Controversial constitutionalist: 30 years of defending the people

In the corner is a cardboard stand-up of James Dean– and another of the Beatles in a phone booth. Toy skeletons are all over the place, as well as artwork that hints of a disturbing vision.

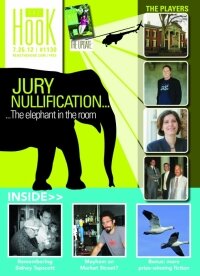

"Most people are horrified when they come in my office," says constitutional gadfly John Whitehead, whose Albemarle-based, civil liberties-defending nonprofit is celebrating its 30th birthday.

"They haven't fired me yet," jokes Whitehead. In 1982, he and his late wife Carol sank their $200 life savings into founding the Rutherford Institute. His first office was in his furniture-less rec room in the basement of his house near Manassas.

He'd been working with the ACLU in college. "One area I couldn't get the ACLU to do was religious cases," he recalls. "I started with that stuff."

He still remembers one of his earliest cases representing a family of pig farmers in Michigan who were home-schooling their children, and the father was arrested. "It was the first home-schooling case," he says, "and we won."

Whitehead attended the University of Arkansas ("the only school I could get in"), where he got his undergrad and law degrees– and crossed paths with Bill Clinton. A later encounter put Whitehead on the map after he decided to represent Paula Jones in her lawsuit against then-President Clinton for sexual harassment in 1997.

Hillary Clinton called the allegations about her husband a "right-wing conspiracy," which Whitehead shrugs off. "That was White House spin," he says.

But some still see the Rutherford Institute as a more conservative version of the ACLU.

"I've been called liberal, conservative, libertarian," he says. "I'm not any of them."

What he seems to love is freedom– even freedom in the hands or mouths of the hatefuls. Whitehead tells how he helped Margie Phelps of Westboro Baptist Church, best known for showing up at the funerals of American soldiers with signs saying,"God hates fags." Whitehead coached her in moot court before her appearance before the Supreme Court, which upheld their First Amendment right to spew hateful invective.

"Fag-lovers like you can take it up the butt," Whitehead recalls Phelps saying to him.

Despite that, "I felt good about the Phelps case," he says. "They won– even though they're reprehensible."

And that's perhaps the biggest misperception people have about Whitehead– that he shares the views of his clients. That, in turn, can affect fundraising, which has always been a problem, he says, particularly after he took the Jones case.

"I think because of the high-profile nature of the Paula Jones case, people assume John is motivated by a political agenda," says Josh Wheeler, president of the Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression.

"In my experience," says Wheeler, "that's completely inaccurate. What I've found to be his guiding principle is his concern for the underdog. The Bill of Rights, after all, stands for the rights of the individual.

So what informs this passion for justice?

"I take the Sermon on the Mount very seriously," answers Whitehead. "Blessed are the meek..."

That sermon also was central to the Christian beliefs of Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, whom Whitehead cites as an influence– as did Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

"My basic philosophy is I'm here to help people," says Whitehead. "I won't kill insects or animals." Needless to say, he's a vegetarian.

"This sense of people suffering and not getting help... " says Nisha Whitehead of her husband. "He's there to stand in the gap when everyone turns their back."

The downside to such altruism, acknowledges Nisha Whitehead, is that John has a hard time saying no. He even has a sign with "no" on it sitting on his desk from his first employee, who realized her boss' propensity to take on too much.

"He's always accessible," says Nisha. "In his mind, he can't say no. Sometimes it's 10 o'clock at night, and I want to say no."

One thing John Whitehead has proved quite adept at is finding attorneys all over the country to take on Rutherford cases– for free.

"Always when I meet someone, I ask if they'd do a free case," says Whitehead, who says there are many ways to put together a stable of attorneys. Facebook is one. The Rutherford Institute puts out press releases about the cases they're representing, which are often picked up in the media.

"Lawyers see them and contact me and say to let them know if we need help on a case," says Whitehead. And larger law firms do a certain amount of pro bono work.

"A lot of lawyers are doing really boring work," Whitehead explains. And there's one other reason: "They believe in it. And in 30 years, you build up a number of friends."

At age 66, Whitehead shows no sign of slowing down. The prolific author of 30 books says he has four more in the works, including a graphic novel. Not too surprisingly, it's about kids in a school feeling oppressed and standing up for their rights– and then the principal morphs into a praying mantis.

Thanks to industrious interns, he's also resurrecting an online version of Gadfly, the award-winning magazine from the late '90s on "culture that matters," for which Whitehead contributed articles on topics ranging from the Beatles to Blade Runner.

He's got an art show coming up in September, and his office is littered with watercolors. In one, a man is becoming a machine, which seems symbolic of Whitehead's warnings about technology and its erosion of privacy and the Fourth Amendment– only his paintings use lots of glitter.

Another upcoming project is a TV show that will broadcast once a week from a virtual studio. Whitehead credits WINA's Coy Barefoot with the idea and with letting him know how cheaply it can be done.

Mostly, Whitehead continues to help people whom he believes are being treated unjustly. He talks about the Arizona man who was jailed for hosting Bible study classes in his home. And he talks about Philip Cobbs, who was acquitted of possession of two pot plants last week after an armed SWAT-team-like group of police came onto his property last year without a search warrant.

Whitehead says he has no regrets about any of the cases he's taken. Well, maybe one. "I regret being in the presence of some of the people I've represented," he admits.

But that's what being a civil liberties lawyer is all about.

4 comments

"Fag-lovers like you can take it up the butt." hahahahaha

I wonder if the Phelps clan has one of those familial genetic mutations that makes them behave this way. Or are they just loathsomely evil? Nonetheless, I do believe in their civil liberties. Though they don't believe in mine.

"Fag-lovers like you can take it up the butt,"

Good little christian behavior

He likes Bill Clinton. He admitted it. End of debate.