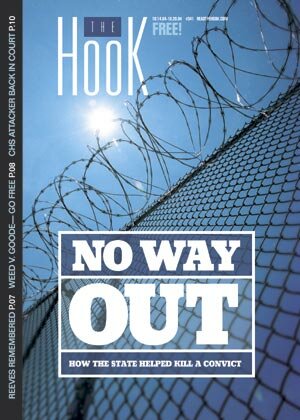

No way out: How the state helped kill a convict

Brunswick Correctional Center

On the night of January 13, 2004, an acquaintance of mine was murdered. His roommate strangled him to death.

This happened in Sussex I State Prison in Waverly. My acquaintance's name was Richard Alvin Ausley, and he was a child molester.

Some would say that Ausley finally got his just deserts. In 1961, he kidnapped and sexually assaulted a 10-year-old boy and left him tied up in the woods, a crime for which Ausley spent 10 years in prison.

Twelve years later, Ausley abducted a 13-year-old boy named Paul Martin Andrews, buried him alive in a box in a rural part of Virginia, and raped him numerous times. After eight days, Andrews was rescued by hunters, and Ausley was sentenced to 48 years in prison. [Andrews' first-person account of the ordeal, "This is his story," was the Hook's January 30, 2003 cover story.]

Ausley was eligible for parole after 30 years, and in 2003, the Virginia Department of Corrections was legally required to set him free. But informed in the summer of 2002 by a reporter of the pending release, Andrews understandably launched a public campaign to prevent his tormentor's return to society. The solution, Andrews explained to the media– including NBC's Today show– was to have Ausley civilly committed to a state mental hospital as a violent sexual predator.

But Richard Ausley was never committed to a psychiatric facility. Instead, he was sent to a high-security prison for especially disruptive inmates and placed in a cell with a convict who had himself been molested as a child. Shortly afterward, Ausley was dead.

This incident has continued to ripple through the prison system: Just a few weeks ago, the Virginia Department of Corrections revised its inmate-housing policy in the aftermath of Ausley's death.

Ausley and I were incarcerated together at one of Virginia's medium-security facilities, Brunswick Correctional Center in Lawrenceville. We were not friends, but I had several interactions with him. Prisons are like small villages. Everyone knows everyone else, if only through borrowing cigarettes from each other.

Like Ausley, I am a high-profile inmate. My 1989 extradition from England set a legal precedent still found in law books; my 1990 trial was featured on Geraldo Rivera's show ahead of the Menendez brothers' case; and fictionalized versions of the crime of which I was convicted are still broadcast as reruns on Court TV and A&E. So I know a little of what Ausley felt as his past was replayed in the media over and over and over again.

I am alleged to have killed my girlfriend's parents because she claimed her mother had sexually abused her and had taken nude photographs of her which she showed to friends. Whether my girlfriend's mother did in fact abuse her is as much in dispute as my supposed guilt as the murderer. I claim I merely covered up the crime after the fact. But whatever my actual role may have been, my motive included loathing of child molesters. So I have considerable sympathy for Richard Ausley's victim, Paul Andrews, as well.

Perpetrators and victims

But I cannot just dismiss Ausley as a monster, if for no other reason than that I knew the man. One day, when the civil-commitment storm was raging at its fiercest in the newspapers, he came to my table in the chow hall, asked to sit down, and said to me, "I just don't know what to do. You know what I mean. Can you help me?"

I certainly did know what he meant, and I knew I could not help him. I told him so, and he shuffled away, a wizened, frail man in his mid-60s, barely 5 feet tall, and to be frank more than a little crazy after three decades in prison.

When I look back on it now, I regret that I let Ausley walk away from my table without at least trying to help him somehow. I could not have prevented his murder, I know, but I failed him as a fellow human being.

At the prison where I met him, there's an entire building full of men like Ausley: rapists and pedophiles within two years of their mandatory release. These prisoners are participants in an innovative program called Sex Offender Residential Treatment (SORT), which provides intensive therapy to prepare them for their return to society. In my view, SORT is one of the best things the Virginia Department of Corrections does, and I only wish it would be expanded.

Sex offenders form one of the largest subgroups of criminals in prison, and I myself have had several of these men as cellmates over the years. Locked in a 7-by-12-foot concrete box with the Ausleys of this world, I have learned to distinguish some character traits they have in common.

Rapists, for instance, tend to be angry and insecure, whereas pedophiles show a marked inclination to be timid, fearful, and dishonest.

Anyone familiar with the psychology of sexual-abuse victims will immediately recognize that second cluster of personality traits: Frequently, children who are molested try to keep their abusers at bay with exaggerated cautiousness, complaisance, and deception.

Why do incarcerated molesters display the same characteristics as their victims? Because the majority of pedophiles in prison were themselves sexually or physically mistreated in their youth.

No, I'm not about to revisit "the abuse excuse," as Alan Dershowitz called this phenomenon with unforgivable callousness. But can we really ignore the fact that– according to federal Bureau of Justice statistics– victims of child abuse are 38 percent more likely than nonvictims to be arrested for a violent crime later in life, and 16.1 percent of male prison inmates admit to having been maltreated as they were growing up?

The actual figure is undoubtedly much higher; many prisoners do not even recognize that they have been abused. When my fellow inmates recall their childhoods, for instance, they brag of leather-belt "whuppings" inflicted by their parents, and other horrors. I have actually overheard a rec-yard conversation between two sex offenders from the SORT program in which the two competed over who had been molested more horrifically as a boy as if this were a point of honor between them!

Other convicts have told me of growing up in detention centers for troubled youths, where older teens raped younger ones on a nightly basis. In their eyes, this was normal, unremarkable, a suitable subject to joke about years later while we had dinner together in prison.

Whether Ausley was abused as a child is something I do not know. But it strikes me as exceedingly unlikely that a person who hadn't been abused would wake up one day and, out of the blue, start sexually assaulting young boys.

Whatever secrets Ausley's childhood may have held, the court did not care when it sentenced him to 48 years behind bars in 1973. He was a monster. But once he entered the prison world, the monster became a victim.

Vulnerable and unprotected

According to former Virginia Attorney General Mark Earley's testimony before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee in July 2002, anywhere from 250,000 to 600,000 of America's 2.1 million prisoners are sexually assaulted by other inmates each year. Pedophiles are probably the favorite target of penitentiary predators because many guards will not help them if they seek protection.

One of the sad ironies of penitentiary culture is that incarcerated pedophiles are frequently subjected to more of the same sexual violence that they experienced in their youths. In the eyes of other prisoners, garden-variety rapists are not so bad and can be tolerated. But molesters like Ausley are beyond the pale and thus fair game for inmate-on-inmate rape.

From what other convicts who did time with Ausley in the '70s and '80s tell me, he indeed had a very rough life behind bars.

In those days, just as today, any young or physically small inmate like Ausley was subject to sexual enslavement by a "prison daddy." Such forced relationships may eventually assume a pseudo-consensual nature; Ausley, however, was intentionally punished by his fellow prisoners and, by extension, the correctional officers who allowed him to be raped. They wanted to hurt him, and they did on a regular basis, for decades, according to my sources.

In the medium-security Mecklenburg Correctional Center in Boydton, in the early '80s, Ausley was granted a brief respite by a gang of young white convicts who protected him and collected regular payment for this service, of course.

Ausley earned his protection money by selling acrylic paintings, which he produced at an astonishing rate and sent to a Virginia gallery that sold them anonymously. Even some guards bought his artwork, as mementos of the monster of monsters.

By the turn of the century, he was transferred to the low-medium-security prison where I met him: Brunswick, with its SORT program. Even here, however, Ausley could not completely escape his past. "Inmates frown on this type of thing," he told the Richmond Times-Dispatch in a jailhouse interview. "There's not a day goes by that I don't hear something whispers, finger-pointing."

SORT participants are all subject to at least some low-level harassment by other prisoners, of course. But a few older inmates remembered Ausley's original crime and confronted him. After his death, another convict told me that he had spoken to Ausley as soon as he arrived at Brunswick.

"You were my bogeyman as I was growing up," this man said to Ausley. "I grew up near where you lived. When my mom wanted us kids to come inside from the back yard, she would tell us, 'Ausley's escaped from jail, boys. You'd better come indoors.' I grew up hating you, man."

According to the convict, Ausley listened and just walked away. No doubt the old child molester had heard it all before.

By sending Ausley to Brunswick, the Department of Corrections presumably intended to provide him with therapy to prepare him for his return to society. That plan, as far as I'm concerned, was both appropriate and intelligent. According to Bureau of Justice statistics, the recidivism rate for released inmates 55 years old and older is 1.4 percent, and Ausley was now in his early 60s.

Contrary to popular myth, rapists and molesters are not completely incorrigible. According to a major recent meta-analysis of therapeutic programs conducted by the Department of the Solicitor General of Canada, only 17.4 percent commit new sex crimes when they leave prison– even without receiving treatment during their incarceration. If they are given therapy, as was the plan for Ausley, that rate of sexual reoffending can drop as low as 9.9 percent. And in the three years that Brunswick Correctional Center's SORT program has been in operation, not a single graduate has committed a new sex crime.

A moment of optimism crushed

In early 2002, things were looking up for Ausley. He had spent roughly two years in the SORT program and was scheduled for release the following year. But unbeknownst to Ausley, that summer, Paul Andrews heard of his pending release and embarked on a highly public crusade to have him civilly committed.

At Brunswick, Ausley had been a known child molester, but with the exception of a few oldtimers who remembered his 1973 trial not a particularly famous one. All this changed when Andrews revisited the nightmarish circumstances of his crime in regular interviews with print and TV journalists. The old pedophile's picture was plastered on the front pages of the state's newspapers at regular intervals. Many inmates devoured the latest Ausley article with the same fervor as Sports Illustrated.

Here at last was someone even a convicted criminal could look down on. As his fellow prisoners worked themselves into a lather over the details of Ausley's crime, the penitentiary hyenas moved in to exploit his weakness. One well-known snitch offered Ausley his "friendship" if the old man submitted to oral sex. Not that the fellatio would be free of charge: Ausley would have to pay $50 for this dubious pleasure. I happened to learn of this particular incident because Ausley refused, whereupon the snitch made good his threat to get the old man in trouble with the prison administration.

But other inmates were the least of Ausley's troubles. On the other side of the razor-wire fence, Andrews had succeeded in making Ausley the poster boy for civil commitment in Virginia. A fairly recent legal innovation, civil commitment provides for the detention of sex offenders in secure psychiatric facilities even after they complete their original terms of incarceration. As of last year, nearly 20 states used this procedure to keep about 2,500 rapists and molesters behind bars indefinitely. Only about 100 of these have been released, because such detainees must first prove to a panel of mental-health experts that they no longer pose a threat to public safety.

From Andrews' point of view, his campaign to have Ausley civilly committed was justified, and I personally sympathize with him. Once again: I am no friend of child molesters. But there is an old adage in the legal community: "Hard cases make bad law." It applies well not only to Ausley's but also to any other sex offender's civil commitment.

After a pedophile or rapist has completed his entire prison sentence, he is in effect tried again on the same charges that put him behind bars in the first place only this time, he carries the additional burden of proving that he can be safely released into society. If he fails that judicial test, he is sent to a facility that's a prison in all but name.

The government sidesteps legal difficulties by pointing out that a trial is a criminal proceeding, whereas a commitment hearing is a civil action. However, that argument does not pass the smell test: Both trials and commitment hearings are held in courtrooms, and in both cases, the defendant ends up locked in a cell. To laymen's eyes, there is no real difference.

What civil commitment does, in effect, is absolve society from figuring out how to reintegrate men like Ausley. The California Department of Corrections recently tried to release a civilly committed sexual predator, Cary Verse, who had been chemically castrated and was considered harmless. The residents of Martinez, a town near San Francisco, organized opposition to his relocation in their community, forcing him, instead, to live in a San Jose motel. That can hardly be considered a case of successful reintegration into society.

Another California sex offender who had completed his sentence, Brian DeVries, had to be housed in a trailer on prison grounds because no town was willing to accept him. And this, in a way, is what civil commitment provides: safe and final disposal of human beings whom no one wants and everyone feels justified in hating.

Virginia provides for civil commitment through the Sexually Violent Predators Act of 1999, but in 2002, the General Assembly had still not provided funding to construct a facility to house men like Ausley.

That changed in 2003, when Andrews succeeded in overcoming the General Assembly's legendary tightfistedness: Legislators finally agreed to build the state's first civil-commitment unit, the Center for Behavioral Rehabilitation in Dinwiddie County, essentially a personal prison for Richard Ausley.

Even after the state had thus guaranteed that Ausley would never see the light of day, the public continued to revile him. When Virginia completed the Center for Behavioral Rehabilitation, the Times-Dispatch vented its righteous anger with the headline "Predators Get Amenities" because the residents of the 36-bed unit would be allowed to play basketball and watch TV, just as in a normal penitentiary.

Switch of plans

Even though the Center for Behavioral Rehabilitation was built because of him, Richard Alvin Ausley did not turn out to be the first resident of this secure psychiatric unit. Andrews had uncovered something else about Ausley's past that made civil commitment unnecessary.

Back when funding for the mental-health unit to hold Ausley still seemed uncertain, Andrews had tracked down Gary E. Founds of Portsmouth. In 1972, Founds had also been sexually assaulted by Ausley. Andrews persuaded him to break three decades of silence about the crime and testify against Ausley. The resulting conviction and new five-year prison sentence meant that Ausley could be housed in a regular penitentiary for the time being. So some other sex offender inaugurated the Center for Behavioral Rehabilitation.

Instead of remaining at Brunswick and continuing in the SORT program, Ausley was transferred to Sussex I State Prison, a security-level-five (out of six) facility specifically designed to house disruptive inmates. Just as puzzling as the therapeutic purpose of civil commitment is the therapeutic purpose of Ausley's transfer to Sussex I, where there are no therapists who work intensively with molesters and rapists.

Department of Corrections spokesperson Larry Traylor told the Hampton Roads Virginian-Pilot that Ausley was transferred to Sussex I because "the latest conviction made it necessary to upgrade his security level." That seems doubtful. Inmates' security-level classifications are a matter of administrative convenience; for instance, my security level is likely to change as punishment for writing this article, thereby justifying transfer to a more restrictive penal environment.

And for sex offenders enrolled in the SORT program, such as Ausley, the security-level classifications do not apply at all: There are several SORT participants at Brunswick who were granted security-level "overrides" so that they could continue to receive therapy here. Whatever the reason for Ausley's transfer, it probably was not security level.

Among the other prisoners at Brunswick, the most popular theory is that Ausley was moved to Sussex I because he was about to escape again, as he did briefly in the '70s. But that cannot be the reason, either. Even if he had been physically able to break out, years of abuse by other inmates had destroyed Ausley's mind. My general impression of him was that he would have trouble finding the door, much less escaping through it.

Perhaps the reason for Ausley's transfer is simply that the Department of Corrections decided not to waste expensive SORT therapy on a man who would obviously never be released. There is, in fact, a waiting list for the SORT program, and this old no-hoper was taking up a slot that another sex offender needed. Perhaps Sussex I was just the nearest prison with an open bed, and Ausley was turfed there for convenience's sake.

Tragic move

If that was indeed how his transfer was decided, correctional administrators could hardly have chosen a worse new home for Ausley. The inmate population consists largely of young thugs who act out violently even behind bars. A small, extremely well-known child molester in his 60s should perhaps have been sent to the geriatric unit at Deerfield Correctional Center, not Sussex I.

Even worse, that facility's administration then placed Ausley, this notorious pedophile, in a cell with Dewey Keith Venable. This 24-year-old inmate, who had been sentenced to 18 years in prison in 2001 for a series of charges that included carjacking, abduction, and robbery, had himself been victimized as a child, by a pedophile named Dennis L. Sewell.

The bomb exploded on January 13, when Venable strangled and beat Ausley to death. After the murder, he wrote a letter to the Times-Dispatch in which he claimed he had warned guards not to place him in a cell with the infamous child molester Ausley. According to Venable, however, correctional officers threatened to put him in isolation unless he agreed to the cell assignment. He also claimed in his letter to "here voices and see shattos."

When informed of Ausley's death, Andrews told the Times-Dispatch, "While I cannot condone what happened to him, I certainly can feel for the young man who is being charged with his death.... The implications of being abused go far beyond the act of abuse. This young man is another example of the path of destruction left in the wake of a sexual predator, and another life ruined by an encounter with Richard Ausley."

In May 2004, Venable was indicted in Sussex County for the murder by strangulation of Richard Ausley. If convicted under the current indictment, Venable faces the death penalty. And in June, Virginia Secretary of Public Safety John W. Marshall ordered the state police to conduct an independent review of the Department of Corrections' actions in this matter.

Marshall undoubtedly fears that Ausley's murder behind bars will embarrass the state's penal system the same way that the John Geoghan case embarrassed Massachusetts. A Catholic priest convicted of child molestation last year, Geoghan was sent to the high-security unit at Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center, where he was killed in August 2003 by a fellow inmate, Joseph Druce, who had been a victim of childhood sexual abuse.

"Prison guards harassed pedophile priest John Geoghan and wrote trumped-up disciplinary reports [that]... led to the frail, 68-year-old Geoghan being... sent to the high-security unit," where he was murdered, Massachusetts Public Safety Secretary Edward Flynn's investigation revealed, according to the Associated Press. "Under no circumstances should John Geoghan have been in the special housing unit at Souza-Baranowski," Flynn told the AP in February.

A change in procedures

If Marshall's state police investigation reaches a similar conclusion in Ausley's killing, then some heads may end up rolling in this state. The Virginia Department of Corrections is not waiting for Marshall's investigation, however. As of August 20, inmates arriving at a new prison will be evaluated to determine their compatibility with potential cellmates.

According to Department of Corrections spokesperson Larry Traylor, the department asked the field to revise procedures and "reiterated issues involved with all bed assignments."

For the inmates he left behind here at Brunswick Correctional Center, Ausley's needless death has been an eye-opening experience, a teachable moment. Prisoners who until now missed no opportunity to make snide remarks to sex offenders have suddenly discovered the joys of convict solidarity.

Now they shout at passing SORT staff members, "Hope you're proud you got Peewee killed, you &#@!" All of a sudden Ausley is known by his old nickname, "Peewee." He's become one of us– who would have predicted that?

But there's a reason that Ausley's story became our own. Back in the real world, the civil-commitment movement is gathering momentum. At the time of Ausley's death, Virginia Attorney General Jerry Kilgore's office had already filed petitions to civilly commit 21 other sex offenders. The Center for Behavioral Rehabilitation has been moved and expanded to 150 beds, and plans are afoot to enlarge it again to hold 250. Within a few years, there will be an entire new system of prisons pardon me, civil psychiatric detention centers for all sex offenders, since none of them can ever be trusted completely.

Eventually, civil commitment will likely be expanded to perpetrators of crimes that are not of a sexual nature but are also considered especially egregious: homicides and malicious woundings, of course, but perhaps also carjackings and abductions precisely the kinds of crimes for which Dewey Venable was sent to prison in 2001, three years before killing Richard Ausley. Given the propensity for violence that Venable has displayed even behind bars, a stay at the Center for Behavioral Rehabilitation certainly seems appropriate.

But why stop there? Unless a marijuana dealer can prove to a panel of state-paid psychiatrists that he will never again sell a single joint, perhaps he should be civilly committed, too. Better safe than sorry!

This sort of thinking has, unfortunately, shaped criminal-justice policies in the United States for the past 30 years. From 300,000 in the '70s, the prison population rose to 2.1 million at the end of 2002. Yet the crime rate today is precisely the same as it was thirty years ago: Seven times the number of prisoners, with nothing to show for it in terms of crime control– not exactly a rousing victory in the war on crime.

But criminal justice policy in the U.S. is apparently not affected by rational cost-benefit analysis. At the end of the day, society just wants the evil bastards gone, no matter what the cost.

Perhaps this was the kind of emotion Venable felt when he strangled the old child molester earlier this year. That young man did not have the option to make Ausley disappear in a civil-commitment facility, so he throttled him instead. He just wanted the evil bastard gone, no matter what the cost.

No matter what the cost.

This article first appeared in The City Paper, a Washington, D.C., weekly.

Richard Alvin "PeeWee" Ausley

STATE POLICE PHOTO

Martin Andrews understandably launched a public campaign to prevent his tormentor's return to society.

Martin Andrews

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

It is obvious that Ausley had an opportunity to work his magic on Soering, as well, if he believes that Ausley was ever a victim.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Paul Martin Andrews

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Richard Alvin Ausley

STATE POLICE PHOTO

Andrews as police found him in 1973

VIRGINIA STATE POLICE FILE PHOTO

Richard Alvin "PeeWee" Ausley

VIRGINIA STATE POLICE FILE PHOTO

Author Jens Soering At Brunswick Correctional Center

PHOTO COURTESY OF LANTERN BOOKS

Freshman-era photos of Jens Soering and Elizabeth Haysom

#