COVER- Trickling away: A dam develops amid missed chances

The rush for a new dam was prompted by the lower Ragged Mountain dam's spillway, a structure whose vulnerability in a big flood could be fixed for $2.8-4.6 million. PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

With not a penny budgeted for dredging, the complete siltation of the Rivanna Reservoir is no longer a matter of "if" but "when." And information is starting to emerge that our local waterworks officials, having paid (and still paying) millions to an engineering firm that may have overestimated the cost of dredging, have already missed several opportunities to fix a broken dam and solve our future supply problems. Now, water customers are looking at buying a hotly debated reservoir straddling an Interstate highway and spending millions for the power to pump water nearly 10 miles across the county.

Rivanna Water & Sewer Authority chief Tom Frederick says his controversial $143 million dam construction plan is necessary because state regulators have demanded a fix for the aging dual-lake Ragged Mountain reservoir system. Yet the Authority's own documents indicate that it has known since 2003 that the dam can be repaired for as little as $2.8 million.

That's about equal to the money the Authority has already spent on studies and engineering reports from a single firm called Gannett Fleming– the company that claimed that dredging the silt-clogged Rivanna Reservoir back to its original capacity could cost $145 million.

Fix the Ragged Mountain dams?

The problem with the Ragged Mountain dam was first spotted in 1978 when a federally funded safety study found that both Ragged Mountain dams had deficiencies that could lead to catastrophic collapse in the event of what meteorologists call a PMF, or probable maximum flood. A PMF begins with a rainfall deluge: 28 inches in six hours or 37 inches in 24 hours, according to state climatologist Jerry Stenger. Such rainfalls are almost unheard of anywhere in the world– except in 1969 when parts of Nelson County received what may have been a world-record rainfall from remnants of Hurricane Camille.

According to the Authority's 2003 report, the main dam is structurally sound. But it wouldn't be in a flood.

The federal government has declared that structures the size of the two Ragged Mountain dams must survive a PMF. The 2003 feasibility study found that the upper dam's spillway could handle a flood just 10 percent the size of a PMF; the lower dam's spillway did a little better: it would still be standing after 25 percent of a PMF.

Unless repairs are made, a full-blown PMF like Camille would mean the dams would be overtopped by up to 4.68 feet of water for up to 12 hours– if they lasted that long. These fears led Virginia's division of Dam Safety to put the dams on "conditional" permit status.

Opponents of a hasty, knee-jerk response rapidly took aim.

"It is not in the public's best interest to rush through comprehensive community water-supply planning based on this single issue," wrote Jeff Werner of the Piedmont Environmental Council*. "An extension must be requested."

Werner's March 2005 letter was signed by 17 Central Virginia environmental leaders worried that the Authority was making a mistake by rushing to respond to the State's findings. The signees reminded Mayor David Brown and Supe chair Dennis Rooker that they ultimately hold community leadership positions and blasted the state's conditional permit as "an artificial deadline" and an "artificial crisis."

But today, many of those 17 leaders– such as longtime Moormans River fan John Martin– support the mega-Ragged Mountain/pipeline proposal. Others, such as Rich Collins– now part of a new group calling for a second opinion on dredging– do not.

Collins' group, Citizens for a Sustainable Water Supply, has recently drawn attention to the environmental damage the plan would cause: over 133 acres of forest in the Ragged Mountain natural area will be clear-cut to create one giant reservoir that will eventually become the area's lead water source– even though one end of it will lap against the embankments of Interstate 64 and actually lie– thanks to a new culvert– under the four-lane highway.

Fixing the dam

The 2003 "Feasibility Study for Upgrading the Ragged Mountain Dams" proposed that any rehab of the complex should include breaching the upper dam– on the theory that there was no way to fix its spillway. The good news from the 2003 study is that the lower dam, the one left to carry the weight of all floods, already– even though it was built in 1908– meets the modern stability standards set by the Army Corps of Engineers.

The study outlined a variety of fixes to enable the dam to handle a PMF, including an armored buttress ($2.8-3.13 million) or a new side-channel spillway ($4.14-4.56 million).

However, the report appears to favor a third option: a "roller-compacted concrete buttress." Essentially, this is a giant sheet of concrete across the downstream face of the dam so that floodwaters– as they do at the Rivanna and Sugar Hollow Reservoirs– would roll harmlessly over the top instead of cutting into the earthen buttress that now covers the original granite and concrete structure. At $3.48 million, this option falls in the middle of the cost estimates, but unlike the other two, it has a 100-year expected life span, twice those of the other two.

Frederick contends that flooding the Ragged Mountain area, now a 980-acre park owned by the City of Charlottesville, is the region's best opportunity to provide a large enough water storage facility for all future needs. Repairing Ragged Mountain now, he says in an interview, would be "just throw-away money." Critics of his plan, however, point out that roughly one-third of the capacity of an expanded Ragged Mountain system would be simply to make up for capacity that's being lost at the Rivanna Reservoir by the Authority's refusal to dredge.

Albemarle almost asked

Three years ago, Albemarle supe Sally Thomas was so frustrated with the dredging information Frederick's Authority was providing that she proffered an official resolution prodding the Authority try harder. Introduced the night of November 8, 2004, her resolution cited the example of Decatur, Illinois, which had embarked on a reservoir dredging project.

"Elected officials in that community decided not to let their lake die," said the proposed Resolution, which would have demanded that the Authority– as well as the County's own planning, engineering, and watershed protection departments– "investigate more thoroughly."

Thomas also feared the Authority was missing obvious opportunities including "finding markets for the dredged materials"– i.e. selling the topsoil or using it for construction fill. Besides demanding to know how dredging had worked in Decatur, the resolution even asked the Authority to look at particular piece of mobile hydraulic dredging equipment called the "Ellicott Mud Cat."

Supervisor Ken Boyd, however, found the measure "too extreme" and worried that it might sound like "a vote of no confidence" in Frederick. After some discussion, the resolution was tabled.

How safe is the dirt?

One of the frequently stated objections to dredging the Rivanna Reservoir is that hazardous materials may be lurking in the muck. However, the 2004 study did– at least partially– address that concern.

The study examined three samples from the Reservoir's bottom and found 25.3 mg/kg of lead in the sediment. If that sounds scary, it's actually lower, according to the EPA, than is typically found in nature, and it's far below the 500 mg/kg level that triggers warnings for playgrounds and households.

As for other so-called heavy metals– arsenic, silver, selenium, and mercury– each tested "below quantifiable measurements" in most or all Rivanna Reservoir samples. In other words, there just weren't enough of these toxic substances to register on the instruments.

The study suggests that pre-dredging prudence demands an additional test called a TCLP, or Toxic Characteristics Leaching Procedure. However, the dredging study– even though it cost the Authority tens of thousands of dollars– did not pursue such a test.

Richmond firm Air, Water, and Soil Laboratories Inc. reports that the cost for a 10-day turnaround of a full "T-clip," as engineers like to call it, is $875.50 per sample, or $1,313.25 for a five-day turnaround.

Minimum river supply

The Authority's official 50-year plan provides a new pipeline and a new Ragged Mountain Reservoir to vastly increase the area's current daily water supply. But what's received less fanfare are two components of the plan: the Rivanna Reservoir is being allowed to silt over, and Sugar Hollow and Rivanna Reservoirs will be forced to make mandatory daily releases into their rivers– even in times of drought.

Perhaps this partly explains why some environmental groups have been such enthusiastic supporters of the 50-year plan. Today's voluntarily releases from the Sugar Hollow Reservoir (into the Moormans River) and from the Rivanna Reservoir (into the Rivanna River) would become mandatory. Part of the job of the new Ragged Mountain Reservoir would be making up for those losses. But with data from two of the 2004 reports, the Hook found something surprising: dredging alone can fulfill all the area's water needs– even its needs in the year 2055, which is the justification for the $143-million plan.

Demand

This whole debate is based on the premise that the demand on the urban water system will double from today's average daily flow of 9.7 million gallons to the Authority's projected demand of 19.29 million gallons per day (MGD) in 2055, as stated in the the Authority's 2004 study, "Demand Analysis for the Urban Areas." But is demand really going to double? There are signs that the answer is no.

For starters, the population of the City of Charlottesville is projected to grow slowly– if at all– over the next 50 years. Second, while UVA– its hospital, its student body, and its footprint– have grown dramatically since 1983, aggressive conservation measures have resulted in no net increase in water use after 25 years.

That leaves Albemarle County, which has grown by about 1.014 percent annually over the past seven years. However, much of that growth has occurred in rural areas– where private wells are the norm– and in the designated growth area of Crozet, which has its own reservoir, Beaver Creek, whose supply is expected to last for the foreseeable future.

Critics of the Authority's new dam point out that today's average flow shows that conservation works. Indeed, before the drought of 2002, when installing low-flow toilets and meters on individual apartment units became the order of the day, the system's average flow was 20 percent higher, around 12 million gallons per day.

Planning

There's no law commanding a community to build a 50-year– or even a 25-year– supply instantly. Anyone wincing at memories of the 2002 drought, however– with the attendant plastic plates at restaurants, crispy lawns, and infrequent toilet flushing– may relish the idea of creating a new reservoir. But what about boosting the existing one?

A look at older studies suggests they were extremely optimistic or that today's studies are extremely pessimistic:

• a 1959 study estimated that the system then in place could produce 24.85 MGD in 1990;

• a 1985 study pegged the 1990 supply at 24.8 MGD;

• a 1994 study found the system could (thanks to the addition of a new pumping station on the North Fork) supply 27.2 MGD.

But such predictions nose-dived in 1997, the year a new study judged the system capable of supplying no more than 20.6 MGD. Still, that's more than we'll need in the year 2055: 19.29 MGD, remember?

The 2004 supply study comes from Gannett Fleming, and it's a bit bleaker. Yet even Gannett Fleming's 2004 "Safe Yield Study," prepared for the Authority, found that, despite siltation in the various reservoirs, the Authority's urban system today can offer a safe yield of 16 MGD.

Shifting calculations

It seems the Rivanna Reservoir loses about 15.1 million gallons of storage capacity per year to siltation, for a total loss of 634 million gallons of capacity since it opened in 1966. Yet that 2004 "Safe Yield Study" also found that for every 190 million gallons of added storage, the urban system gains 1 million gallons per day of daily water flow.

A quick math calculation (634/190) reveals that over the last 42 years we've lost 3.34 million gallons a day that could be reclaimed by dredging.

Therefore, adding the amount gained from completely dredging the Reservoir (3.34 MGD) to today's storage capacity (16 MGD) yields 19.33 MGD– more than the 19.29 MGD the Authority says we'll need in the year 2055.

For some reason, these data points have not been connected in the Authority's reports. And Supervisor Sally Thomas, before seeing the Hook calculations, said, "Removing all the silt from South Fork Rivanna Reservoir doesn't produce enough storage capacity for water to meet our community's 50-year needs."

Ironically, just two years after declaring that the water system can provide 16 million gallons per day, the Authority filed an environmental application with the state of Virginia alleging that today's safe yield is just 12.8 million gallons per day and claiming that dredging would not suffice to help us reach the 19.29 MGD demand in 2055.

Forget the Hook's calculations for a moment. On November 18, 2004, a Gannett Fleming manager told a public meeting held by the Authority board that dredging would supply 5.5 MGD.

"The numbers keep changing," says citizen blogger Blair Hawkins (super-blair.blogspot.com) wrote on January 3, 2008 the day after Frederick downgraded a recent drought warning to a drought watch.

"In 1977," Hawkins wrote, "the severity of the water shortage was measured in days of supply remaining. In 2002, the water shortage was measured in percent of total capacity. Because the 2007 drought was still milder, the new metric is level of reservoirs below full. But the height of the dam and area of the reservoir are never given, making it a meaningless metric. Today, the Daily Progress, WCHV, and WINA filled up space and air time with the meaningless measurements."

But Supervisor Thomas contends that the 16 MGD figure isn't right– that one must look at "safe yield," i.e. the amount of "useable water in the reservoir when water isn't running over the dam," she says.

"It's financially irresponsible to go forward without answers to the questions that come up," says Betty Mooney, a member of the citizens group. And she's not the only one trying to figure it all out.

While Albemarle supervisor Ken Boyd worried in 2004 about Sally Thomas's resolution and its hint of "no confidence" in Authority director Tom Frederick, last week Boyd told a reporter he has grown concerned about some of the revelations now emerging. Thomas, on the other hand, now describes herself as "excited" by the new Ragged Mountain reservoir. Like Frederick, she prefers to omit the cost of the 9.5-mile pipeline or the planned upgrade of the Observatory water treatment plant when comparing the options.

"The basic cost of expanding the Ragged Mountain dam is $37.5 million," says Thomas. "Your estimate is that dredging would cost upwards of $56 million. An expanded Ragged Mountain holds twice as much water as a constantly dredged [Rivanna Reservoir], meets our needs, and at the basic level costs $20 million less."

The Ellicott "Mud Cat"

Was Thomas on to something when she suggested three years ago that the Authority talk to the people who sell the "Mud Cat"? Steve Miller thinks so.

The regional manager of Ellicott Dredges LLC, Miller has been in charge of selling Mud Cats for five years. In all that time, he says, he's never been contacted by anyone from Charlottesville.

"If they'd like to call me in," he says, "I'd be happy to do that. We're the industry's leading provider of dredging equipment– we did $100 million in business last year."

"The devil is in the details," says Albemarle Supervisor Dennis Rooker, claiming that finding a field big enough for "dewatering" the dredged material would be difficult. However, Miller says the land doesn't have to be on or even near the banks of the reservoir. He says he assisted a dredging job in Florida that pumped the sediment 17 miles.

"I don't care if you want to pump to China," says Miller. "It's just pipes and pumps."

At a 2004 Authority meeting, a Gannett Fleming official named Aaron Keno showed nightmarish slides of how dredging would ravage the peace of the reservoir, calling it an every-year-for-50-years process that would fill the Reservoir area with smoke-belching equipment and a daily stream of trucks hauling away the spoils.

That's when John Martin stood up to ask if Gannett Fleming had actually talked to any other American communities such as Decatur, Illinois, to see how dredging worked for them.

Keno admitted they had not.

Had Keno investigated, he might have learned about what went on in Decatur. There, officials wanted to remove sediment that had been accumulating in their drinking water reservoir for 50 years. The operation, which took place in 1992 and 1993, removed over 2 million cubic yards, about 40 percent of the anticipated size of a Rivanna dredging project.

The sediment was pumped via 18" plastic pipe through a pristine wooded area, across two ditches and two county roads. Because Lake Decatur is surrounded by homes, the project employed "hospital-quiet" pump motors– and an Ellicott Mud Cat.

Total cost including disposal: $6.85 million.

Back in Albemarle

Charlottesville developer Oliver Kuttner remembers 1991 when his Free Bridge-area foreign auto dealership, despite having a working well that he says never went dry, was pushed to connect to the urban water system.

"Part of why you run out of water," Kuttner says, "is that you run around trying to connect people who don't want to be connected."

As previously reported in the Hook, some dredging contractors believe that the Gannett Fleming estimate, the one that topped out at $145 million, was too high– by a factor of three or four. Kuttner says he'd do the job for $30 million.

"It would be a dream job," he says. "I'll buy a Mud Cat; I'll make so much money."

Earlier this week, Frederick, responding to a Freedom of Information request from the Hook, supplied a Gannett Fleming memo that now claims that dredging the Rivanna Reservoir would cost not $145 million, but a possible $225 million.

Frederick first mentioned this updated estimate publicly in November 2007 before City Council, when– facing dropped jaws and stunned skepticism– he promised to promptly post the new report on the Authority website.

Three and a half months went by. On March 4, despite a drumbeat of disbelief over the immense figure, Frederick insisted that the updated report existed– he just couldn't find it.

Finally, on March 11, Frederick produced the memo. It's dated March 3, 2008.

Meanwhile, for a community wondering where to get water in times of drought, additional shockers are tucked into Gannett Fleming's 2004 "Safe Yield Study."

It turns out that the consultants knew that both 35-acre Lake Albemarle and 104-acre Beaver Creek Reservoir lie above a deactivated 2-million-gallon-per-day drinking water pumping station on the Mechums River. Moreover, the report suggests that 60-acre Chris Green Lake, like Lake Albemarle and Beaver Creek, could serve as a "last resort" by releasing water in times of extreme drought.

Instead of considering these calculations and possibilities, however, the Rivanna Authority appears to be proceeding full-speed-ahead with plans for the new dam. And Gannett Fleming– whose grim depictions of dredging the Rivanna appear to have steered this community away from saving our key reservoir and whose studies omit any analysis of several existing waterways– has earned over $2 million for the studies it carried out for the Rivanna Authority from 2002 to 2007.

Last October, the firm won the $3.1 million contract for engineering the new Ragged Mountain dam, and a new torrent of money began to flow. In all, 15 Gannett Fleming engineers are billing at over $100 an hour, and– according to the contract's fee schedule– Keno is one of three Gannett Fleming officials whose time is billed to local water users at $205 an hour. The administrative assistant's time is billed at $79, and three of the firm's clerks are considered so valuable that their time is billed at $69 per hour. A Gannett Fleming spokesperson declined comment.

Back in Illinois, Nick Burton, a former Decatur City Council member, called his city's dredging "a forward-looking project that shows a commitment to the preservation of this lake so it will not someday fill in and become a mud flat," as quoted in an industry newsletter.

"Because of its huge magnitude and cost benefits," he said, "this very critical water supply lake-dredging project will be closely watched by many governmental agencies."

Alas, not all governmental agencies have been watching.

#

Correction: March 13, 2008

* This story misattributed the affiliation of Jeff Werner, who actually works at the Piedmont Environmental Council, not at the Southern Environmental Law Center.

Previous stories on this topic:

• COVER- Reservoir dogged: A $142 million boondoggle?

• NEWS- Higher and higher: Frederick claimed dredge cost $225 million

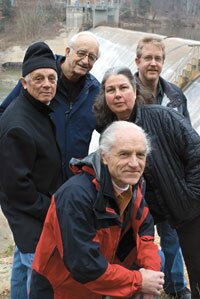

Members of Citizens for a Sustainable Water Supply have questioned the numbers and the studies emerging from the Authority.

FILE PHOTO BY JAY KULHMAN

Authority director Tom Frederick contends that the cost of dredging should be measured only against the cost of the new $37.2 million Ragged Mountain Reservoir.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Three years ago, the Albemarle Supes almost asked the Rivanna Authority to consider a Mud Cat. Almost.

COURTESY ELLICOTT DREDGES

"I'll buy a Mud Cat; I'll make lots of money," says contractor Oliver Kuttner, who adds he would dredge for $30 million.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

In 1980, Albemarle Supervisors downzoned much of the land around the Rivanna Reservoir to preserve the watershed and then defended the decision all the way to the state supreme court. Today, however, the reservoir as a water storage body is doomed by the refusal to dredge.

FILE PHOTO BY JAY KULHMAN

Although bolstered by raising the crest of the dam in the late 1990s, the three million gallons-per-day Sugar Hollow Reservoir will be removed from service under the 50-year plan.

PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

Allowing the Moormans River to run free, as seen here last Sunday, March 9, from Sugar Hollow Road, is a goal of the 50-year plan that gives Charlottesville one giant reservoir instead of the three it has today.

PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

#