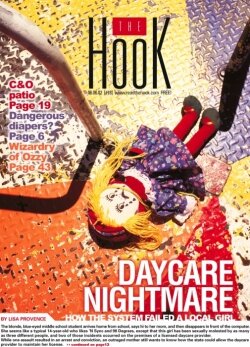

Who's watching the kids?

The blonde, blue-eyed middle school student arrives home from school, says hi to her mom, and then disappears in front of the computer.

She seems like a typical 14-year-old who likes ‘N Sync and 98 Degrees, except that this girl has been sexually molested by three different people, and two of those incidents occurred on the premises of a licensed daycare provider.

While one assault resulted in an arrest and conviction, an outraged mother still wants to know how the state could allow the daycare provider to maintain her license.

Abandoned baby

Emily Johnson– not her real name– has not had an easy life. Her adoptive mother, Bernice Johnson-– also not her real name– was working part time as a clerk at Martha Jefferson Hospital in 1988 when a woman came in who had syphilis, a three-month-old baby, and was pregnant again. The woman reappeared when Emily was two days old, claiming that the baby was having seizures.

“She was trying to dump her,” says the elder Johnson. “She had no income, no insurance.”

Johnson describes Emily’s father as a drug dealer and her birth mother as a “con artist” who’d spent time in the penitentiary.

Johnson and a nurse took turns keeping Emily for a couple of months when the mother didn’t take her back. Ultimately, Johnson, a single woman who’d never been married, was keeping her all the time and soon realized she wanted to adopt Emily.

“I’d always loved babies,” says Johnson. “When she was 13 months old, I decided I wasn’t spending all my money when her mother could take her back at any time.”

When Johnson needed childcare for Emily, she turned to the Department of Social Services (DSS), which had helped her with the adoption, and to a list of licensed and voluntarily registered daycare providers published by Children, Youth and Family Services, a nonprofit organization.

All went well, or so she thought. But after Emily had graduated from daycare to elementary school, the child began revealing things.

Johnson remembers that day in 1998 when she got a call from a school guidance counselor informing her that her daughter had been raped at her daycare provider’s home three years earlier– when she was just six years old.

“I got hysterical,” Johnson recalls.

She explains that Emily didn’t say anything sooner because her attacker, Roosevelt Howard, had threatened to “rearrange her face.” He was the brother of the daycare provider, Margie Baucom, who was running a state-licensed facility. Howard was listed on her license application as her substitute.

Now serving a sentence for the crime at Deerfield Correctional Center in Capron, Howard, 54, was unavailable for comment for this story.

Baucom says she had asked her brother to help out because he “was good with kids.” He passed a criminal background check, and when his name was sent through the state’s central registry of people who have abused or neglected children, he came out clean.

When Charlottesville Detective Garlin Mills, who handled the case, interviewed Howard on April 8, 1998, Howard initially denied any inappropriate touching of Emily, according to a transcript of the interview. Then Mills told Howard that a doctor’s exam had shown Emily’s hymen was broken. Howard denied having intercourse with the child but finally confessed that “it might have been” that his hand touched Emily’s vagina and that his penis was out and the child touched it.

“As a rule,” says Mills, “children 10 and under do not lie about being sexually abused.”

Howard was arrested and charged with rape, aggravated sexual battery of a minor, and animate object penetration. The two former charges were dropped in a plea bargain, and Howard was sentenced in March 1999 to 20 years in prison, with 10 years suspended.

The nightmare continues

For Bernice Johnson, the prospect that Roosevelt Howard raped Emily was just the first in an escalating spiral of horrifying information. Emily soon revealed that another molestation had happened at Baucom’s house a year earlier.

Emily told her mother that a 13-year-old boy who had access to Baucom’s house had locked her in a bedroom and forced Emily to rub lotion on his penis.

When Bernice reported this incident to the Department of Social Services, she claims she was told by social worker Faye Crutchfield that no legal action was possible because the juvenile, whom The Hook will abbreviate as "R–-" because he's a minor, was already in a program in Richmond for sexual offenders. Citing client confidentiality, Crutchfield declined to comment on Emily’s case.

Standard DSS procedure is to call the police when it receives word of sexual abuse, but details are murky about whether the police were actually advised about this case. Johnson maintains that police never interviewed Emily or her about this incident.

A mother’s outrage

Johnson was incensed that Margie Baucom was allowed to keep her daycare license after two allegations that sexual abuse occurred in Baucom’s home.

“People who go to the trouble to find licensed day care do that so their children will be safe,” Johnson says.

Paula Zirk, the inspector with the Division of Licensing Programs who investigated Johnson’s complaint, says the decision to let Baucom keep her license was “difficult.”

One reason Baucom kept her license was that by the time Zirk investigated the alleged rape in late 1998 and early 1999, Roosevelt Howard was already out of the house.

He’d already confessed, accepted the plea bargain, and was a few months away from being sentenced. While out on bail, he’d been ordered to stay away from children under age 18.

Chris Fracher, regional licensing administrator and head of the Verona office of the Division of Licensing Programs, explains why a daycare license wouldn’t necessarily be revoked when there’s been an assault in the home: “You can’t fault Mrs. Jones because Mr. Jones is off in prison.”

As for the second allegation, that R–- had molested Emily, Zirk wrote in her report that the complaint was investigated and “deemed credible.” But again, no action was taken because R–- was already “locked up” in a residential treatment program.

According to the compliance agreement between the Division of Licensing Programs and Baucom, neither Howard nor R–- could enter the Baucom home as long as Margie had a daycare license.

Still, doesn’t it look bad that two major incidents may have occurred in Margie Baucom’s house?

“We couldn’t prove she had knowledge of this,” Fracher says.

That doesn’t satisfy Johnson.

“This licensing thing really drives me crazy,” she says. “It really doesn’t mean anything.”

Disbelief

Margie Baucom disputes that R–- ever did anything to Emily, and she says Inspector Zirk told her the accusation was “unfounded.” The alleged incident occurred over the Christmas holidays when there were so many kids– a licensed home daycare provider is allowed to keep up to 12– at Baucom’s house that she doesn’t see how R–- could have had the opportunity.

Zirk’s investigation mentions that another juvenile was also in the locked bedroom at the time of the alleged incident. Baucom says this child “tells everything,” so she was doubly amazed she never heard anything of it until a year later.

What clinched Baucom and her husband Dwayne’s disbelief was that Emily claimed R–- wore briefs.

“I said, 'That’s a lie,'” Baucom recounts. “R–- doesn’t wear briefs. He calls them ‘whitey-tighty.’”

However, in her report of the allegations, Zirk notes quite clearly that Emily described the clothing as boxers, and “this was confirmed by [name blacked out].” Zirk adds in the report that she found Emily “very credible.”

The report also says that “there may have been other incidents” and notes that R–- “danced naked in front of a window.”

As for why R–- was in a treatment program at Genesis Charter House in Richmond a year after the alleged molestation, Baucom says something happened at his school where “a little girl sat on his hand.” Her husband adds that there were “several girls at school he was supposed to have touched.”

Dwayne and Margie Baucom’s neat living room in a duplex off Rio Road is quiet since Margie stopped taking daycare children after a stroke in August 2000. She and her husband say that R–- is nearly 18 and incarcerated again, this time for selling drugs.

Dwayne was told that R–- was sexually molested, perhaps by foster parents, before R–- was four years old, and says, “He’s going through a lot of emotional problems.”

Although victims of abuse sometimes become abusers themselves, the Baucoms continue to doubt Emily’s accusation against R–-.

Painful acceptance

The charge against Margie Baucom’s brother, Roosevelt Howard, is much more difficult for her because he confessed. Her husband says, “We had a real hard time believing this because we’d never seen [signs of abuse].”

“If you can’t get your relatives to help you, who are you going to get?” asks Baucom. “I trusted my brother with my own kids.”

When she heard about her brother, “I was angry,” recalls Baucom. “I was in tears. I couldn’t believe it.” Baucom looks upset just recalling that time.

Her husband attempts to comfort her. “You didn’t do anything wrong,” Dwayne reassures her.

Even four years later, Margie Baucom is troubled by her brother’s actions. “A lot of people had trusted him with children,” she says.

However, she’s convinced “my brother did not bother anyone else’s children.”

Adds Dwayne, “We’ve gone through hell because of what happened, and we didn’t have anything to do with it. I don’t understand why [Margie’s] license would be affected. She didn’t do it.”

Signs something is wrong

The events at Margie’s house were not the first time Emily had been molested in a childcare provider’s house– nor the first time a provider denied that anything happened.

One Sunday in 1991, when Emily was three and a half and strapped into her car seat on her way to another babysitter’s house, she told her mother, “I don’t want to go to H––‘s.” [This provider, who was never charged, spoke with The Hook on the condition her name not be used.]

“I didn’t pick up on those clues,” says Johnson, even when Emily went "berserk" about going to H––‘s house. Finally, the preschooler told her mother what had happened with H––‘s 17-year-old son.

Johnson says she believed Emily and took her to the Department of Social Services, where social worker Faye Crutchfield, who later was involved with the DSS investigation of the Baucom home, escorted Emily into a room with a two-way mirror. Johnson describes the room as having a dollhouse with blonde dolls that looked like Emily.

“Let’s pretend this is H––’s house,” Crutchfield reportedly told Emily. “Show me where [the son’s] room is. Can you show me what [the son] did to you?”

Based on Emily’s responses, Johnson says, Crutchfield determined there was “reason to suspect” that abuse had occurred.

Emily also saw psychologist Ruth Ball, and at her office Emily drew pictures of the son’s penis, according to Bernice. Ball did not return calls from The Hook, and Crutchfield declined to be interviewed for this article.

H–– claims that her son wasn’t even living with her when the incident allegedly occurred; however, they went together to the police station to be interviewed. Of the accusation, H–– declares it “unfounded.”

Emily description of H––‘s son’s room as having a white bed convinced H–– the story wasn’t true. “I didn’t even own a white bed,” she says. Furthermore, her daycare kids weren’t allowed upstairs where the bedrooms were.

However, Johnson says that once when she was picking Emily up she saw a little girl coming down the steps from upstairs.

“I was licensed, I guess, through Social Services,” says H––. “The kids I had came through Social Services, and Social Services paid me. They’re very strict. I had a criminal background check, and I had no record. I’d never been in courts except to get my son’s license.”

After the son was accused of molesting Emily, all of his mother’s DSS-referred kids stopped coming.

“It really affected me,” says H––, who now lives in an apartment with her collection of stuffed animals. “That was all my income gone-– over $1,400 a month. I had to go into the hospital for depression. It’s upsetting me now.”

Her son, now 28, just got married.

And H–– is convinced that Johnson lied about her son. “I think something was going on in her house with that man who was living with her,” she says.

The man, Bernice’s housemate, rented a room from her and lived with her for about eight years. “There is no way in hell that happened,” responds Johnson. “There is absolutely no way. You can ask Dr. Ball.” Ball, the psychologist who saw Emily, did not return calls from The Hook.

Dwayne Baucom also notes the odds of Emily’s being abused three separate times: “I find it hard to believe she has sexual problems with every man she runs into.”

“Who cares what he believes?” retorts Johnson. “It is very hard to believe, but I know it happened. Dr. Ball, Faye Crutchfield, and [Detective] Garlin Mills believed her.”

Johnson claims that after the incident, H––‘s son’s name was listed on the DSS Child Protective Services’ central registry of those suspected of child abuse and neglect. Names can be added to the registry even if the finding of abuse isn’t provable in court.

The Hook was unable to verify whether H—‘s son’s name is, in fact, listed on the registry. The local Department of Social Services, which could check, isn’t talking, and anyone trying to find out if a suspected abuser’s name is listed has to obtain a release from the suspect.

So why have the registry? It’s primarily a safeguard for other agencies or employers. Typically, a person seeking employment or who wants to be a foster parent signs a release allowing his or her name to be run through the central registry.

The severity of the offense determines how long an individual’s name is kept on the registry– time can range from three years for minor incidents like bruising, to 18 years for offenses such as physical abuse resulting in fractures or the rape of a child, according to Betty Jo Zarrif at the central registry in Richmond.

The registry receives over 100,000 requests for searches annually. While Zarrif doesn’t know the total number of names in the registry, names of 7,435 caretakers who were subjects of “founded”– or credible– allegations of abuse and neglect were added to the Virginia registry in the past fiscal year.

And “caretaker” doesn’t mean only daycare providers: the list includes parents, teachers, babysitters, and anyone else suspected of abusing or neglecting children, even if criminal charges were never filed.

Loopholes in licensing

As Emily Johnson’s story illustrates, a childcare license is no guarantee that a child will be safe in a particular facility. And The Hook discovered other lapses that allow juvenile delinquents present in the home of providers to avoid detection.

A state license is required in Virginia for providers who keep between five and 12 children, the most that can be kept in a home. For five and fewer kids, no license is required, but providers often sign up for voluntary registration with Children, Youth and Family Services.

To be licensed, a daycare provider must be certified in first aid and must take eight hours of training every year. The applicant must have a criminal background check, and her name must be checked against the central registry, as must the names of any other adults living in the home.

Juveniles between 14 and 18 years old living in the home, however, are a different story. Teenagers’ criminal records cannot be released to the public.

“I suspect you could have juvenile offenders in the home,” says Verona-based licensing head Chris Fracher. “You could have a 17-year-old in the home with a criminal record, and we wouldn’t know unless the provider volunteered the information.”

The names of juveniles are run through the central registry, says Fracher, but if a juvenile has a criminal conviction for something like armed robbery, his or her name won’t appear in the registry because such offenses don’t relate to child abuse or negligence. A conviction for an offense relating to child abuse or neglect would be on file, but the general public would not be able to find that out without signed permission from the youngster.

R––, the 13-year-old sexual offender who was sent to a treatment program at Charter Genesis, completely slipped through the cracks.

“A 13-year-old is not required to go through the central registry or have a criminal background check,” says Fracher, because 14 is the minimum age for a registry check.

“If we had knowledge that someone was ever on the registry, they’d be barred from working with children,” says Fracher. He adds, “There cannot be someone with a criminal record living in the home.”

To Bernice Johnson, the fact that 13-year-old R–- was already in a program for sexual offenders when Emily described the lotion incident meant “my child was not his first victim,” she says.

David Dyer, head of Child Protective Services at Charlottesville’s DSS, refused to comment specifically on Emily’s case, but he says, “We wouldn’t necessarily have a record of a juvenile assaulting a juvenile.”

However, in this case, DSS did know about R–-‘s proclivities. Between the blacked out names in the Division of Licensing’s investigation of R–-‘s assault on Emily is a notation by someone at DSS saying that she doesn’t feel that R–- “should be around daycare kids while unsupervised.”

The message, it seems, reached DSS’ licensing division too late.

Prying the records loose

DSS in Charlottesville refuses to confirm details of Emily’s unfortunate history because of confidentiality requirements.

However, the DSS division that issues daycare licenses, the Division of Licensing Programs, is more forthcoming with information about daycare providers.

Fracher says that most records regarding daycare providers are shared “freely” with parents and others making inquiries, although an interesting exception comes up when The Hook requests the records on Margie Baucom under the Freedom of Information Act.

When an allegation arises not from a parent but from the Child Protective Services branch of DSS, it is excluded from public scrutiny, says Fracher.

That means a parent checking up on a potential daycare site to see if there have been any charges of child abuse would be denied the information if DSS were the sole source of the complaint.

Because Emily’s mother filed her own complaint with the Division of Licensing Programs in December 1998, it was the record of that investigation The Hook was allowed to see– with names redacted.

The nonprofit private agency Children, Youth and Family Services provides a listing of both licensed and voluntarily registered child-care providers in the area for $5. The current CYFS list notes that “licensure or voluntary registration are minimum guidelines and do not guarantee quality childcare.”

With the huge demand for quality child-care, the low pay and long hours do not always draw the brightest and the best.

“They do not always have common sense or understand the risks in taking care of children,” Fracher says of providers.

He describes the larger mission of the Division of Licensing: “We want to encourage the availability of quality childcare. We try to weed out the worst of the worst, and prop up those who are on the fence.”

Here’s something else for parents who use licensed daycare providers to consider: if a sexual assault occurs at your provider’s home, there is no requirement that parents of other children there be notified.

“The burden is on the provider,” says Fracher. “We would not broadcast there was a founded allegation.” While the complaint and compliance plan are all public information, inquiring citizens have to approach the Division of Licensing themselves to get it.

So did Margie Baucom advise the parents of other children she was keeping that a person accused of child abuse had access to her home?

She says she did not.

“I felt like since R–– wasn’t here and Roosevelt wasn’t here, I felt like there was no need,” she says.

In the case of H––, who was not licensed by the state but who was paid by DSS, DSS did notify the parents of the children H–– kept of Emily’s complaint.

According to Bernice Johnson, the agency wrestled with whether to tell the other parents about Emily’s allegation that H––‘s son molested her.

“They told me that on the one hand it would deprive her of her livelihood,” says Bernice. “On the other hand, they could be sued if it happened again and they knew.”

Today, neither Baucom nor H–– keeps children in her home.

Impact on Emily

Emily was admitted to Charter Hospital in Richmond twice in November and December 1998, when she was 10 years old, for suicide crisis treatment.

Roosevelt Howard’s trial that year sent Emily “over the brink,” says her mother. When it seemed that Emily might have to testify– before Howard accepted the plea bargain– Johnson, Emily, and the psychologist walked to the courthouse to prepare Emily for appearing at the trial.

In February 1999, Emily was admitted to Bridges Treatment Center in Lynchburg and wasn’t discharged until 16 months later, in June 2000. She gained 60 pounds, which Bernice thinks she did purposely to become unattractive to males.

Today, Emily has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. A psychologist told Bernice that the illness can be brought on by trauma such as sexual abuse.

Emily is on three medications to control mood swings and hallucinations. She sees a psychologist once a week and a psychiatrist once a month.

On the bright side, however, Emily has lost most of the weight she gained, does well in school, and has a boyfriend. But, “Every once in awhile, she gets depressed and suicidal,” her mother says. Emily declined to be interviewed for this article.

“I’ve been thinking about [the abuse] and the problems it’s caused us,” says Bernice. “She doesn’t trust people, and she holds it against me because I didn’t protect her. I don’t know if it’ll ever go away. Dr. Ball says so many bad things happened to her that she had no control of that she fights for control now.”

Adds Bernice: “She was a trusting kid.”

(sidebar)

Tips for choosing childcare

We’re a society that demands safety, no matter how uncertain life is. We can do everything experts advise– and yet bad things can happen. We take a risk every time we get in a car, and every time we leave our children with others, even family members.

About 100 cases of child sexual abuse are reported in Charlottesville each year, estimates Detective Garlin Mills, who’s in charge of investigating sex crimes in the city. The majority of the cases are unfounded, and very few involve daycare providers.

“Most of the time, it’s family members,” says Mills, adding that the stereotype of the stranger in the bushes waiting to abduct a child is misleading. “Usually it’s someone you know.”

Sue Houchens is in charge of daycare and funding for Charlottesville’s Department of Social Services, a program that makes payments for childcare for those trying to get off welfare. She advises parents not to choose daycare just because it’s convenient or cheap.

One important indicator is how many kids are kept at the house. The 12-child limit for a licensed provider is set for a reason.

“If there are 20 kids there, ask questions,” Houchens suggests.

Other adults hanging around are something to be wary of, says Houchens. A weapon lying around is definitely not a good sign.

“And if a provider doesn’t want you to drop by, that’s a red light,” says Houchens.

Children, Youth and Family Services and the Department of Social Services provide brochures and advice on choosing quality childcare. And who’s to say a licensed provider ultimately will be any better-– or worse-– than grandparents or a neighbor?

“Abuse or neglect can happen in any home,” says Houchens.

And like any other parent, she admits, “I’m scared to send my two girls over to other people’s houses without knowing them.”