>> Back to The HooK front page

COVER- How UVA turns its back on rape

Published November 11, 2004 in issue 0345 of the Hook

By COURTENEY STUART

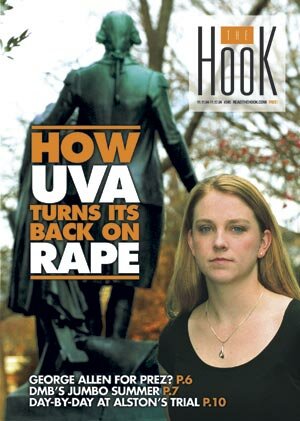

UVA has a system to deal with rape among students. A group meets, takes testimony, and issues rulings-- all in secret. This clandestine process, combined with what one victim brands a "slap on the wrist" for rapists, has left several victims wondering who the policy was designed to protect. Among those wondering is 21-year-old Annie Hylton.

"It's a false community of trust," says Hylton, a fourth year who claims she was raped by a fellow student during her first year at the University. Although she says her alleged attacker was found guilty by the secret committee-- officially known as the Sexual Assault Board-- he continued to walk the hallowed Grounds designed by Thomas Jefferson until his graduation in 2003.

"He was banned from the first year dining hall and from the Aquatic and Fitness Center," Hylton says of the perpetrator's punishment, "and he had to attend counseling." The University also imposed a restraining order prohibiting him from contacting Hylton.

By going public, Hylton becomes a rarity in American discourse: a sexual assault victim who isn't hiding behind a cloak of anonymity. She says she's putting her name and story before the public with the hope that she will help others.

But by speaking out, Hylton might find herself facing charges of breaching the secrecy rules and wind up being punished more severely than her alleged attacker.

Outrage: lots of rape and little punishment

One of the most bitter ironies for UVA rape victims is that the school seems to reserve its harshest penalties not for sexual predators, but for students who violate the Honor Code, an antebellum proscription against lying, cheating, and stealing. Honor offenses can include such things as copying a classmate's French homework or stealing a bicycle. Honor violators draw just one penalty: immediate and permanent expulsion.

In the past three years, that single sanction has sent 38 UVA students packing, according to Honor Committee data.

In the same span, 60 UVA students reported they'd been sexually assaulted, many by fellow students. Yet, according to various sources in the UVA administration, not one sexual offender has been expelled or even suspended from the school in the past five years, a fact that has outraged many people-- not just victims and their families.

"That someone can be found guilty of rape and remain at UVA is unacceptable," says Kyle Boynton, president of Sexual Assault Peer Advocacy, a group of UVA students trained to assist victims of sexual assault. "UVA administration has a long way to go to reach a good system."

UVA may get some help revising its policies. Hylton has filed a complaint against UVA with the Department of Education, which requires universities to make public the dates and results of all sexual assault hearings.

Hylton says the school has not complied. Her particular story is not unusual-- though her decision to go public and to file a civil suit against her attacker is.

Party to a lawsuit

In the $1.85 million suit she filed in Charlottesville Circuit Court two years after the incident, Hylton reveals allegations of the evening that changed her life. What follows is her side of the story.

Her first semester at UVA was winding down when a friend asked if she'd like to go on a double date to a fraternity function. Though Hylton hadn't met her prospective date-- a third year named Matthew Hamilton-- she says she looked forward to the evening of December 8, 2001.

The two couples had dinner downtown. While Hylton says the early part of the evening was "fine," she alleges that even at the restaurant, things began to go wrong.

Hamilton "repeatedly offered" to obtain alcoholic drinks for then 18-year-old Hylton. She "repeatedly declined," but Hamilton continued to bring them. Hylton drank only "a small amount," the suit states, "not enough so that it would have affected her."

Later on, her recollection becomes sketchy. At the party at the Delta Tau Delta fraternity, where both women's dates were members, Hylton "became very ill and vomited a number of times."

Her nausea continued, and while "she was aware of some things that happened... she was not able to function and felt mentally and physically impaired," according to her suit.

If this sounds like a classic description of the effects of so-called "date-rape drugs," Hylton stops short of offering that theory.

"We're not making any claims at this point," says her lawyer, Ed Wayland. "We're hoping to get an explanation during the course of the investigation."

At one point, Hylton became aware that she was wearing a t-shirt and that she was in Mr. Hamilton's bed. "Mr. Hamilton was not in the bed, but Ms. Hylton was aware that he and one or more other people were in the room."

Then she lost consciousness. When she awoke, "Mr. Hamilton was on top of her engaging in sexual intercourse."

Hylton attempted to get Hamilton to stop, the suit alleges, but he did not. "Mr. Hamilton held Ms. Hylton down, continued to touch and fondle her and attempted to resume having sexual intercourse."

Did Hylton drink more than she thought?

Hylton didn't report to a hospital until the next morning-- too late for an accurate test of her blood alcohol content or for the presence of "date rape drugs."

Medical personnel were, however, able to administer a PERK (Physical Evidence Recovery Kit), a procedure which Hylton describes as "the worst thing ever created."

To recover evidence a nurse must wet- and dry-swab every place the attacker may have touched; remove and test clothing; pluck 10 hairs from both the pubic region and the head; take close-up photographs of the victim's genital region; and apply a special dye to the genitals to determine if there is bruising or tearing.

"It's totally humiliating," says Hylton.

Veil of secrecy

Witnesses in date-rape cases are rare, and so are prosecutions. "If guys aren't stupid," says Hylton, "they'll say the sex was consensual."

Charlottesville Commonwealth's Attorney Dave Chapman says many cases do boil down to dueling "he said/she said" charges which simply aren't enough to win a court battle.

"We need to have evidence beyond a reasonable doubt," says Chapman. While legally equivalent to cases of stranger rape, date rapes, Chapman says, are far harder to prosecute. Complicating factors include alcohol consumption that, he points out, can muddle the victim's recollection. And there's often very little in the way of physical evidence-- beyond the proof that some kind of sexual contact occurred.

In April 2004, Chapman's office did prosecute a UVA date rape case. A female student, whose name the Hook has withheld, claimed that UVA second year Zachary Jesse had raped her, vaginally and anally, while she was slumped over a toilet in her apartment following a party. Jesse pleaded guilty to a lesser charge aggravated sexual battery and served three months in jail. As part of the plea, he agreed to withdraw from UVA for two years, until his victim graduates.

Chapman's office declined to press charges in Hylton's case, so she decided to seek justice through UVA channels. She requested a hearing before the Sexual Assault Board, a specialized offshoot of the University Judiciary Committee, and was granted a hearing in March 2002, three months after the alleged assault.

The experience, she says, was "devastating." Accompanied by a lawyer and an "advocate"-- in her case, a representative from UVA's Women's Center-- Hylton came face to face with Matthew Hamilton.

Before the Board, both she and Hamilton offered their versions of the story. Each was allowed to submit questions that board members then read aloud.

The hearing lasted from 5pm until 11pm, Hylton says, when the board adjourned to deliberate. Two hours later-- at nearly 1am-- Board members returned and announced that they would recess for two weeks before completing their deliberations.

Hylton says she was told that all aspects of the hearing-- including her attacker's name and the outcome of the hearing-- had to remain confidential. If she revealed those details, she was warned, she could face a Judiciary Committee penalty, which can include suspension or expulsion.

At the end of two weeks, the Board returned a guilty verdict against Hamilton. But Hylton's ordeal was not over. Her attacker was allowed to remain at UVA, and she was not allowed to say a word about him.

Fear of him

For the next year and a half, Hylton says, she lived in fear of a run-in with Hamilton.

"I couldn't sleep, couldn't eat, missed classes," she recalls. "I had suicidal thoughts. I was on medication."

A member of the varsity volleyball team, Hylton says that support from her coach, Melissa Shelton, was the "only reason" she stayed at UVA.

Shelton describes Hylton as a "team leader" who has been "inspiring" to her coaches and fellow teammates.

"She's a very strong and determined young woman," says Shelton, "to not only survive what she's gone through but then to go ahead and try to make it easier for other victims to prosecute their rapists."

Hylton says despite the nearly two years of struggling, her mental state improved after Hamilton graduated in 2003. But she says her belief that he had never really been held accountable prompted her to take further action.

On December 5, 2003-- just days before the two-year statute of limitations expired-- Hylton filed suit against Hamilton in Charlottesville Circuit Court asking for nearly $2 million in compensatory and punitive damages.

"I feel like he messed with the wrong person," she says.

His Story

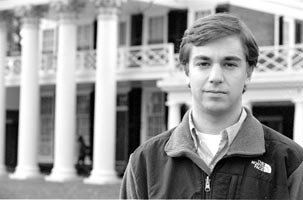

Hamilton tells a different story. Both in court filings and through his Richmond attorney, Terrence Graves, Hamilton and his attornies deny all of Hylton's material allegations-- everything from her portrayal of Hamilton's drink-offering to how she got into the t-shirt.

Hamilton's comments all came via email through his attorney, as he declined to speak directly with a reporter and refused to answer specific questions about the events of December 8, 2001.

As for Hylton's plunge into unconsciousness, Hamilton's attorneys point out that there is no evidence suggesting that any drugs, other than alcohol, played a role.

Hamilton says he was surprised at the timing of Hylton's suit because he thought she'd already realized "it had no merit."

And while Hamilton considers campus sexual offenses a "serious issue" that should be "prevented at all costs," he believes there is another type of victim who is often overlooked: those falsely accused, as he says he has been.

The effect on him and his family, he says, has been "detrimental in every way," and he believes those who "lay false sexual offending claims should be held accountable for their injurious and false accusations."

Kathryn Russell, who says she was raped by a fellow UVA student in February 2004, disputes any notion that women frequently file false claims.

FBI statistics, she says, put the number of false rape reports at roughly eight percent. Since UVA's Sexual Assault Board's conviction rate is just 50 percent, Russell says it all comes down to math.

"Forty percent of rapists at UVA get away with it," she concludes.

As a one-time defendant before the SAB, Hamilton says he believes confidentiality is necessary.

"In cases where the accused is innocent," he says, "regardless of the facts or the situation, the word 'rape' has such a negative and injurious connotation that the accused cannot help but suffer if the confidentiality requirement were lifted."

Powerful help

Revealing details of the proceedings may be injurious to defendants, but it's actually illegal for the University not to make hearing results public, and a powerful lobbying organization has stepped forward to try to force UVA to comply with federal law.

That organization is Pennsylvania-based Security on Campus, a nonprofit founded by Connie and Howard Clery in 1988, two years after their daughter, Jeanne, was brutally raped and murdered in her Lehigh University dorm room. The Clerys eventually won passage of a federal statute requiring universities to disclose information about crime on and around their campuses. The Jeanne Clery Act applies to any school that offers federal student financial aid programs.

When Dan Carter, a vice president of Security on Campus, heard Hylton's story, he filed a complaint on Hylton's behalf with the Department of Education, which enforces the law.

"The University of Virginia's sexual assault response policies and practices appear to conflict with the federal Jeanne Clery Act's requirement," he wrote, "that the accuser 'without condition' be informed of the outcome of any institutional disciplinary proceeding brought alleging a sex offense."

Carter, who will join Hylton later this month on a DatelineNBC segment investigating campus rape, says UVA's policies are unacceptable. But, he adds, the school is not alone in its mishandling of rape cases.

The Department of Education recently required Georgetown University to rewrite its sexual assault policy following a complaint from a female student who had been forced to sign a confidentiality agreement prior to a hearing before the school's sexual assault board. While UVA simply required a verbal commitment, the effect, says Carter, is the same.

Victims must be free to identify their alleged assailant, says Carter. "They need to be able to talk about the substance of their case, their experience with the process, and to disclose results."

UVA's policy, he says, is "particularly egregious" because "in the strictest interpretation, victims would not be allowed to talk to law enforcement."

A mother's anger

Annie Hylton is not the only one speaking out against the way UVA handles rape cases. Kathryn Russell's mother, Susan, is so outraged that in March she launched a website, uvavictimsofrape.com.

The response, Susan says, has been "overwhelming." More than 100 women have contacted her with their stories of being sexually assaulted at UVA.

One posted letter comes from a 2004 UVA grad who says she was raped by a UVA medical student during her senior year-- six weeks after she underwent brain surgery.

"He forced me to have anal sex with him," says this alleged victim in a phone call from her Northern Virginia home.

Despite her allegation that another woman had already filed a complaint against the same man, this woman claims that her request for a hearing was stymied by university officials.

"I feel like they turned their back when I needed them most," she says. "The whole process took so long." She eventually cancelled her planned Sexual Assault Board hearing, which was scheduled for the day after her graduation-- several months after the attack.

Kathryn Russell also believes UVA's process is grievously flawed. After her attack in February 2004, Russell says, she had to make repeated calls to Dean of Students Penny Rue's office before a hearing was scheduled. She says Rue delayed her request by, among other things, suggesting she enter mediation with her alleged attacker.

"I wanted him out of school," says Russell. "What did I have to mediate?"

Her Sexual Assault Board hearing brought her no satisfaction. After listening to hours of testimony and deliberating for three hours, the board returned a not guilty verdict against Russell's alleged attacker. The board offered no explanation, she says, nor did the school ever offer her any services after the trial.

Russell says they told the man she accused, "We believe you made a bad choice that night."

"I felt like I was drowning," she says, "the whole thing was so futile. So many months of my life, so much torture for nothing."

Her mother criticizes the training of representatives to the Board-- or lack thereof.

According to University literature, Board members receive special training, but Susan Russell's Freedom of Information Act request found that preparation to serve on the panel consists of a single session of "adjudication training."

"They don't have a good understanding of victims' psychology," she says.

Hylton agrees. She says Dean Rue also attempted to deter her from pursuing charges and characterized the Sexual Assault Board hearing process as being "about education, not punishment." Russell says Rue's first question to her daughter was, "Are you embarrassed?"

Rue did not return the Hook's call.

UVA's defense

While neither Rue nor Associate Dean of Students Shamim Sisson was available to the Hook in the days leading up to press time, Sisson explained her views in an October 18 story in UVA's student newspaper, The Cavalier Daily.

Until the 1950s, Sisson says in the article, UVA had no way to handle crimes other than honor offenses-- lying, cheating, and stealing. Sisson says the "ambiguities" in many sexual assault cases make a "single sanction" response difficult.

"There is certainly a view that some take," she says, "that if one is guilty of sexual assault-- just as if one is guilty of lying, cheating, and stealing-- that they just shouldn't be here."

On November 1, regarding the situation at Georgetown University, Sisson spoke again, this time about the DOE's requirement that Georgetown University rewrite its policy.

"Given what has transpired at Georgetown," Sisson says in the article, "we are reviewing our policy and will change it." That change should be final by the spring semester, she adds. Until then, the University will consult with lawyers should any sexual assault cases arise, to ensure that the school is in compliance with the Clery Act.

While UVA still could be punished by the Department of Education-- $27,500 is the fine per incident-- Carter, of Security on Campus, says it's unlikely the Department will levy a fine against UVA-- as long as the school brings its policies into compliance.

One way the University could be fined, Carter says, is if Hylton is charged with violating the confidentiality requirement of the Sexual Assault Board hearing. Hylton doesn't seem too concerned.

"That would be an interesting twist," she says, "if they let my rapist stay and kicked me out."

Other schools are embroiled in situations that make the threat of federal fines seem like the least of UVA's worries.

A former student is suing Ohio State University for $6 million, alleging that she was raped by a fellow student who had allegedly sexually assaulted another woman two weeks earlier. By failing to adhere to its own policy to temporarily oust students accused of such crimes until after a hearing, Ohio State, the suit alleges, put the health and safety of its students at risk.

And that, says Hylton, is the bottom line. She and others say they would like to see UVA create policies that protect women-- and make rape less common. The first step is to get people talking.

"We should spend the same energy looking inward at student victims who are afraid to tell their friends what happened," says Claire Kaplan, coordinator of sexual assault education at UVA Women's Center. "There is still a culture of shame."

Kathryn Russell, however, says she thinks it's less about shame and more about fear-- particularly fear of coming face to face with their rapists.

That fear, Russell says, won't go away until women believe there is a chance their attackers will be punished-- a satisfaction she may never know.

"It's harder to deal with the fact that I got no justice than that I was raped," says Russell. "The larger trauma is the no justice-- that's what I have to live with."

Hylton hopes her activism and her lawsuit-- which goes to trial in Charlottesville next August-- will not only give her peace to move on with her life, but also will give other victims the strength to come forward.

"If I help one other woman with this," she says, "it will have all been worth it."

"I feel like he messed with the wrong person," says Hylton.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Following her alleged assault, Hylton lived in fear of a run-in with Matthew Hamilton. She had trouble sleeping and eating and at several points contemplated suicide.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Matthew Hamilton in a first-year photograph.

"That someone can be found guilty of rape and remain at the University is unacceptable," says Kyle Boynton, president of UVA's Sexual Assault Peer Advocacy.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Matthew Hamilton in a first year photograph.

Jeanne Clery was brutally raped and murdered in her Lehigh University dorm room in 1986. Her parents founded the nonprofit organization Security on Campus in her memory.

PHOTO COURTESY SECURITY ON CAMPUS

Susan Russell started the uvavictimsofrape.com website to try to bring about change at the university. She says her daughter Kathryn did not receive support from UVA administration during her ordeal.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#

>> Back to The HooK front page

|