The Tale of Colin and Gillian

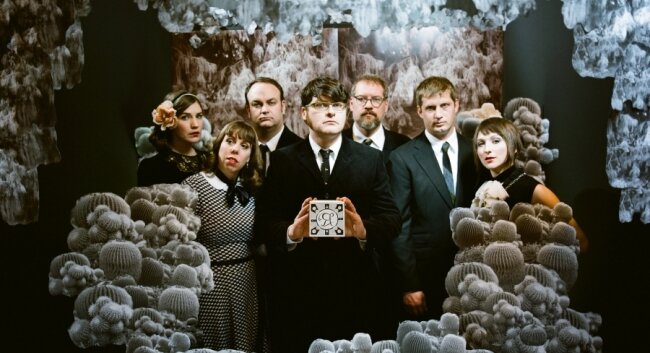

The Decemberists became arguably the most intellectually intimidating art-rockers of the new century thus far largely because they spent nearly a decade writing increasingly complex music immediately following their 2002 debut, moving from their twee roots to a metal-influenced 18-minute track based on Irish mythology and 2009's The Hazards of Love, a lengthy and bizarre rock opera set in a fantasy world.

When they announced that their newest album would be a simple, country-influenced affair, many fans were skeptical of such a radical shift in direction. But although The King Is Dead looked at first like it might be the first deep calming breath of a simpler folk period, it actually turned out to be closer to their usual fare than anticipated.

More than anything sonic, one of the biggest changes was to the content: obscure twists and exotic settings gave way to more traditional Americana. We find ourselves in Nebraska rather than inside a whale or at the Spanish royal court. This moves the band from historical and geographical wanderings to a more immediate connection to American folk – not back to Woody Guthrie, but at least to Bruce Springsteen.

This new folk sensibility is less a change in thinking than it is a change of location. The narratives on concept records like The Tain and The Crane Wife show a fascination with folk stories, just not American ones. Moreover, the album still contains Colin Meloy's trademark vocabulary and hyperliteracy. The writing works here, but references to historical business mogul Hetty Green and the David Foster Wallace novel Infinite Jest within a few lines of each other don't make for very rootsy fare.

The sea shanties of albums past are gone. Instead, the guest appearances by guitarist David Rawlings and folk queen Gillian Welch, the latter of whom appears on seven tracks, speed "Dear Avery" right along into Nashville. The fiddling on "All Arise!" moves the album further into country territory, and the ghost of Uncle Tupelo haunts "June Hymn." The band doesn't quite lose itself in these sounds, though: Peter Buck's appearances only enable the R.E.M. influences that were already there, and "This Is Why We Fight" wouldn't have sounded out of place on 2005's Picaresque. They're exploring new territory, but cautiously.

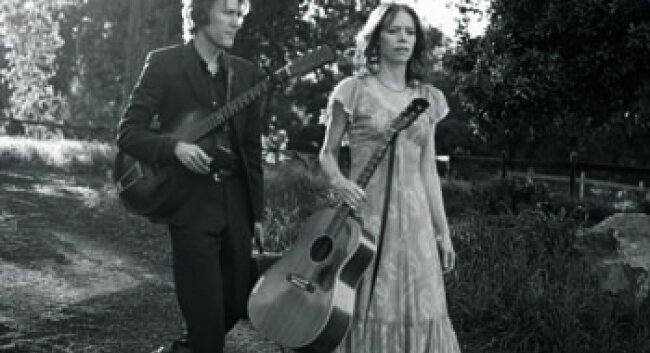

Collaborator Welch, who will be appearing at the Paramount Theater on August 18, provides the album with its country twang and harmonies, but her new album The Harrow & the Harvest is an interesting aesthetic contrast to the newly reborn Decemberists. It's not as focused on replicating old-timey mountain music as the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack, but it still stays firmly grounded in tradition, even if there are a few nods to L.A. country-rock. She and Rawlings use simpler arrangements, gospel influences, and lots of vocal harmonies.

Welch also acknowledges American folk music more explicitly than Meloy does. “Scarlet Town” plays with your expectations of a murder ballad. The banjo-led “Hard Times”, echoing Stephen Foster and Skip James, references “Camptown Races” and has an unnamed character lamenting troubling times. “Six White Horses” uses a line from “Comin' Round The Mountain” to meditate on death, a closer match to its roots as a spiritual number.

Oddly, the presence of ultra-traditionalists Welch and Rawlings actually highlights the continuity that connects the Decemberists' supposedly dramatic change to their rock and roll origins. Consistency gives fans a centering element from which to reach out to the actual changes, and the band's ability to hold steady even as they experiment demonstrates a compelling artistic strength. This is the difference between "tradition" as a guiding principle and "traditional" as an aesthetic. But as these artists show, either approach can have memorable results.

The Decemberists perform at the nTelos Wireless Pavilion on 8/3; tickets cost $35 and the show starts at 7pm. Gillian Welch performs at the Paramount Theater on 8/18; tickets cost $32 and the show starts at 8pm.