ESSAY- Roger and we: Mr. Ebert returns to Charlottesville (sort of)

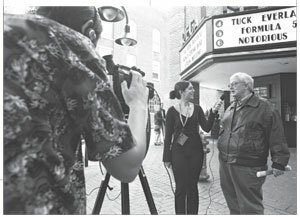

Ebert meets the press outside the Regal cinema in 2002

COURTESY VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

It was October 1992 when I got the call. It was an administrator with the Virginia Film Festival, which was scheduled to start its annual run just a few days later. Earlier that year, I had purchased a struggling downtown movie theater, and I was being asked to make a donation of sorts.

"We need a venue for four consecutive mornings, and we're not offering any money because we've already spent our budget. But this a new event, and it sounds like a lot of fun."

Hmmm.

"I guess we could find a spot at UVA," said the administrator, "but wouldn't it be cool to have Roger Ebert at your theater?"

Indeed it would. And so it was that the Jefferson Theater (now under new ownership as a hip concert venue) helped launch a Charlottesville cinematic tradition.

For four days, we sat in the dark and learned about the greatness of Citizen Kane–- and of Roger Ebert. It was democracy, or "democracy in the dark," as Ebert called it. Anyone could yell 'stop' to interrupt with a question.

And interrupt they did. "Isn't that," asked one woman, "a rather intrusive camera angle?"

Ebert explained how the great Orson Welles accomplished such intrusion–- in a scene that peers in on Kane's talentless mistress–- via use of a breakaway neon sign that indeed allowed the camera to defy physics to find the lover through a skylight.

Meanwhile, Ebert and the love of his life, his wife Chaz, went about enjoying their extended Charlottesville weekend, as the then newlyweds strolled the Downtown Mall, lunched at the Coffee Exchange, and generally avoided getting bothered– even though Siskel & Ebert at the Movies was then one of television's most popular syndicated shows.

Likewise, Ebert's workshop was a hit. With little advertising, eager attendees filled the Jefferson's 184 stadium-style seats for four straight days of Kane.

"Few people can pull that off– with the charm, the talent, and the expertise– and Roger has all those," recalls then Festival director Bob Gazzale. "One of the great things about Roger is that he appreciates what this Festival is about, an academic approach to film, apart from stars; and his workshop embodies that."

The Chicago-based critic returned the following fall to do the same thing to Sunset Boulevard and again at the subsequent Festival in 1994, when he workshopped Hitchcock's Vertigo (and spoke of his own foray into screenwriting with the naughty cult classic, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls).

The next spring, Ebert was back in Charlottesville, this time as a "Kluge Fellow," and he reprised the workshop idea with what he recognized as an instant classic, Pulp Fiction, in UVA Law's Caplin Auditorium. There, Ebert explained to us, his eager students, the cinematic concept of a "mcguffin," something that drives a plot forward. When my seatmate called a briefcase's golden glow an "egg mcguffin," I shushed him. Moments later, someone else re-coined the bon mot, and the place erupted in laughter. Shows how little I know.

Unfortunately, Ebert himself would eventually be shushed by disease. But not before going in-depth in Charlottesville on The Third Man, Bonnie & Clyde, Blowup, and The Birds.

Carroll Trainum, the Festival volunteer who manned the video-disc player for many of those workshops in the pre-DVD era, recalls how taken-aback Charlottesvillians were when he insisted that the strangers shouting "stop" call him by his first name.

"Roger set the standard for film-watching seminars at our Film Festival that may never be met again," says Trainum.

The last year Ebert headlined Charlottesville was 2002 when he came to workshop Chinatown, the movie about a nefarious plot to divert water, amid a Festival whose theme was "Wet" and amid the waning days of a big regional drought.

"Water," he explained, "will be the most precious commodity of the 21st Century, not oil, which can be replaced by other power sources."

He was right about that, as water continues to roil Charlottesville policymakers. But sadly, the great critic can no longer offer such analysis verbally, having lost his voice to complications from cancer of the thyroid and salivary glands. The bottom of his distinctively square jaw has been removed, forcing his face into a sort of permanent smile. He can't eat solid food, and he has trouble sitting upright.

Many people who knew Ebert only from television may be under the impression that his work is over. Hardly. He remains one of America's most prolific critics. He's a Pulitzer Prize-winner, and despite the physical travails, he continues to review at least four films every week– when he's not busy with his blog or one of his books, of which he has penned at least a dozen.

Recently, in a poignant feature in Esquire, the reporter concluded that Ebert is "dying in increments." ( "Well, we're all dying in increments," he responds on his blog.)

During a year-ago interview with Leonard Maltin, Ebert– poised at his laptop computer– expressed gratitude that he can still communicate.

"I still have the written word," he says in a synthesized voice. "That has been my first love, and I still continue at full speed."

Recently, I discovered that I could be running his reviews in the Hook. Given his talent and his long and friendly connection to Charlottesville, that was a pretty easy decision. Full speed ahead.

~

Hook editor Hawes Spencer regrets that he attended just two of Ebert's scene-by-scene workshops.

#