Midnight rider: How Jack Jouett saved Virginia

-

Jack Jouett played by independent historian Gary Lettan with "Sally" played by Cameron Creek, owned by Roxanne Booth.photo by Tom Daly

Jack Jouett played by independent historian Gary Lettan with "Sally" played by Cameron Creek, owned by Roxanne Booth.photo by Tom Daly -

If you can read this text, then you don't have to read this long story-- or feel its drama.photo by Tom Daly

If you can read this text, then you don't have to read this long story-- or feel its drama.photo by Tom Daly -

Tarleton was called "Bloody Ban" after the massacre in South Carolina.detail, painting by Joshua Reynolds

Tarleton was called "Bloody Ban" after the massacre in South Carolina.detail, painting by Joshua Reynolds -

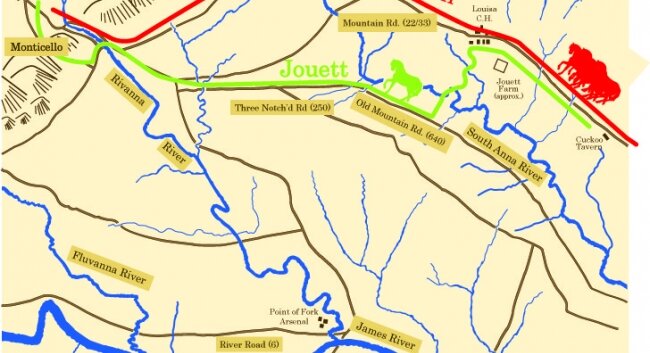

The Ride, June 3-4, 1781

The Ride, June 3-4, 1781 -

Jouett knew of an old logging/farm trail that connected Mountain Road to Old Mountain Road and then on to Three Notched.photo by Tom Daly

Jouett knew of an old logging/farm trail that connected Mountain Road to Old Mountain Road and then on to Three Notched.photo by Tom Daly -

After sending his family ahead, Jefferson tarried before heading up the ridge to Carter's Mountain.photo by Hawes Spencer

-

It's a good thing he knew the detour.photo by Tom Daly

It's a good thing he knew the detour.photo by Tom Daly -

Jack JouettDaughters of the American Revolution

Jack JouettDaughters of the American Revolution

It was the evening of June 3, 1781– a Sunday– and war was on its way to Charlottesville.

Nearly forty miles to the east, at Cuckoo Tavern, John Jouett Jr. had finished dinner and gone outside to catch a few winks. Because of the oppressive late spring heat and the food and drink sitting heavily in his gut, “Jack,” as his friends called him, was soon fast asleep despite the revelry droning on in the background. Jouett was curled up under a great elm near the tavern’s picket fence, the only thing separating him from the county road.

A couple of hours before midnight, he was startled awake. Although Jouett was a strapping figure and an excellent horseman, the sight he saw as he peered into the moonlight toward the steadily approaching clatter had to be absolutely terrifying: a 250-man raiding party filling the dusty roadway for about 200 yards. At the head trotted the green-jacketed horsemen whose very name had grown infamous: the British Legion.

They were dragoons– horsemen armed and drilled to also fight dismounted— who were crown loyalists from New Jersey, Philadelphia, and New York City. A year earlier at the Battle of Waxhaws in South Carolina, these same cavalrymen– hardened Americans who had sworn allegiance to King George– had hacked their way through Virginia Continentals attempting to surrender. With sabers slashing, the Legion massacred dozens of patriots. Jouett would have heard the stories.

A ruthless leader

Bobbing alongside the vanguard that night was the Legion’s leader, Lieutenant Colonol Banastre Tarleton, a 26-year-old Liverpudlian who had risen in the ranks thanks to his fast riding, hard fighting, and ruthlessly aggressive nature. To the British, wrote historian Winthrop Sargent, Tarleton was “a capital horseman, the very model of a partisan leader.” To the Americans, however, he was the “Green Dragoon” or “Bloody Ban,” the commander– and, as it turned out, the butcher– at the massacre at Waxhaws.

“Tarleton’s Quarter!” had become a patriot rallying cry; it meant death to enemy troops with their hands in the air.

The road through Cuckoo (then, as now, just a tiny village in Louisa County), ran northwesterly to Louisa Court House, then onward to the gap in the Southwest Mountains at Pantops, a distance of about 38 miles. Just beyond sat the previously unimportant town of Charlottesville.

About three weeks earlier, however, the patriots had lost Richmond, so Charlottesville became the temporary state capital with the entire government— both houses of the legislature and Governor Thomas Jefferson– ensconced in Jefferson's hometown in the foothills. Jouett's father, John Jouett Sr., was the proprietor of Charlottesville’s Swan Tavern, just across from the courthouse, and at that very moment, no doubt, a number of the unsuspecting assemblymen were sampling the fare at Swan Tavern.

Inflamed by the sight of the enemy passing by him at Cuckoo Tavern, Jack Jouett’s thoughts must have raced. He would have instantly surmised Tarleton’s destination. But could he beat them to Charlottesville to sound the alarm? How could he get around them? Was his horse up to the challenge of such a long and treacherous ride?

Understanding the dire circumstances, Jouett quickly determined to risk his life in an attempt to thwart one of his country’s most fear and despised, enemy commanders.

Unlike the legendary “Midnight Ride” of Paul Revere— much celebrated in poetry, paintings, and even U.S. postage stamps— Jack Jouett’s overnight race from Cuckoo to Charlottesville remains relatively obscure. Perhaps it’s because Jouett, unlike Revere, was not already wealthy or famous when he undertook his heroic feat. And perhaps it’s because Jouett sought his post-war fortune out on the frontier, away from the centers of population and publicity.

Whatever the reason, the Central Virginian’s desperate dash, under the light of scrutiny, far outshines the Bostonian’s. Revere rode 15 miles on well-traveled Massachusetts roads, while Jouett rode at least 40 through the Virginia frontier. Moreover, the stakes in Virginia were higher. The state’s civil leadership, in its entirety, was seemingly Tarleton’s for the taking.

The war comes to Virginia

In 1781, the American Revolution was in its seventh spring, and things were not going well. Remarkably, the Old Dominion, supposedly the country’s most populous– and arguably its most powerful– state, had buckled quickly under the enemy’s blows with the entire administration skeddadling like a flock of frightened geese. How had the situation gotten so grim?

The tide had begun turning on December 30, 1780 when traitor Benedict Arnold— now an enemy general— had sailed up the James River with 1,800 men aboard 27 British warships. With the new capital at Richmond, with its military supplies and tobacco-packed warehouses, the obvious target, the last six months of Jefferson’s second one-year gubernatorial term were about to get ugly.

“When the general panic set in,” wrote historian John E. Selby, “the governor fled from the city with his family in the early morning hours of January 5.” Arnold captured the city that afternoon.

Two weeks later, after much burning and looting at Richmond and elsewhere along the James, Arnold sailed downstream to Portsmouth to dig in. Meanwhile, all across Virginia, county lieutenants desperately attempted to muster their militiamen, but too few turned out.

In April, a British fleet landed over 2,000 reinforcements at Portsmouth, and over the course of that month, the British launched several raids and actions fought all along the James— including a one-sided naval contest located between Richmond and Petersburg at a place called Osborne’s Landing. There, on April 27, the entire Virginia navy was lost, including—perhaps prophetically— a warship called Jefferson.

When the British again advanced against Richmond on the last day of April, this time they encountered French-born Major General Marquis de Lafayette at the head of 900 northern Continentals dispatched from George Washington’s army. The capital was rescued at the eleventh hour.

For the next month, this Lafayette-led force— augmented by some 1,500 untested militiamen— was the largest the Old Dominion could muster, but soon the 24-year-old Frenchman was greatly outnumbered.

The new British leader, General Charles Lord Cornwallis, had marched into Virginia from North Carolina with 1,500 additional British soldiers, and another 1,500 arrived by sea. Cornwallis was an experienced and aggressive officer with a consolidated British field army of about 7,200 veterans.

After remaining relatively unscathed for the war's first six years, Virginia had become the war’s most active theater.

"To frustrate these intentions"

“Cornwallis was not an aristocratic dilettante,” says Andrew O’Shaughnessy, director of the International Center for Jefferson Studies. “He was a real military professional. He was also a gambler, someone willing to take major risks. He essentially wanted to make Virginia collapse.”

Frustrated at his inability to ensnare Lafayette— whom Cornwallis called the “aspiring boy”— the 43-year-old Britisher decided instead to raid Virginia’s interior. Knowing that the governor and the relocated legislature would soon call out more state troops, Cornwallis ordered Tarleton— the brutal cavalryman— “to frustrate these intentions, and to distress the Americans, by breaking up the assembly.”

It was May 10, 1781 when the Virginia legislature determined to quit the state capital and reconvene in Charlottesville, beyond the Southwest Mountains.

Early on June 3, Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton set out from Hanover Court House, north of Richmond, with 180 dragoons from his own Legion and 70 mounted infantrymen from the 23rd Regiment, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. These improvised horsemen, foot soldiers atop horseflesh stolen from the Virginia countryside, rode with light muskets slung across their red tunics.

At the time, an average horseman traveling unchallenging terrain could expect to cover 30 miles in a day. Tarleton had something much bolder in mind. As he later wrote, he planned “a march of seventy miles in twenty-four hours.”

Because the weather was unusually hot, however, the going was slow, and Tarleton’s column spent most of the first day to reach Cuckoo Tavern, a distance of about 30 miles. In order to bag his game, however, Tarleton was pushing his men to cover more.

It was about two hours before midnight when Jouett awakened to see the enemy raiders trotting past Cuckoo Tavern.

Jouett quickly donned his riding boots, “scarlet coat, and military hat and plume,” wrote Jefferson biographer Henry S. Randall. His bay mare Sally— which another historian called “the fleetest steed in seven counties," was nearby in the tavern’s paddock.

It would have been much easier to go back to sleep and hope that someone else could save Virginia’s government. Jouett knew, however, that his knowledge of the wilderness trails was unsurpassed. Providence could not have selected a better messenger.

A history in taverns

Born in Albemarle County on December 7, 1754, the 26-year-old Jouett has been widely described as intelligent and resourceful. He was also a strapping young fellow, according to Joel Meador, executive director of the Jack Jouett House in Versailles, Kentucky.

“He stood 6 feet 4 inches tall, and weighed about 220 pounds.” Unfortunately, little is known of his early days. “He was the son of a tavern owner,” says Meador.

Indeed, the running of wayside taverns— a lucrative business in the days when friendly stopping-places were few— seems to have been in the Jouett family blood. In 1742, Jack’s grandfather, Matthew Jouett, had opened an “ordinary” in his house near the present-day town of Louisa. Matthew’s son—John Jouett Sr., Jack’s father— had once been the owner of Cuckoo Tavern itself. After selling that establishment in 1773, Jouett Senior, wrote Edgar Woods (Albemarle’s first historian), purchased “one hundred acres adjoining [Charlottesville] on the east and north, and at that time most likely erected the Swan Tavern, of famous memory.” During the Revolution Jack Senior acted as a commissary, wrote historian Virginius Dabney, selling “considerable beef and other needed supplies... to the quartermasters of the Continental Army.”

The standard story— that Jack, as wrote Dabney, “was a captain in the Virginia militia, as were his three brothers” does not hold up under examination. A search of the state’s militia records revealed no Captain John Jouett. Instead, one of the early accounts—Randall’s 1858 biography of Jefferson—referred to Jack as a “showy gentleman” who “was no officer,” but had “an eccentric custom” of wearing military-style getup.

Patriotism, evidently, was also a dominant trait in this French Huguenot family. With two Jouetts serving in the Virginia Continental Line (the regular army at the time)—older brother Matthew in the 7th Virginia (mortally wounded at the 1777 Battle of Brandywine), and Robert in Col. James Wood’s 12th Virginia– Jack and his father may have felt compelled to make a political statement of their own. In June of 1779 both signed the curious Albemarle “Declaration of Independence” which stated in part that: “we renounce… all Allegiance to George the third… [and] will be faithfull & bear True Allegiance to… Virginia as a free & independent state.”

An abandoned road

Freedom and independence were certainly at stake as Jouett began sorting his thoughts on that moonlit night. Jouett had no way of knowing if anyone else was was to get ahead of Tarleton’s troopers. If he was indeed acting alone, the Old Dominion’s fate was resting on his skills, the evening’s visibility, and Sally's speed.

Cantering along Mountain Road, the main highway, at a safe distance behind Tarleton’s column, Jouett must have realized he had to get around them to beat them to Monticello and Charlottesville. Finding a detour might be an impossible proposition on a dark night. Fortunately, this one had a nearly full moon.

Moving cautiously once he neared Louisa Courthouse, Jouett must have caught a glimpse of polished buttons and metal-sheathed sabers, as historian Tapp wrote, that in the moonlight he "could see dimly the dragoons moving about.” The raiders had stopped to water their horses and refresh themselves, and Tarleton later wrote that he “halted at eleven near Louisa court house, and remained on a plentiful plantation till two o’clock.”

In the dense wilderness that covered Virginia in the 18th century, well-maintained roads were in short supply. While Mountain Road was blocked by the Loyalist forces, Jouett knew that to its south, across the South Anna River, was Three Notch’d Road leading all the way from Richmond (where it's called Three Chopt Road) to the Shenandoah. To best outstrip Tarleton, therefore, Jouett had to find a way southwestward, toward the road whose famous signposts— trees bearing three hatchet chops, like chevrons— would thereafter guide him to Charlottesville.

But how? Somewhere nearby was the answer: an old logging trail that had supplied the logs for the court house.

"He knew the trail well," wrote historian Tapp, "having hunted along it.”

So off he and Sally went.

“His progress was greatly impeded by matted undergrowth, tangled brush, overhanging vines and gullies,” wrote Virginius Dabney. “[H]is face was cruelly lashed by tree limbs as he rode forward, and scars said to have remained the rest of his life were the result of lacerations sustained from these low hanging branches."

Drenched with sweat, Jouett splashed through the South Anna somewhere south of Louisa Court House. Perhaps he stopped briefly to water Sally, and perhaps he even washed off her flanks, now covered with scratches. Soon he was back in the saddle.

“He could judge by the position of the moon that the night was far spent, causing him to travel faster,” wrote Tapp, “He was determined to beat Tarleton or die in the effort.”

Within a few miles, Jouett turned on to Old Mountain Road and then onto Three Notch’d. Heading west along the latter well-marked byway, Jouett spurred Sally to even greater efforts. He still had miles to go, and Tarleton’s force was still on the move.

The Affair of Carter's Mountain

Before daybreak, the marauders had detained “some of the principal gentlemen of Virginia” and captured a member of the Continental Congress, Frances Kinloch, and burned 12 wagons carrying weapons and clothing for the Continental Army.

At Castle Hill, the Keswick-area estate of Dr. Thomas Walker— discoverer of the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky— the British cavalrymen rested for half an hour. This brief stopover has been the subject of numerous tall tales, all involving an elaborate, delaying breakfast. None, however, should be believed, because Tarleton would not have fallen for such a ruse. He was in a hurry.

Meanwhile, Jouett and Sally were crossing the Rivanna River at the village of Milton and then ascending Monticello Mountain three weary miles later. It was 4:30am.

How Jouett must have appeared upon arrival is lost to history. What is recorded is that Jefferson's guests included members of the General Assembly including the speakers of both houses. Jefferson would later write that the legislators “breakfasted at leisure” before proceeding to Charlottesville.

Legend has it that as Jouett remounted to spread the alarm Jefferson offered up a glass of fortifying Madeira.

Jefferson himself, however, remained unhurried. Perhaps it was because his ill-fated governorship had ended two days earlier. (This meant, of course, that at the moment Virginia had no chief executive.)

After sending off his family and carefully organizing his papers, Jefferson was warned again of the British approach, as he could see– via telescope– soldiers arriving in Charlottesville. Finally, he galloped up the adjoining wooded slope where he'd sent his family. Ascending nearby Carter's Mountain, Jefferson was mere minutes ahead of the first loyalist dragoons under a detachment led by Captain Kenneth McLeod.

Two of Jefferson’s slaves, Martin and Caesar, "were engaged in secreting plate and other valuables under the [planked] floor of the front portico, when McLeod’s party arrived," according to Randall. Just as the last piece of silver was handed down to Caesar “in the cavity,” Martin either heard the hoofbeats, or saw the loyalists through the trees, “and down went the plank, shutting Caesar into the dark hole below.” There Caesar would remain “without light or food” until McLeod’s troopers departed, many hours later.

Although Jefferson quickly rejoined his family at the nearby estate of Blenheim, he later referred to this extremely troubling episode— the so-called “Affair of Carter’s Mountain”— as the nadir of his political career.

Daniel Boone and Jouett

Little Charlottesville, in the meantime, was a blur of activity. Warned by Jouett, the assemblymen hastily convened and decided to meet again three days later in Staunton, forty miles further west. Then they scattered.

After dispatching McLeod to Monticello, Tarleton had charged through Moore's Creek and overpowered a small militia force at Secretary’s Ford, eventually site of the Woolen Mills, and then thundered onto the courthouse square. Most of the flock, of course, had flown.

“Seven members of the assembly were secured,” wrote Tarleton, neglecting to list their names, “and several officers and men were killed, wounded, or taken.” During their one-day stay, the British discovered “a great quantity of stores,” and destroyed “one thousand firelocks... [u]pwards of four hundred barrels of powder” and “[s]everal hogsheads of tobacco.”

Jack Jouett’s later activities that morning are difficult to sort out.

Historian Randall wrote that Brigadier General Edward Stevens— wounded in battle and now serving in the legislature— was able to elude the British dragoons because he was dressed as a Virginia farmer and mounted on a shabby horse. “Mr. Jouett,” however, thanks to his ersatz military attire, “was more attractive game.” So the enemy took off after him instead. “After [Jouett] had coquetted with his pursuers long enough, he gave his fleet horse the spur, and speedily he was out of sight.”

Another story revolves around Daniel Boone. Representing the massive western Virginia county of Kentucky, the famous frontiersman was among the legislators in Charlottesville that day. As noted in My Father, Daniel Boone, youngest son Nathan Boone related the following 70 years later:

“[W]hen Jack Jouett gave notice of Tarleton’s approach, my Father… remained, loading up on wagons the public records. [W]hen they were overtaken by the British, questioned hastily, and dismissed… [Jouett] called out, ‘Wait a minute, Captain Boone, and I’ll go with you.’” An enemy officer then asked, “Ah, is he a captain?” and took Boone into custody. Conveyed to the British camp east of town, and held overnight in a coal house, the legendary frontiersman was reportedly interrogated by Tarleton and released.

The two stories are difficult to square, as they seem contradictory. One has Jouett racing away from Charlottesville because of his ostentatious military garb. The other has him completely overlooked by the British— despite shooting off his mouth at the courthouse. Did either of these events take place? We’ll probably never know.

What we do know is that on June 15, 1781, just two weeks later, the assemblymen resolved that Jouett should receive “an elegant sword and pair of pistols as a memorial of the high sense which the General Assembly entertain of his activity and enterprise.”

After all, thanks to Jouett’s ride, four signers of the Declaration of Independence escaped capture: Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson Jr. and Richard Henry Lee. A “Who’s Who” of Virginia history, this extraordinary list comprises a future president (Jefferson), the father of another future president (Harrison, whose son William Henry was elected in 1840), and the man who next became Virginia’s governor (Nelson). Patrick Henry was also among the escapees, as was the father of John Tyler, Jr., who followed William Henry Harrison into the White House.

Epilogue

Jack Jouett got the pistols two years later, but his receipt of the sword was delayed twenty years. By that time, he’d made quite a name for himself out on the frontier.

Jouett had managed Swan Tavern for a spell, but in 1781, like thousands of other Virginians, he lit out for Kentucky. Two years later, he married Sallie Robards, a relative of Andrew Jackson’s, and the couple had 12 children. In 1787, and again in 1790, according to historian Lewis Collins, Jouett represented his region of Kentucky in the Virginia General Assembly. The year Kentucky gained statehood, 1792, Jouett was elected to the new state legislature. Jouett was an agricultural leader as well; he imported livestock in large numbers and thus helped the Bluegrass State achieve its cattle- and horse-breeding fame.

In Kentucky, Jack Jouett is remembered as a high liver, a man full of humor and fun. Remarkable for his hospitality, Jouett, became a friend of Henry Clay and Andrew Jackson, "indeed of all the great men of early Kentucky," Collins wrote.

Jack Jouett died at Peeled Oak, his Bath County, Kentucky farm, on February 21, 1822. He was buried in the nearby family cemetery, where unfortunately, says Meador of the Jack Jouett House, "all the stones have been lost." Somehow it seems fitting that the Central Virginia patriot whose early life and heroic deed have been mostly lost to history, now lies lost out on the Kentucky frontier.

“Even in death,” says Meador, “he’s still very much a mystery.”

~

Rick Britton writes about history and makes maps for many publications, including books he has written. His other Hook cover story was "Unhappy Grandpa," a 2008 piece about the twilight years of Thomas Jefferson.

24 comments

There needs to be a revision to the Hook's link to this article from the front page. It says "Jouett beats Revere any day and night."

Whatever Virginians want to tell themselves about Jack Jouett's ride, it did NOT result in a bunch of Minutemen shooting up the redcoats in the very first skirmish of the Revolutionary War. The British were chased out of Boston by March of 1776. The "civil leadership of Virginia", or whatever it is that Jouett is supposed to have saved, is not NEARLY as important to the eventual outcome of the Revolution as the defeatS the British suffered "up North".

A bunch of rich Virginians being alerted to the fact that they'll soon have to surrender Charlottesville (which, oddly, never happened in Boston after Revere's ride), may be a nice story if you're a well-off, white Virginian. Pardon the rest of us for not caring a whit.

Jouett deserves praise, but the Hook makes itself look like another provincial, backwater rag by trying to take down a True American Hero and making this local hero into something he clearly is not.

The ride of Paul Revere was at a time and context far, far different from Jack Jouett's ride. To not recognize this, you'd have to be an absolute dullard.

Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, Boston, Trenton, Saratoga.... by the time the war entered Virginia, the Yankees and French had already beaten the British, and it was only a matter of time before this fact resulted in a British surrender.

Jack Jouett's ride may have allowed Thomas Jefferson to run away like a coward over Carter's Mountain, but it didn't accomplish much more than that. Wheras the Northern version of heroism resulted in one of the most famously heroic skirmishes in world history, this local ride resulted in not much more than a rich guy running away and leaving his slaves and his own children behind.

It is so typically Charlottesville to try to turn this into something greater than it is.....

Write about Jouett on his own terms. Please don't compare and try and take down the legacy of Paul Revere. The title of this article is just silly. The conclusions seem to be already drawn before the article was written? I would research Revere and his ride a little more before casting him the way you do in this article.

Both Revere and Jouett are important for the roles they played. Someone once pointed out that Jouett was lesser known because he didnt't have a Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to immortalize him in a poem.

I have wondered what if Tarleton had been successful and captured Jefferson and perhaps executed him. It would have changed the course of history in many ways. Would there have been a Louisiana Purchase? Would there have been a university established in Charlottesville.

While he may have been held hostage or perhaps sent back to England for trial, the capture of the author of the Declaration of Independence would surely have been a harsh blow to the colonials' morale.

Maybe Harry Turtledove will write a novel with this theme in one of his alternate histories.

@meanwhile: Wow, sectionalism seems to be alive and well in the 21st century. . . . The fact of the matter is that, despite all the great northern victories listed, the war in early 1781 WAS NOT a foregone conclusion: British Lieut. Gen. Sir Henry Clinton was still heavily fortified at New York City, the powerful British Navy still commanded the Atlantic seacoast (and the Chesapeake Bay), and (a bit later) British Lieut. Gen. Charles Lord Cornwallis was overrunning the State of Virginia (the most populous of the original 13). George Washington at the time was still trying to figure out how to assault Clinton and retake New York. Meanwhile, French Lieut. Gen. Jean Baptiste, Comte de Rochambeau (who led the French expeditionary force) was trying to talk Washington out of it. But don't believe me, look it up. And while, as you say, Revere's ride led to a "skirmish," the skirmish that sparked the war, no doubt, but a "skirmish" nonetheless, Jouett's ride probably Virginia's government from capture, and eventually led—fewer than 5 months later—to Yorktown, the major American victory in Virginia that virtually ended the Revolution.

Also: Far from "casting aside" Revere's herioc ride—I titled my piece "From Cuckoo to Charlottesville"—what I'm saying is that Revere had a major poet to dramatically set down, and exaggerate, his feat. Jouett's heroic ride has been overlooked and needs to be re-examined considering the situation at the time—excluding modern perception, that's called "presentism." Do I believe that Jouett's ride was ultimately more important than Paul Revere's? Yes, I do.

If Jacks ride saved Thomas Jefferson from execution than that fact alone is worth the price of admission.

"Rah, rah, rah. Go Paul Revere!" That's all I've been hearing for more than 230 years. Whatever happened to me???

"Do I believe that Jouett's ride was ultimately more important than Paul Revere's? Yes, I do."

Well, you would be wrong. The Declaration of Independence never would have been proposed by John Adams had the Massachusetts colonists not taken up arms against the British. It was the blood spilled that compelled the Continental Congress to consider breaking away from England more than any dispute over taxation, and the minutes of the Continental Congress bear this out.

To say, 5 years after the fact, that the Declaration of Independence's primary author's life or liberty was more important to the cause of independence than the ACTUAL REBELLION is exactly the sort of provincial, sycophantic historical revisionism that drives true students of history batty.

Yes, Jefferson's capture MAY have resulted in a lowered morale for the Continental Army. Or he may have become a martyr to the cause.

You are welcome to your opinion, but that does not mean that your opinion is correct. It simply is not.

@meanwhile: Any legitimate point you're trying to make is rendered invalid by the tone of your diatribe. "Rich Virginians," "typically Charlottesville," "provincial, sycophantic," etc. etc. Any "TRUE student of history" would not find it necessary to belittle an entire region in such a manner. Your comments prove you to be more spiteful and ignorant than those you are attacking.

@Rick Britton: I thoroughly enjoyed reading this article. It is fascinating, well-written, and obviously extremely well-researched. Thank you!

@meanwhile: "Well, you would be wrong."

You don't think that the colonists would have fought at a future date if the Regulars had got to Concord unannounced? And why credit Revere? He never made it to Concord like I did.

At least Jouett's story is accurate.

Great article--having missed a 7th grade Virginia history class, I really didn't know much about our boy Jack. Thanks, Rick, for your lively writing and teaching some of us a thing or two.

And @meanwhile, your snarkiness is out of line, you can disagree without being insulting. Fact is, both were important moments in history, but Paul's ride definitely got hyped/magnified in the public mind. And the others involved in the event, like Samuel Prescott, have been forgotten. Maybe you'd like to try to write an article about him and tell us why he's a forgotten hero...or maybe you just want to snipe at a real writer?

An excellent piece. Thank you. No need to trivialize it by comparing to Revere. Give us more of this stuff!

this paper has really gone down hill. Does anyone there do any real reporting or work. The articles are trivial or just incorrect & the entire paper is an eyesore. Really LAME!

Thanks for the article! As a "provincial" Louisan, I'm thrilled to see Jack get his props. Many in these parts have long held that if VA had a poet the likes of Longfellow, Jack might be known far & wide too! :) In any case, it's an engaging piece of local history. Also, for what it's worth, I think The Hook is Cental Virginia's best newspaper! Thanks for the insightful, provocative journalism.

Rick Britton joined us today on "Charlottesville—Right Now!" to discuss the article. Podcast is here: http://bit.ly/mBqmIH

They are trying to make the point that Jouett's ride was much tougher than Revere's. I think we can agree that is true

@meanwhile says:Well, you would be wrong. The Declaration of Independence never would have been proposed by John Adams had the Massachusetts colonists not taken up arms against the British

If you are so naive as to think that we would all be english subjects if the Mass militia had lost you are sorely mistaken.

These men were men and the men of Virginia would have made it happen, with or without Paul Revere.

There is no doubt that Virginia would have won freedom.

But the fact of the matter is that the article was not about who had the bigger willy. It pointed out that a local boy risked life and limb to try and save a movement and very few people know it. The stuff about Paul Revere was not to discredit him it was to put context to the times.

" meanwhiles" inability to understand does not make him right.

"There is no doubt that Virginia would have won freedom."

Oh really? The ONLY war effort Virginia has led resulted in an Unconditional Surrender.

The bottom line is that Thomas Jefferson COULD have been a martyr cause, or even have stood and fought as they did in Massachusetts. He chose instead to flee.

His retreat and cowardly fleeing is not nearly as important to the war effort as the actual fighting that took place. THAT is why Jouett is merely a footnote; the story is not that significant.

Believe it or not, Charlottesville, Virginia is not the center of the universe. Sorry.

@meanwhile: why was Jefferson's fleeing "cowardly." What would have have had him do? Stay to be captured? Seems to me Jefferson fleeing the British was the smart (and only) thing to do.

he who fight and run away live to fight another day

The guys up in Lexington and Concord didn't do the "smart" thing, did they?

Jefferson did not a thing for the cause of the revolution after writing the Declaration. And he was NOT the impetus for the Declaration being written, John Adams was. But he did write it beautifully.

He was a terrible governor, and would have done the cause of the war immeasurable good to put up a valiant and noble defense of Charlottesville, simply for the propaganda effect.

It wasn't his smarts that caused him to run away, as there was no reason for him to run away except that he wanted to keep enjoying the creature comforts of Monticello. And I don't blame him. We all know Jefferson had it good up on the hill...

But him fleeing Tarleton was not some smart, tactical move. It WAS cowardly. What else was it? Did Jefferson serve some purpose to the war? His term was ending. The ONLY person he was thinking about was himself.

His capture would have given the colonists another reason to fight. Benedict Arnold was a traitor, that only made the colonists angry. Valley Forge was a nightmarish disaster, that only gave fortitude to our soldiers. Bunker Hill, Trenton, Nathan Hale, there were many examples of bravery and sacrifice in the story of our country's founding.

This story is NOT one of them. I'm glad Jefferson got away. But to claim his escaping was in any way equivalent to the Battle of Lexington and Concord is really laughable.

Yeah, a guy rode in on a horse saying the British were coming. That's about the end of the similarities.... Nobody took up arms against the invading British, they fled away on horse because they were worried more about their own hides than the cause of liberty.

It seems to have escaped everyone's notice that Paul Revere was captured, not once but twice, by the British. He managed to talk his way out of it both times, but he was also considerably slowed down and really accomplished less as a result. A lot of the people he alerted already had heard the news by that time.

I hate to think what this country would have been like without Thomas Jefferson's presidency. Louisiana and points west would be speaking even more Spanish than they are now, for one thing. And we would have a lot fewer states.

Good grief, meanwhile, take a damn pill.

You seem to be dressing up in full armor to attack a hot fudge sundae.

This was a nice little piece that tried to tell us something about an overlooked historical tidbit. I found it entertaining. If you have to go on long rants to criticize the author of the piece, Thomas Jefferson, and Charlottesvillians in general you've got some personal issues to work through.

I ALREADY WROTE ONE ON MAY 13.

yOU NEVER PRINTED NOR REJECTED it

PLEASE ANSWER. I SPENT TIME ON IT AND WILL NOT REPEAT IT.

Justiniano Campa

This was a well written, well researched piece by Rick Britton, kuddos to him!! I am however, distressed by the comments made by "meanwhile," who obviously is a bitter, angry person, with a chip on his shoulder, right in line with some of the other misinformed folks who have been responsible for some of the ugly rhetoric that has been spreading through our country, since dare I say, Barack Obama became the Democratic nominee for president. Even though I am just reading this piece now, thank you as well to the thoughtful insight from the comments above. We can disagree on things without being insulting.....that is what's COWARDLY!! I doubt meanwhile would just sit there and let himself be captured. Jefferson did the only thing an intelligent person would do, plus, he had much left to do with his life, and didn't want his ill wife and young children to be left without a husband and father. Good article Rick!!