Cold clues

By Katie Hamlin

Only my mother called me more frequently then they did in the fall of my first year in Charlottesville. I woke many a morning to a phone call from a cold study coordinator, calling, always chipper, to check in and make sure that I didn’t have the slightest sniffle.

Week after week, my resounding negative replies began to make me feel as if I were stalling scientific progress. The patience of the nurses astounded me, but I knew that if I ever answered the phone with a muted hello they would fulfill their call to duty.

I am not alone in my attempts to make some money from the small misery that goes along with the average cold. There’s a quiet industry in Charlottesville– one that hotels don’t like to talk about, one that seems to have escaped the Chamber of Commerce brochures: medical studies. In particular, colds have kept Charlottesvillians theorizing since Thomas Jefferson bragged that he avoided illness by soaking his feet in cold water every day.

I will admit that I’ve become a kind of darling of the cold study community. It’s a symbiotic relationship really; I give them my used tissues, they reimburse me with money– to go buy more tissues.

After having participated in three colds studies, I feel as if I am an expert, though I have yet to have participated in an experimental cold study. Experimental studies are usually closely monitored and often entail deliberate exposure to the cold virus; participants are then treated with either the study drug or a placebo. This highly controlled endeavor typically happens at a hotel where an entire floor may contain the quarantined participants who are left to their own devices to spend between three and seven days– sometimes more– watching free cable and talking on the phone.

Back in 1999, when he was a UVA student writing for The Declaration, local reporter Austin Graham wrote about the $1,500 he made for nine days of boredom.

“You don't realize how important the little things in life, like filling your gas tank or watching strangers trip on stairs, are until they're taken away from you,” wrote Graham. “My personality quickly took on the bland, unoriginal nature of my room's wallpaper, and once that happened, James Joyce and my laptop didn't get touched.”

Another UVA student, now a Hook intern, Laurie Ripper explains the attraction for students who don't have a swanky trip planned for spring break. They can "1) sit around all day and get paid $400, or 2) sit around all day."

I have always opted to participate solely in natural cold studies because these studies don’t make you sick; you receive the experimental drug or a placebo only if you happen to become sick. Often these studies take a group of healthy participants and attempt to follow their health over a period of months; the participant receives the drug or placebo at the first sign of a cold. Another variation of these studies is for volunteers to join the study immediately if they happen to be sick.

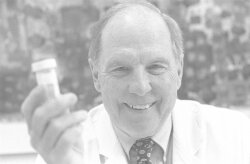

While cold study headquarters can vary, Cobb Hall, located near the medical school, is mission control for UVA professor of internal medicine Dr. Jack M. Gwaltney Jr., the man a recent issue of The New Yorker calls “the world’s foremost cold expert."

So I headed over to Cobb, where research coordinator Pat Beasley was happy to speak with me about the studies, even going so far as to decipher whether in my first study I was on a placebo or the real deal. All the information was there– they can’t throw anything out. The rows of institutional green file cabinets archive everything– even the number of tissues a particular volunteer may have used in a given week.

With all this evidence, it would seem that surely I was looking at a museum of progress. There have been thousands at UVA and in other university communities who have bravely joined me in the ranks of tissue saving and pill popping. The April 22 cover story in Time calls us "human guinea pigs."

What then, has been discovered? Whom have I healed?

This past fall I answered my annual call to duty by participating in a natural study for a developing drug, Picovir. Dr. Frederick Hayden, a colleague of Gwaltney's, spearheads UVA's participation as one of over 200 study sites for ViroPharma Inc. of Exton, Pennsylvania. (With the likelihood of a vaccine dim, government money has diminished, and pharmaceutical companies now provide the bulk of cold study funding.)

The road to FDA approval of a drug is a long one, navigated by many companies attempting to find the wonder drug that will enable millions of us to have one less excuse to call in sick. According to Dr. Gwaltney, the average drug takes at least five years to pass FDA standards.

Dr. Hayden made headlines in December when he announced that Picovir was able to shave a day off the duration of cold symptoms.

Some scoffed that that wasn't a big deal. But while colds aren't as sexy as gene therapy and sheep conceived in petri dishes, they're society’s most common health problem. Cutting a single sick day could save billions in lost wages and lost productivity for the world economy. Moreover, Picovir might provide an alternative to antibiotics– overuse of which has come under fire for fostering strains of drug-resistant bacteria.

Earlier this year, Picovir made headlines again. But this time it was a setback for Hayden. On March 19, an FDA panel voted 15-0 to keep Picovir away from the sniffling public– at least until further study.

"I don't think the risk/benefit ratio is there for such a common disease that is not life-threatening," said panelist Dr. Sharilyn K. Stanley.

Other concerns included an allegedly insufficient number of minority study participants– not to mention the fact that two women taking Picovir and birth control pills got pregnant.

Hayden says he isn't dismayed, though. Picovir will be back, and he says he's also studying a nasal spray called Ruprintirvir, or AG788.

Meanwhile, back at Cobb, Dr. Gwaltney continues to hold out hope for a “cocktail drug”– a mixed prescription containing an anti-viral ingredient accompanied by an antihistamine and ibuprofen. Despite what happened to his colleague at the hands of the FDA, Gwaltney says he's certain his cocktail will eventually hit the market.

Having collaborated on over 500 trials and experiments in his 40 years of work, Dr. Gwaltney had some very simple answers for my subtle hints about the futility of his life’s work.

“More has been learned in the past 50 years,” he points out, “than was known in the past 50,000 years put together.”

Still, I couldn’t help but feel that one of his life’s pursuits, a cure for the common cold, was an impossible dream. Dr. Gwaltney referred me to Webster’s Dictionary and its definition of “cure," a word that I had so freely wielded. The definition: “recovery or relief from a disease.” Scientists, it seems, are not necessarily attempting to prevent colds; they want to alleviate the degree and duration of cold symptoms.

Indeed, the last 50 years have been pivotal. In 1956, the first cold virus was discovered; 30 years later, Michael Rossman of Purdue University discovered the virus’ structure. But although scientists continue to uncover the mysteries of cold-causing viruses, it seems the more they learn and understand, the more they realize how complex colds are, and why one single cure is unlikely to be found.

According to the American Lung Association, there are over 200 different cold viruses, with an estimated 35 percent caused by one particular class of viruses, the Rhinoviruses. With this information, many cold studies attempt to focus on the development of drugs to attack this particular class of viruses.

Information doesn’t come cheap; Dr. Gwaltney estimates that the studies for a typical drug in development run about $500,000. Hotel bills must be paid.

For instance, according to state procurement forms, the Holiday Inn on Emmet Street charges as much as $84 a night for cold study participants. The Omni charges $88, while the DoubleTree keeps fees under $80. Meanwhile, the Holiday Inn on Fifth Street is wheeling and dealing– it charges just $48 a night for cold studies and throws in a free room if an entire floor is rented.

Our efforts to discuss the economic bounty with hotel managers were unsuccessful, and our query to the local chamber of commerce turned up little more. "I've never had anyone ask the question," replied chamber spokesperson Larry Banner when we asked what cold studies do for the local economy.

Even natural cold studies, which don’t require a hotel-based quarantine, involve lots of money. For instance, for one study I received $20 a month— no small change for just existing. Plus, when I finally did get sick and took the medication, I received another $150.

So Gwaltney and Hayden don't have a cure. But they do have a website, commoncold.org. Besides dispelling lots of myths– such as the one about "starving" a cold– they explain everything one needs to know. On his website and in person, Dr. Gwaltney advises that you wash your hands and keep them out of your eyes and nose.

So is a common cold cure a vain dream? While Dr. Gwaltney urged me to cut the scientific community some slack, I’ve lost some of my original glorified sense of duty, and my urge to participate in the exciting progress of science has all but dried up.

Despite this, I’ve come to expect and depend on the supplementary income as well as the friendly phone calls and visits to Cobb Hall or student health. I mean, if you’re going to be sick anyway, you might as well get paid for it and have a couple of people fawning over you and your snot to boot.