children set off to find a job. He found one immediately driving a truck for Charles King Wholesale Grocery.

"The president had remembered my grandfather," he says, "so I got the job. That was a miracle. I replaced a white man, which was unusual at the time."

Allen drove the truck for 16 years and then worked for 24 years for Peoples National Bank, eventually becoming supervisor of the maintenance crew.

"I can't say enough about how life has changed since the war," he says. "I've been to New Orleans, to the Bahamas, and even to Florida. Now I can use facilities the same as everyone else."

***

As Mason Allen says, he had "grown up" during the war. So had the nation. Shortly after V-J day, he saw the beginnings of integration– African Americans became part of the officer corps.

Hank Allen was a part of the new generation that would make the system work. Now, Mason Allen can travel freely in the part of the country where he once was most humiliated.

Even as Horace Boykin can laugh at the discrimination he was forced to endure, and Hank Allen still bristles remembering his experiences, they can all take pride in the roles they played not just to preserve freedom in the world, but to make life better at home– for themselves and for the generations that followed.

Bea Mook is a Charlottesville-based freelance writer.

Hank Allen

Mauric Boykin

Mason Allen