Subsidy? Critics decry Breeden tax break

Only four short years ago, Charlottesville was agog at what was then the most expensive real estate transaction ever: former Tyco CFO Mark Swartz's $17 million purchase of the Enniscorthy estate.

Real estate bubble bursting or not, three sales this year dwarfed the Enniscorthy deal, and developer Hunter Craig now holds title to the biggest buy in Albemarle history– $46.2 million for 1,365-acre Forest Lodge on Old Lynchburg Road.

(First runner-up is Fred Scott's Bundoran for a reported $33 million, followed by Castle Hill for $24 million.)

The sale of the Forest Lodge tract surrounding David and Elizabeth Breeden's artist enclave, Biscuit Run, has particularly irked critics of a tax break designed to preserve rural open space.

With Forest Lodge's pending development into as many as 4,790 residential units– blandly dubbed "Fox Ridge"– those critics are saying Use Value Taxation, a.k.a. land use, clearly doesn't work to preserve rural acres by offering a lower tax rate for agricultural uses.

The Forest Lodge sale is "another example of how ineffective the land use tax break is at preserving land," says Charlottesville gadfly Kevin Cox.

In the case of Forest Lodge, its owners have gotten a break since 1975 on one of the 10 parcels, even though, by their own comments, they've always known that the land two miles south of town ultimately would be developed. That 131-acre parcel has a market value of $2.46 million, according to Albemarle County; under land use it was taxed at a value of $42,000.

Another parcel in the deal has a fair market value of $10,524,100. Under land use, Albemarle assesses its tax value as $297,000.

"That's money down the tubes," says longtime land-use critic Tom Loach. "What good did it do the county?" He calls land use a "subsidy" for the rich that leaves development rights intact. Instead, he believes Albemarle should invest in the Acquisition of Conservation Easements program to keep rural land rural permanently.

Albemarle Supervisor Sally Thomas defends the Breeden family's tax break on land destined to be developed. "Every year that we keep it out of development, we're helping other taxpayers. Cows don't go to school," she says, referring to the high cost of services for residential growth.

And unlike murder, in land ownership, premeditation doesn't factor into the tax rate. "What you're taxing is the land," says Thomas, "not their profession or their intentions or their character. The Breedens kept the land open for years. It could have been developed 10 or 15 years ago with 5- and 10-acre lots."

Loach contends that land use cost the county $13 million in deferred taxes it didn't collect in 2004, and the tax rate could drop 10 cents– from $.74 to $.64 per $100– if land use were abolished.

"It's a very fair tax," counters Thomas. "If you have 50 acres and are farming, you shouldn't be paying taxes as if it were a subdivision you were planting houses on. Just like if you have a house, you're not taxed as if you're Wal-Mart. [Property] is taxed for what it's used for."

Loach has another plan: take the $13 million deferred under land use last year and invest in the ACE program to permanently keep acreage open. "If the goal is to preserve rural land, it's better to invest than subsidize," he argues.

Unfortunately, property owners aren't lining up to enroll in the program. "The ACE program is not finding it has more applicants than money," says Thomas. "It's not like there's this pent-up desire to sell development rights."

One alleged deterrent for land use abuse is the rollback. Craig– when he gets rezoning approval for Fox Ridge– will have to pay the full tax rate for the past five years. For the entire 1,365 acres, that works out to between $500,000 and $600,000 plus 10 percent interest for each year.

However, the rollback applies only to the portion that's taken out of land use. Currently, Craig is trying to rezone 870 acres of the 1,300-plus parcel to build between 2,500 and 4,970 residential units, plus 300,000 square feet of commercial space. The rest of the land can remain in land use.

Critics and supporters would like to see the rollback period lengthened to 10 years. "Every year, we ask the General Assembly for a greater rollback," says Thomas. And Cox thinks property owners who enroll in land use should be required to stay in the program 10 years.

"A lot of farmers look at selling their land, and Hunter Craig is their retirement fund," remarks Cox.

"Use value is not a discouraging factor to development," says the Piedmont Environmental Council's Jeff Werner. The PEC– which never met a conservation easement it didn't like– isn't quite sure whether land use is an appropriate vehicle to stanch development. "We don't want it to go away, but we don't want to see it abused," says Werner. "We need a blue ribbon panel to take a look at this," he suggests.

The huge Fox Ridge development apparently has touched a nerve. "The range of emotions on the Breeden property is astonishing," Werner says. "It's in the growth area. How do you say no to that?"

I.J. Breeden, the patriarch who believed that Charlottesville would eventually grow to the south, has 20-some relatives splitting the proceeds from the county's largest land sale to date. His son, David, and David's wife, Elizabeth, get the house they're living in and 36 acres as their share of the estate. "Our 36 acres stay in land use," notes Elizabeth Breeden.

And she is not apologetic about the tax break the family got for planting trees and having cows. She asks instead if they should have been penalized because I.J. Breeden had the foresight 35 years ago to predict growth would eventually flow in his direction.

She believes one of the reasons the property garnered such a huge price was its size. And clustering houses according to the county's neighborhood model will give the gigantic development lots of green space– rather than the tree-flattening sprawl she sees in Northern Virginia.

"I see Mill Creek South that Hunter Craig built that follows the contours of the land," she says. "The more you don't intrude on the land, the better."

Forest Lodge, probably the last large, close-in property, continues to enjoy the land-use tax break– up until construction begins on 2,500-plus residences and 350,000 square feet of commercial space ultimately destined for the former Breeden family tract.

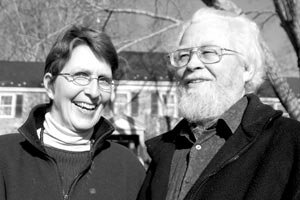

Elizabeth and David Breeden are in the middle of the largest land sale yet in Albemarle County– an eye-popping $46.2 million.PHOTO BY LAUREN BROOKS