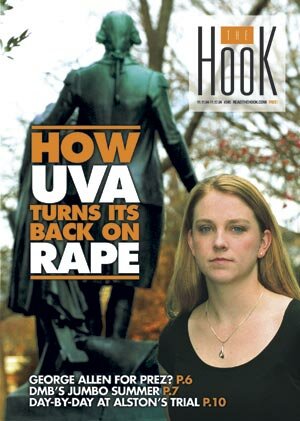

Rape debate: Getting tough on on-Grounds attacks?

The University of Virginia has released a proposed revision of its sexual assault policies just two months after fourth-year student Annie Hylton, who claimed to have been a victim of date rape, came forward to describe her outrage with the university's Sexual Assault Board.

Hylton's experiences, the subject of the Hook's November 11, 2004 cover story, quickly became part of a larger debate over allegedly lenient punishments and sexual assault policies that included confidentiality procedures out of step with federal law.

Hylton risked expulsion by going public with her claim that the Sexual Assault Board failed to adequately sanction her alleged attacker. Although she said he had been found guilty by the Board, he was allowed to remain a student. He has since graduated and has continued to deny his guilt in the incident.

The revised policy would require suspension or expulsion penalties to be considered for guilty students in all sexual assault cases, but would not go so far as to require expulsion for any particular charge.

"I would like to have seen a minimum sanction put on a lot of the charges, not just a 'will consider,'" Hylton says. "There are still a lot of loopholes."

However, Associate Dean of Students Shamim Sisson hails the revised policy drafted by her office, particularly the new requirement that the Board consider expulsion.

"It is certainly a big step," says Sisson. "The procedures that exist right now don't make any recommendation about sanctions."

Sisson defends continuing to allow the Board to impose lesser penalties. A range of sanctions, she says, "acknowledges the difficult nature of these cases."

When more than 400 students staged a protest on Grounds on November 17 (six days after Hylton's story appeared), many wore symbolic gags to express their outrage over another aspect of UVA's policies.

Some saw UVA's confidentiality policy, which Hylton described as a verbal requirement to remain silent about her case, as a "code of silence." That policy bore similarities to a written Georgetown University confidentiality policy the Department of Education recently found to be illegal, according to Dan Carter, a vice president of a watchdog group called Security on Campus.

Carter claimed that UVA's existing policy could even be construed as prohibiting students from speaking with law enforcement. The revised policy clarifies that students cannot be prohibited from speaking to certain people, including law enforcement, at any time. Other people expressly permitted access to case information include legal counsel, family members, as well as medical and mental health professionals who are in a "treating relationship."

Sisson says that while UVA never explicitly prohibited students from speaking with any of the parties now mentioned in the revised policy, confidentiality expectations were not spelled out.

"What we've done in the past is simply to ask people to draw a circle and not extend past that," she says.

Dean Sisson says that UVA had already begun overhauling its policy by the time Hylton spoke out, and that the University has always disclosed hearing results to the individuals involved– a procedure that is required by the federal Clery Act, which governs crime reporting by colleges. UVA's revised policy is explicit: "Both the complainant and the accused student shall be informed of the outcome of the hearings process."

Another policy change is creation of a lesser charge of "sexual misconduct," which Sloane Kuney, chair of UVA's Sexual Assault Leadership Council Chair, calls a "step backward."

"These guidelines are not set up to create a culture of affirmative consent," says Kuney. "The absence of 'no' is not the presence of 'yes.'"

Some who defend the push for creation of lesser charges in sexual assault cases point to the fact that many alleged date-rapes involve heavy alcohol consumption by both parties as well as a lack of physical evidence. In certain cases, alleged perpetrators have even claimed that the charges were concocted after a consensual act.

The revised policy, made public January 13, will be finalized before the end of this semester, says Dean Sisson, who encourages members of the University community to send their comments and recommendations to by January 31.

Despite the changes, Hylton says she remains frustrated with the revised policy's approach to confidentiality.

"It just seems like they're trying to check the boxes and not worry about the students," she says. "The confidentiality [policy] seems to still not address what you can do after the hearing."

Kyle Boynton, president of a UVA student group called Sexual Assault Peer Advocacy, believes that students involved in sexual assault cases should also be allowed to communicate with friends– not just officials in a "treating relationship."

"Its really important to remember that friends can be in a 'treating relationship' with a student," Boynton argues. "It's so important that we protect a survivor's right to speak out about what happened to her."

Boynton remains skeptical. "The real test is going to be whether somebody found guilty of sexual assault is suspended or expelled from the University," Boynton says. "Are people who commit sexual assault going to be held accountable or not?"

Annie Hylton on the cover of the Hook.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#