Shenandoah secrets: Pork, propaganda, and the creation of a COOL national park

-

PHOTO NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

PHOTO NATIONAL PARK SERVICE -

Putting a road atop a National Park was a novel concept-- and one that probably won't be repeated.National Park Service

Putting a road atop a National Park was a novel concept-- and one that probably won't be repeated.National Park Service -

Retired UVA researcher Nancy Martin-Perdue began hearing stories about the displaced when living in Rappahannock in the 1970s.photo by Lisa Provence

Retired UVA researcher Nancy Martin-Perdue began hearing stories about the displaced when living in Rappahannock in the 1970s.photo by Lisa Provence -

"Wife and child of squatter, Old Rag, Virginia," reads the original caption. No matter how long they'd dwelled or what they'd built, anyone without land title was considered a squatter.National Park Service

"Wife and child of squatter, Old Rag, Virginia," reads the original caption. No matter how long they'd dwelled or what they'd built, anyone without land title was considered a squatter.National Park Service -

Mrs. George Bailey Nicholson at her home in the Madison County enclave of Corbin Hollow. She was widowed in 1931 when a chestnut tree fell on her husband, a preacher. The government paid $910 for her house and 25 acres.National Park Service

Mrs. George Bailey Nicholson at her home in the Madison County enclave of Corbin Hollow. She was widowed in 1931 when a chestnut tree fell on her husband, a preacher. The government paid $910 for her house and 25 acres.National Park Service -

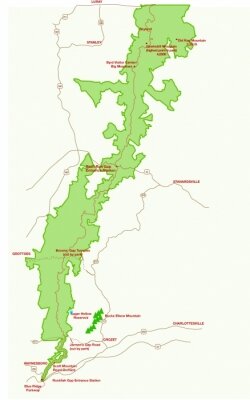

Shenandoah National Park partial map.

Shenandoah National Park partial map. -

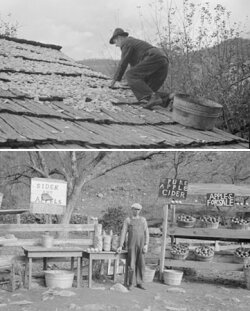

Drying apples, "one of the few sources of income for mountain folk," and a cider and apple stand on Lee Highway near the northern tip of the park.PHOTOS NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Drying apples, "one of the few sources of income for mountain folk," and a cider and apple stand on Lee Highway near the northern tip of the park.PHOTOS NATIONAL PARK SERVICE -

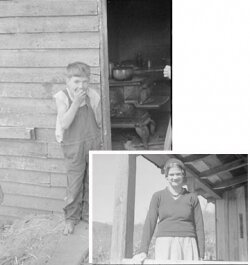

"Half-wit Corbin Hollow boy" and Virgie Corbin, who "has the mentality of a child of seven," according to original federal photo captions.NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

"Half-wit Corbin Hollow boy" and Virgie Corbin, who "has the mentality of a child of seven," according to original federal photo captions.NATIONAL PARK SERVICE -

The most famous "squatter removal" was the eviction of pregnant Lessie Jenkins.

The most famous "squatter removal" was the eviction of pregnant Lessie Jenkins. -

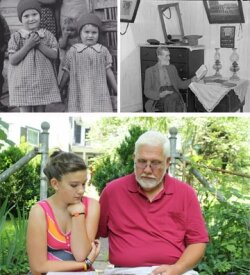

Jimmy Brown (shown with daughter Caleigh-Ruth) is the great-grandson of the postmaster of the now-vanished town of Old Rag, William Austin Brown, above right, who was grandfather to the three girls above.PHOTOS NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, LISA PROVENCE

Jimmy Brown (shown with daughter Caleigh-Ruth) is the great-grandson of the postmaster of the now-vanished town of Old Rag, William Austin Brown, above right, who was grandfather to the three girls above.PHOTOS NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, LISA PROVENCE -

Ruins of a former home in Corbin Hollow.NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Ruins of a former home in Corbin Hollow.NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

A lot can change in three quarters of a century. Walk along the Hughes River in Madison County in a place called Nicholson Hollow, and there's little trace that this was once a thriving village.

Now heavily wooded, the hollow was a lot more open then because trees had been cut since the late 1700s to build houses, barns, and fences, and the land left open for gardens, orchards, and pastures for cattle and horses. Seventy-five years ago, the hollow became part of the East Coast's first national park when it opened after heaps of controversy.

Jim Lillard's grandfather, W.A. Woodward, owned a 154-acre farm in Nicholson Hollow. Lillard pulls out a plat that shows not only the location of the frame farmhouse but also identifies the owners of neighboring farms, as well as the sites of the school, church, mill, and road.

"If you look at that, you could see a community thrived," says Lillard. "It really was a civilization, not a bunch of hillbillies."

But 75 years ago, the residents of Nicholson Hollow were indeed portrayed as hillbillies, even successful, educated farmers like Woodward. Photo captions in the Library of Congress mention a man with a "rude sled" and describe one child as a "half wit."

In the winter, stone chimneys and foundations can be spotted here, but in late June, unless you're sharp-eyed, there's no evidence that people lived here for generations. And that's what the creators of the Shenandoah National Park intended.

Just about the only thing that hasn't changed over the past 75 years– or the past 7,500 years– is the sound of the Hughes River cascading over rocks down the mountain.

Easterners need a park

At the beginning of the 20th century, millions of acres in the American West had been corralled into national parks, and Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work wanted one east of the Mississippi in the Appalachians. Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia vied for the honor, "this choice morsel of political pork," as historian Andrew H. Myers put it in a 1993 article.

Then as now, Washingtonians couldn't help but savor the idea of a park just 60 miles from the nation's capital, and Virginia had boosters who were willing to drum up donations to buy potential parkland and then donate it to the federal government.

Two leaders of that pack were Harry Byrd and George Freeman Pollock. Byrd was then a state senator (and later, as U.S. senator, leader of the state's notorious Massive Resistance– and yes, the park initially was segregated). However, it's Pollock who's most often cited as the key instigator by those who lost their land to the park.

Not coincidentally, Pollock owned a mountaintop resort called Skyland, where, before the advent of the automobile, the well-heeled would head by horse and buggy to the cooler clime atop the Blue Ridge Mountains to spend a month or more on holiday. By the early 20th century, car culture was irrevocably changing America, and yet Pollock's resort was struggling.

"People had cars and wanted to travel," says Reed Engle, former cultural resource specialist with the Shenandoah National Park.

Gas sales and taxes and the boon of increased tourism gave the national park idea a thumbs up from businessmen.

"There wouldn't have been a park without cars," says Engle. "It was all about the auto culture."

First steps

President Calvin Coolidge authorized the park in 1926. But it was his successor, Herbert Hoover, who created the ultimate green light for the emerging car culture: a mountaintop road.

Hoover, a trout-fishing fan, had already established a "summer White House" on the headwaters of the Rapidan River on land that would become part of the park. In 1931, construction began on the 105-mile Skyline Drive along the ridge from Front Royal to Rockfish Gap.

"These mountains are made for a road," Hoover reportedly told a friend as the two rode horseback, "and everybody ought to have a chance to get the views from here."

Construction began using local farmers paid by federal drought-relief funds. In 1933, FDR, eager to put unemployed Americans to work, allotted $10 million for the Civilian Conservation Corps, and secured the construction of the park in the middle of the Depression.

The only problem? Unlike the sparsely inhabited wildernesses of the west, around 500 families lived on the targeted land, and the human presence was a problem in an area where nature was supposed to be the theme.

At the same time as Jews were being demonized in Nazi Germany, the eugenics movement had taken a firm foothold in Virginia, a state that had begun sterilizing "immoral" female citizens. (Charlottesville now has a historical marker dedicated to Carrie Buck, one of those sterilization victims.)

With that sociological backdrop, it was no great leap to portray the folks living in the mountains as backward hillbillies. Not only that, but those who wanted the park, like resort owner Pollock, made it appear that taking the residents' land and forcing them to move from their homes was doing them a big favor.

Dogpatch history

Even Edgar Allan Poe played a supporting role by contributing to the imagery of mountaineers as "fierce and uncouth" in his 1845 story, "A Tale of the Ragged Mountains." More damning to the mountain dwellers was a 1933 book called Hollow Folk. The book stereotyped Appalachian Virginians as real-life examples of the characters in the L'il Abner comic strip, shiftless yokels who eked out a subsistence existence with primitive agriculture in their own little Dogpatch.

The book portrayed the residents of Nicholson, Weakley, and Corbin hollows as having no community, government, organized religion, or any social organization outside family– not truly members of the 20th century, according to historian Audrey J. Horning.

"It was a series of sociological studies imposing Dogpatch history on the Shenandoah National Park region," Horning writes, "that succeeded in fostering widespread support for the removal and effective disenfranchising of residents."

For visuals, the government sent a photographer to Virginia in October 1935 to document the condition of the people who would be relocated. Before he left Washington, the photographer, Arthur Rothstein, met with the authors of Hollow Folk, says Richard Knox Robinson, who has made a film documentary called Rothstein's First Assignment.

"It seemed clear Rothstein picked the poorest mountain families to be photographed," says the filmmaker. "It's widely believed his images were used to justify moving people out of the park."

Robinson says that one Corbin Hollow family on whom Rothstein focused became pretty much the poster children for Hollow Folk– and for the eugenics movement. Eugenics purveyors had a tendency to identify a problem family, explains Robinson, and a large number of Corbin children ended up sterilized and institutionalized in the Virginia Colony for the Epileptic and Feebleminded in Lynchburg.

"The Corbins had a number of things against them," explains Robinson. "They were poor, had illegitimate children, a number of them were cross-eyed, and they had a distinct accent," he says. (One family member had pellagra, a dietary disease then construed by eugenicists as evidence of bad genes.)

In pre-park days before he wanted them gone, Skyland proprietor George Pollock featured the Corbins as an example of the mountain culture in a brochure, says Robinson.

"Then he said they had to be saved, and he used Corbin Hollow as an example of their poverty," says Robinson.

Those portrayals still upset Nancy Martin-Perdue, who with her late husband, Chuck Perdue, documented the history of the people displaced by the Shenandoah National Park. And she puts the blame squarely on the tourism industry.

"They were living a life that was common in the early part of the century," she says. "To take land from people considered lower class– it was a subsistence viewpoint put against the middle class who wanted to get out in nature.

"These people already were living in nature," continues Martin-Perdue. "Yet it turned into, 'We have the right to make decisions for them.' People justified taking their land and gave them very little for it."

Just because the mountain residents lived without indoor plumbing or electricity, or washed clothes by hand, doesn't mean they should be portrayed as backward, says Martin-Perdue.

Government accounts frequently referred to some of the displaced people as "squatters" because they couldn't produce convincing records showing their right to the property, even though families had been on the land for generations and had built houses and barns. Most were paid for their improvements, but some were forcibly removed with no compensation for the structures they lost.

Martin-Perdue first became aware of the agony of the exodus when she lived in Rappahannock County in the 1970s and heard neighbors recounting stories of people pushed off land their families had farmed for generations.

"Some people died of heartbreak," she says. "They just pined away. Some never recovered and were bitter the rest of their lives."

Albemarle wants in

In Albemarle, the 1920s brought attractions like Fry's Spring Beach Club and the public opening of Monticello and Michie Tavern, and Charlottesville's leading citizens leapt upon the idea of getting a piece of a national park and its ensuing tourist dollars, according to Andrew H. Myers' 1993 article, "Creation of Shenandoah National Park: Albemarle County Cultures in Conflict" in the Magazine of Albemarle County History.

Led by Skyland's Pollock, an organization called Shenandoah National Park Association was formed to raise the cash needed to buy the land for the park, and local businessman Hollis Rinehart was its treasurer.

Rinehart was joined in the fundraising effort by fellow charter members of the then-new Farmington Country Club, Percy H. Faulconer, a construction magnate, and James H. Lindsay, publisher and editor of the the Daily Progress. Chamber of Commerce president Thomas Farrar and UVA president Edwin Alderman also helped raise Albemarle's goal of $61,000, according to Myers.

Myers contends that the perception of the mountain people as "backwoods squatters" was perpetuated by the Daily Progress, and the newspaper featured them in articles not merely as impoverished, but as murderers and moonshiners.

In the hollows of western Albemarle, much like Madison, there were poor people, but there were also some well-off farmers. Because of intervening ridges including Cedar and Pasture Fence mountains, Bucks Elbow, and Cherry, Currant and Pigeon Top mountains, it was easier for residents of Browns Gap, Via's Gap, and Blackwell's Hollow to buy their supplies and take their cattle west to Augusta County.

"The geography served to isolate them somewhat from the modern world of the 1920s," writes Myers– and from the movers and shakers in Charlottesville.

Thirty-nine Albemarle land owners– including the City of Charlottesville– saw their property condemned. And despite the portrayal of mountaineers as illiterate and inept, at least one had the wherewithal to sue.

Business-minded orchardist Robert H. Via filed suit in 1934 to stop the eminent domain seizure, arguing that the state of Virginia had no constitutional right to take his 152 acres in the Moormans River Valley and give it to the federal government. Via was the only person to sue, and he did not prevail.

However, as enthusiastic as the state's park boosters were, they were unable to raise the cash needed to buy the 521,000 acres originally envisioned, and the size of the park was reduced twice. The park opened in 1936 with 176,429 acres and now comprises about 197,000 acres.

It was the cost factor that kept places such as Bucks Elbow Mountain and Charlottesville's Sugar Hollow Reservoir out of the Shenandoah National Park.

"The more fertile lowland tracts cost an average of $5 per acre and had little scenic value," writes Myers. "The more spectacular cliffs, on the other hand, cost $1 per acre."

Cost also was the reason that the Scott family enclave, Royal Orchard, avoided becoming part of the park. But in that case, influence helped as well.

According to legend, Royal Orchard produced the Albemarle Pippin apples beloved by Queen Victoria, hence the "royal" moniker. Beginning in 1903, according to Reed Engle's account, Frederic W. and Elisabeth Strother Scott of Scott Stadium and Scott & Stringfellow stock brokerage fame, bought the orchard, built a castle, and expanded the property to 4,000 acres.

So prominent were the Scotts and so vast was their tract that Skyline Drive was destined to end at Jarmans Gap rather than its current southern terminus at Rockfish Gap. But in 1933, President Roosevelt approved another ridge-hugging road, the Blue Ridge Parkway, and he wanted the two to connect.

"One of the cute stories has to do with the location of Skyline Drive," recalls Frederic Scott's grandson, Buford Scott. "Grandfather found it was to come down on the east side of Afton Mountain– about 50 yards from our house. He invited [Secretary of the Interior] Harold Ickes to stay at Royal Orchard. Mr. Ickes asked where Skyline would go."

Before long, the path of road was moved to the west and out of Royal Orchard's viewshed, and in return grandfather Scott donated a scenic easement of 400 feet on either side of the Drive.

"Ink is really cheap," chuckles Scott about the redrawn map.

Less affluent park-bordering landowners didn't fare as well. The park and Skyline Drive blocked historic paths– such as Jarmans Gap Road– that had long linked Albemarle farmers to the markets and rail lines of the Shenandoah Valley.

"Rather than bringing civilization to an isolated enclave," writes Myers, "the park had cut vital links to Augusta County and disrupted the local economy."

Litigant Bob Via left Virginia and moved to a farm near Hershey, Pennsylvania. Via never returned to Virginia, and according to historian Robert A. Yingst, he never cashed the $3,230 check he received for Via Mountain, considering it not even close to compensating for the loss of his family's land.

Children of the Shenandoah

In the 1990s, 60 years after their parents and grandparents had been kicked off their land, some of the descendants had had enough of seeing their people portrayed as slack-jawed yokels. One thing that really added insult to injury was the 20-minute film shown at the Byrd Visitors Center called The Gift.

Not only did the title of the the 1960s-era documentary suggest that the former residents had decided to generously donate their family lands to the National Park Service, but when it did mention the residents, says former cultural resource specialist Engle (under whose tenure The Gift was retired), "They were all treated like Snuffy Smith with a long rifle and a bottle of moonshine."

Engle also notes that early park planners often burned down buildings or let them fall apart due to neglect.

"Shenandoah was considered a natural park," says Engle. "There was no sense there was a cultural element. We ripped down things that are irreplaceable: taverns, mills. It was atrocious."

Yet in some ways today, that natural respite from suburban sprawl just 60 miles from Washington has gained new value. In 1935, Engle notes, that there were hardly any deer and no bear.

The park is a huge stopover for migrating birds. "It serves as a breeding ground," says Engle. "It's a critical open space– an incredibly important corridor."

One marvel that hasn't changed much since opening day is the 105-mile drive built along the top of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

"I don't see how environmentally that would ever happen today," says Engle. "I'm not sure economically it would ever happen."

Jimmy Brown is one of the founders of Children of the Shenandoah; his great-grandfather was Old Rag postmaster William Austin Brown.

"The park did not do a good job of public relations," says Brown. "In 1933, there was a concerted effort to picture the residents as unwashed, uneducated heathens that needed to be saved."

Stories of people being dragged from their homes or forced to watch their houses burn linger. Most notably was the picture of a pregnant woman named Lessie Cave Jenkins hauled off by two deputies because she and husband Walker Jenkins, deemed squatters, refused to leave without compensation for the house, barn, fences, and other improvements on their farm.

Could it happen again? Could the government take land it desires using eminent domain and portray the residents as much better off removed from their homes?

Ask someone who used to live in Vinegar Hill. A largely African-American community in Charlottesville, Vinegar Hill was flattened in the 1960s in the name of urban renewal and is now known for a cluster of parking lots and suburban-style buildings including a Wendy's, a McDonald's, and a Staples.

"It still happens today," says Nancy Martin-Perdue, noting sarcastically that places like Vinegar Hill get redeveloped "for the benefit of a group of people who have superior needs and superior claims."

It-could-have-been-handled-better is a sentiment that has been repeatedly expressed by the Children of the Shenandoah, a now-defunct group of evictee descendants that banded together to correct the historical record. Because the story of their predecessors' ouster no longer bears the taint of government spin, the group hasn't met in about five years.

"Many of the [Children of the Shenandoah] I met love the park," says Engle. "They realize it would be ski resorts and condos like in West Virginia with no public access at all."

'I love the park," echoes Children charter member Brown. "I just wish it could have been formed in a different manner."

Brown still returns to his family's old homeplace and cleans the spring. He keeps track of the many unmarked cemeteries throughout the area, and says the hiking trail to Old Rag Mountain goes through one of them. Brown, 55, speaks nostalgically about a life he never experienced, but about which he's often heard.

"No one ever talked about being hungry. No one ever talked about being cold," says Brown. "They didn't have a lot of cash, but they didn't need a lot of cash.

"They may have been poor people, but compare them to the people in the soup lines in the Depression," continues Brown. "They grew everything they needed except coffee and sugar.

"Everyone talks about how they loved living up there– how pleasant it was. It was cool in the summer. Everyone knew everyone and helped each other out. No one locked their doors."

He pauses. "When you move out, you always remember the best parts."

Walking under a thick canopy of hardwood trees along the rocky Hughes River as the water gurgles and the temperature seems to be at least ten degrees cooler than in Charlottesville, it seems like this has always been a natural preserve.

"Unless you know... " says Brown. "Thousands of people hike through and don't know what was there."

Correction 7/31/2013: U.S. Senator Harry Byrd's office during massive resistance was incorrectly identified in the original version.

20 comments

Outstanding read. Thank you.

Great job Lisa!

My understanding is that my great-grandfather's family was removed from Hensley hollow. I really enjoyed reading your article.

This is a well told and often told story. Truth is, some of the stereotypes of backward hill-billies are true, but that doesn't diminish the scope of injustice done to these folks. Many blame the federal govt. for it, but the reality is the state was anxious to round up land for "donation" so they could put a feather in their cap in the form of a national park.

Land ownership was a peculiar thing in Virginia and much of the south, in that much land title passed down from royal grants given in colonial times. Land unsuited for plantation type agriculture was left to languish and was settled by lower caste people who had no connections to the gentry, and like much land elsewhere in the states was simply settled by occupying it or "squatting" on it if you want to use a pejorative word. Being unworldly, the "hollow people" had no clue about getting lawyers and asserting their rights of adverse possession under which they could have obtained true title to land their families had occupied unmolested for generations, but instead they were victimized by the sort of criminal conspiracy often directed at the unconnected, particularly in the old south which Virginia in the thirties was.

It's interesting that people in Eastern Europe who lost lands to the communists after the war, were able to reclaim their lands after those governments fell, and that dispossessed Jews also reclaimed properties confiscated by the Nazis and their lackeys. That would never happen in this country (and I think some descendants have made attempts, though I cannot cite chapter and verse). So in a sense the conspiracy is ongoing even in the present.

I have known a number of people who are descendants of people kicked off their land and rendered society's outcasts in the process. They keep alive the family stories of lands their grandparents owned, of self sufficient farms stolen from them by arrogant officials..

Congratulations and thank you on an excellent article.

Just as an added note. More land was taken in Madison county than any other yet Madison was the only county not given

access to the Park by a maintained road.

Lisa,

Great job. I am pleased you took this assignment serious and I appreciate the great job

you have done. Good stories and good facts. Keep up the good work

Jim Lillard

This was an excellent article. As someone who grew up in Rappahannock County and who knew or were related to families displaced I am always happy to see stories on this topic.

For those interested in the history of the formation of the park, I recommend reading The Undying Past of Shenandoah National Park by Darwin Lambert.

Also there are some PBS videos about the park and its origin that attempt to clear up some of the old misconceptions. From the Hills and Hollows came out in 2002 and while dealing with a wider range of topics pertaining to the Blue Ridge and its settlement does devote considerable time to the displacement of park residents. There is a new one out also called The Iris Still Blooms. The title refers to the fact that flowers planted by former park residents were still in evidence look after they and their houses were gone.

It was good to make a comparison to the Vinegar Hill displacement. For that matter the argument used to support removal of the mountain people was also used to defend bringing African slaves to America. That they had no culture, no morals, no religion, were just backward savages who would benefit from being taken to white Christian civilization.

It is certainly true that they were not all impoverished. A family into whom a cousin of mine married in 1943 owned hundreds of acres of land and even had people working for them. But the state still took it.

It is wonderful to have the park. Its only too bad that its acquisition was not handled differently as far as the people were concerned.

It is too bad that the Children of Shenandoah appears to have folded. In 2002 and 2003 I attended the annual picnics they held in the park In Greene County , and met or re-connected with some fine people. Some were people I had not seen since my school days in the county.

This article is propaganda to make sure people remember the benefits of elite-sponsored eugenics in the name of protecting the environment. Every time you think how horrible and corrupt government land grabs are you can look to the west and say "it's for the greater good". The heirs to the elite eugenicists of the early 20th century have an end game of shutting off 90% of the planet not just to human habitation but to any human activity after reducing the worlds population to 500 million through GMO food sterilization, vaccine induced death, fluoride and bpa induced sterility and feminizing of human males, and all sorts of other horrible things that they know they can do openly to kill and sterilize you because you're too much of a coward (and too busy working as their slave) face it and do something to stop them. Eugenics is being carried out in modern times against all of us on a scale that rivals the forced tube tying of that generation in some ways and in other ways makes that look tame. But as long as you understand it's to save the earth you should appreciate what these Nazi-esque (and in many cases, real Nazi) control freaks have done.

Teddy Roosevelt started the national park idea so that he could blow away more bison, blow away more ivory billed woodpeckers, blow away more lions tigers and bears, and put their taxidermied heads on his wall. The parks were also created as collateral for the debts the elite planned to rack up on the nation's tab, when you see a sign that says "UNESCO World Heritage Site" it means it's no longer the sole property of the nation or state it is located in. Now it belongs to the New World Order.

A hundred years or so into the future, the year 2111, almost the entire United States is now a national park, only a few hundred million people inhabit the planet, wildlife is thriving everywhere, endangered species of flora and fauna are abundant, the water and air are pure and non acidic once again because the elite had the foresight and fortitude to do what needed to be done: Kill and sterilize billions of people. The few remaining humans will read historical signs at the parks saying "Humanity was out of control and destined to destroy itself if something wasn't done to reduce population. Our great leaders saw this problem arising, and as sad as it is that we had to exterminate billions upon billions of human beings, we now live in a world in harmony with nature instead of at war with it, and it is good." And the people reading the signs will feel much the same way you feel reading this article. The only problem is this: Once you unlock a genetic lock, you can't reverse it. In other words, the same eugenicists who developed Genetically Modified Organisms to kill and sterilize humans while hoarding non GMO seed vaults in the Arctic didn't have the forsight to realize that the GMO's would inevitably taint all life on the planet through cross pollination and cross breeding with the God created genetic line. The same ones claiming to save the Earth are destroying it by the very same mechanism they employ in the name of saving it.

That's why there are all those strange globules on oak trees. No, they didn't engineer the oak trees. The genetic key to unlock and enter the oak tree genetics came from a GMO soybean plant, or a GMO maize, etc. God made a barrier between soybeans and oak trees intermingling their genetics, and the heirs to the eugenicists, in the name of saving the earth by reducing human population, wanted to sterilize people through the food, so they tore down that barrier between soybeans and oak trees (just for example) because it was necessary in order to engineer a maize plant that would sterilize human beings when they ate it as children. Of course, we won't realize that the kids who grew up eating GMO corn are sterile until they try to have kids, and by then it will be too late, just like it will be too late to save all life on the planet from GMO contamination. We were too busy feeling good about saving the environment and demonizing patriots who weren't in line with the propaganda to save the environment to save the environment. Ha ha ha!

It appears the tinfoil hat crowd has weighed in at the last; why this article piqued their interest...who knows?

Because it's about eugenics, which is being carried out against you and your family. Ha ha!

Once again an interesting thread, one about a subject that has deep personal meaning to some of us, has been hijacked by trolls!

Feel good stories about control-freak eugenics-based land grabs carried out in the name of protecting the environment by the same government that's destroying it have a deep personal meaning to me too. Glad we share something in common. Who are you calling a troll, anyway?

@John and Imagine: You're supposed take only 1 tab at a time. They're small yes but the effect is pronounced.

Half-wit.

@Angel Eyes: Out of the more than 500 families that were removed from the mountains, almost all of them either rented or owned their land. There were a total of 7 families that were squatters.

This colossal crime against the people of the Blue Ridge cannot be pinned on solely the federal and/or state government. When you look at who was involved in the acquisition of land, the lobbying, and who was connected to the copper companies, it is a tangled spider web of who's who from the boards of directors of the Fortune 500.

Great article! I very much enjoyed it.

Very nice article. My grandparents were among the ones to be "swindled".

This brought back memories of many stories told by them and others about their lives.

Thanks.

The Perdues were part of the anthropology department at UVA when I first met them and learned more about the initiation of the park. A sad story, and not the least of it was the demeaning of the people who lived there. But the governmental power to use eminent domain for important public purposes, although it can be abused, is also vital to the common good. All power, public and private, can be abused, but the possibility of abuse, does not mean that the power itself should be eliminated. I think that Shenandoah National Park is a jewel; I enjoy its streams, wildlife, and trails. Thank you Lisa and the Perdues also. Let's not let this story blind us to the need to protect and value the park, today. The gateways to the park, and, perhaps,. even some additions (including cultural properties) should not be dismissed, because of some abuses or injustices in its founding.