Parking pleasure: New Street garage wows Staunton

This is the second in a series of occasional stories about Staunton.

In the early-1970s, the old Strand Theater in Staunton was torn down to make room for a parking lot. The Strand, a Mission-style building on South New Street, gained fame in the Statler Brothers' song Strand on their 1973 album, Carry Me Back, mourning the loss of the old theater where they used to watch cowboy movies:

We came to watch our heroes ride the silver screen

In hot pursuit of Blackie's outlaw band

I wish that I could walk up to that ticket booth again

And buy just one more ticket to the Strand.

It's also a stoic anthem to urban renewal:

But our town is changin' and it seems we need

A parking lot to help our town expand.

Today I learned a lesson, like you, I must be brave

Today I learned they're tearin' down the Strand.

Unfortunately, the parking lot that replaced the Strand may not have really helped Staunton expand.

"In the late 70s, that was the deadest part of town," remembers architect Kathy Fraizer. "Now it's one of the busiest corners in Staunton."

That's thanks in large part to the work of Fraizer and her firm in revitalizing downtown Staunton– in particular, their New Street Parking Garage project that went up over the Strand-eating parking lot in 2000.

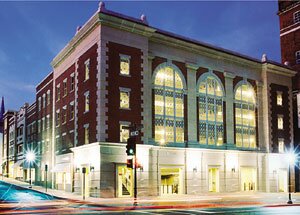

Unlike the parking lot that destroyed the city landmark, the New Street Parking Garage has become one. Of course, when we think of interesting, landmark architecture, we don't normally think of parking garages. Next to parking lots, most parking garages are as visually compelling as– well, parking lots. In fact, parking garages– think of the ones on Water Street, Market Street, and UVA's new structure on Ivy Road– are either so utilitarian or downright ugly that we tend not to even think about them as "architecture."

In contrast, the New Street Garage announces itself in the classic form of an old railway station like Grand Central in New York or Union Station in D.C. In fact, that's what Frazier and her team had in mind when they began brainstorming for a design.

"In the past," says Frazier on her company's website, "architects designed beautiful buildings for visitors to arrive in. Somehow that didn't get translated to parking garages, and people grew accustomed to parking in these ugly utilitarian buildings. The question we asked ourselves is 'Why can't we make a parking garage beautiful and celebrate the arrival sequence like we used to with train stations?'"

The result is a utilitarian building without a utilitarian design. In addition to providing space for 270 cars, direct access to the newly renovated Stonewall Jackson Hotel and Blackfriars Playhouse, and seven store fronts that meld seamlessly into the turn-of-the-century architecture on New Street, the new garage's elegant arched windows and elaborate brickwork make it something to stare at, especially at night when the lights are on. And that's saying a lot for a parking garage!

On street level it's also remarkably unobtrusive, almost invisible. Standing on the street corner only a few feet away, it's hard to tell it's a parking garage. The entrances are so compact that the structure of the building is apparent only from inside, kind of like entering the Bat Cave.

Of course, none of this has gone unnoticed. In 2002, the New Street Garage Project won Traditional Building Magazine's Palladio Award for new design and construction.

"Perhaps one of the more significant contributions of this project," reads the 2002 citation, "is that it has moved parking-garage design into a new and more elegant category, along with other civic structures, instead of being considered as only plain, ordinary buildings."

In addition to helping revitalize downtown, the project assisted the renovation of the 1924 Stonewall Jackson Hotel, which– after decades of being only slightly more than a flophouse– reopened September 21, the beneficiary of a two-year, $21 million upgrade into a luxury hotel/conference center.

"They never would have renovated the hotel if we hadn't done the parking deck," says project manager Carter Green.

"Hats off to the city of Staunton," says Frazier. "It was their commitment to preserving the architectural character of downtown that made it possible. We've held on to our architecture much better than other downtowns."

Of course, that commitment hasn't been cheap. The New Street Garage cost taxpayers $4.3 million, and City fathers kicked in nearly $9 million to create the conference center.

That's quite a commitment to downtown. Some would even say it's a risky gamble. As Charlottesville taxpayers learned when they funded the Omni Hotel in 1985, if the hotel doesn't turn a profit, it's Staunton citizens who'll have to foot the bill.

In a 2004 Hook article ["City on a hill: Is Staunton the next Charlottesville?"], University of Texas prof Heywood Sanders noted, "The question that has to be asked is what does Staunton envision itself becoming?"

"Right now we're on the upswing," says Frazier, who remembers when Staunton was so dead she could stand at the intersection of East Beverley and New streets at night and not see a car for hours.

"One of the rewards of getting older is being able to see how much things have changed," she says. "Now there are shops and restaurants and boutiques and a real vibrant scene downtown. And that's very gratifying."

The New Street Garage shines as one of Staunton's most successful civic architecture projects.

PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR