>> Back to The HooK front page

COVER- She's dying: His drug could save her

Published February 24, 2005 in issue 0408 of The Hook

By COURTENEY STUART

Mary Jane Gentry is going to die, and the UVA Health Sciences Center, which has saved countless lives, has pulled away the experimental drug that might save her.

"It was a ray of hope," she says, "and then they stopped it."

When she was diagnosed 18 months ago with an aggressive case of "Lou Gehrig's disease," Gentry knew it was a death sentence. Doctors told her she had less than three years to live.

Desperate, Gentry-- herself a nurse at UVA-- agreed to participate in a novel drug study. After eight weeks, she was thrilled by a sign that the disease not only seemed to have slowed, but might actually be reversing. She could suddenly move her left hand, which had been useless for several months.

And her experience wasn't isolated: nearly half of the study patients reported noticeable improvements in their condition while none reported side effects.

So why did UVA halt the study?

Wrenching news

Mary Jane Gentry thought she'd put the finishing touches on her new life in the early 1990s. She'd gone back to school to become a registered nurse and had graduated from PVCC with honors. She'd worked her way up to become the clinical director of a dialysis unit at UVA Medical Center. But in the summer of 2003, Gentry, then 45, noticed some weakness in her legs.

"I'd gone to the beach with my daughter," she recalls, "and I noticed how hard it was going up steps."

She blamed an old knee injury, but when her strength didn't return, she made an appointment with her doctor. The exam raised a red flag.

"I couldn't lift my toes," she says.

As a nurse, Gentry knew that could be a sign of a serious problem. "I was thinking MS," she says, referring to multiple sclerosis.

At first, doctors assured her that the problem could be as simple as a pinched nerve. "They told me there was a one in 300,000 chance it was something serious," she says. But to put her mind at ease, they suggested additional exams.

In early August, she underwent a battery of tests, including extensive blood work, multiple MRIs, and finally a test to measure nerve signals. When she hadn't heard back from her doctors by Friday, August 8, 2003, she prepared to leave for a family vacation at Smith Mountain Lake near Roanoke.

"I figured I'd just get the results when I got home the next week," she says. No news, she hoped, was good news.

But an hour before she was to leave, the phone rang.

"The doctor said I needed to come in right away," says Gentry, weeping, "and I needed to bring someone with me."

A medical discovery

Gentry is suffering from ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Like MS, it's a degenerative neurological disease. But unlike MS, ALS always causes complete paralysis, and it doesn't go into remission. Two years after baseball legend Lou Gehrig delivered his "luckiest man on the face of the earth" speech at Yankee Stadium, he died from the disease.

Gentry didn't know it when she received the devastating diagnosis, but for a decade a pioneering neurologist had been working to develop a treatment. The doctor was getting ready to launch the first phase of his study in humans, and he happened to be at UVA. The drug was an already developed but unused compound.

"It was just sitting on the shelf of a German drug company," recalls that neurologist, Dr. James Bennett. He believed the drug might help stop-- and perhaps even reverse-- the nerve cell damage that is characteristic of ALS.

Bennett says that autopsies of ALS patients have shown higher than normal nerve damage from "free radicals."

While free radicals may be best known for their role in aging (various "anti-oxidant" vitamins promise to halt their harmful effects), Bennett believes they play an even more insidious role in ALS.

If he could find a way to stop free radical damage, he thought that perhaps he could slow the disease's progression.

He knew about Mirapex, a drug that had been used to treat patients with Parkinson's disease. It is a "super anti-oxidant" that can absorb more varieties of free radicals than any over-the-counter drug. Even better, it specifically targets mitochondria, the cell structure from which free radicals are released.

But giving ALS patients doses high enough to get positive results would cause devastating side-effects: nausea, disorientation, and, eventually, psychosis.

The drug on the German shelf is pramipexole, the chemical mirror-image of Mirapex. Both have the ability to scavenge free radicals, but the reverse chemistry meant pramipexole might not have the same devastating side effects. He believed it could be useful in treating ALS.

But getting a drug from lab to patient is a complex process.

"I spent three years trying to convince the German company and its American counterpart to develop the drug," says Bennett. Despite the high profile of Lou Gehrig, ALS is an uncommon disease. About 30,000 people in the United States have it at any given time, and drug companies seem to consider it an "orphan disease." With so few potential users, the costs to develop a marketable drug might never pay off.

Finally, Bennett says, "I made the command decision to develop it on my own."

Through the regulatory thicket

Though the German company held the patent on the compound, Bennett audaciously filed a patent application with the UVA Patent Foundation based on the compound's use-- for ALS treatment.

"They couldn't believe I'd patented their drug," he laughs, though he says the company never opposed the move.

He hired a Canadian laboratory to synthesize the drug, and in December 2000, he filed what's called an Investigative New Drug request with the FDA.

But it wasn't smooth sailing.

"The chemical wasn't pure enough," says Bennett, so the Canadian company spent two years improving the formula. Eventually, it achieved 100 percent purity.

While Bennett was cutting through red tape, Gentry's condition was worsening-- rapidly.

"It's terrifying," she says. "Every day, every week counts for me."

By September 2003, only a month after her diagnosis, she was using a cane. In October, she needed a walker, and by January 2004 her legs had weakened so significantly that she required a wheelchair. Once an avid swimmer and boater, she now lives at The Laurels, a nursing home near Route 29.

Bennett ramped up his efforts. He'd received FDA approval to begin testing, but federal law required him to secure permission from an Institutional Review Board, an ethics committee that approves any research conducted on humans.

"It's to avoid awful things like Tuskeegee," explains Bennett, referring to a notorious mid-20th century study in which doctors allowed African American men to die slowly from syphilis-- even after penicillin was shown to cure the disease-- in order to study the disease's progression.

The ethics committee at UVA that would oversee Bennett's work is called the Human Investigation Committee. It's a 22-member board composed of doctors, nurses, and non-medical community members appointed by the University. Members serve three-year terms.

Bennett says it took 11 months and three revisions for the Committee to approve his initial "protocol."

After two months-- during which he tested "huge doses" on mice with no ill effects-- Bennett was ready to give the drug to people.

What risk?

Gentry says the timing-- and location-- of the study seemed "magical."

"This study happened at this time for a reason," she recalls thinking after meeting Bennett at UVA and again after hearing him speak at an ALS Association meeting in Richmond.

Bennett's disclosure that as the drug's "inventor" he might profit from its eventual sale didn't dampen his research volunteers' enthusiasm-- a friend of one even donated $40,000 to help Bennett fund the study. And they brushed off Bennett's warning that any new untested drug could carry serious risks.

"For a person with a terminal illness, risk is not the same as risk applied to a healthy person," explains 53-year-old Norfolk resident Bob Echols, who was diagnosed with ALS in 2003. "In a way, you're kind of beyond risk," says Echols. "If you have ALS, you're going to die, period."

While Gentry says she felt new hope for herself, Echols says the same wasn't true for him: when he was diagnosed with ALS, doctors also discovered he had a second fatal neurological disorder, "Cadasil," that would not likely be improved by the new drug.

Even so, he signed up.

"It made me feel I was doing something positive for a lot of other people I knew," he says.

ALS Association spokeswoman Sarah Stein helped recruit subjects for Bennett's study, but she had little hope that this drug would succeed where so many others had failed. "I lose 50 percent of my patients within a year after meeting them," she explains. "Watching their decline is heartbreaking."

The disease can strike at any age-- and can affect any part of the body. The most common first symptom is weakness in an arm or leg, but some people suffer "bulbar" onset, in which they first lose the ability to speak and swallow. But no matter where it begins, the disease progresses relentlessly. Typically, within two years, it robs its victim of all physical function.

The final stage of the disease is a living nightmare.

"It's called 'locked in,'" says Stein. The patient can no longer walk, talk, eat, breathe, even blink their eyes. Cognitive function, however, is unaffected.

Some ALS sufferers-- like famed physicist Stephen Hawking-- choose to remain on a ventilator. Like Hawking, whose ALS has progressed unusually slowly, communication depends on high-tech gadgets-- such as computer keyboards guided by eye movement.

Before they've deteriorated to that extent, most ALS patients tell their families when they want to be taken off life support. "They come to an agreement," says Stein. "'This is how far I'll go.'"

At that point, doctors administer a large dose of morphine to render the patient unconscious. Then the ventilator is turned off.

It's impossible to describe Gentry's horror at this fate. Just two years ago, she was hoisting beams and power tools to renovate her Western Albemarle home. Now she can't lift a fork.

"I just can't believe this is happening to me," she whispers.

Unexpected results

Gentry had been taking Bennett's drug for a month when she noticed something unusual.

"All of a sudden I could move my left hand," she says. Richmond resident Bev Nicola, who was diagnosed with ALS two years ago at age 63, also noticed some exciting changes after she began taking pramipexole.

"I could get up unaided, could walk upstairs, didn't have to use a walker," she says, using a voice synthesizer that translates typed text into sound. But her 10-year-old grandson was especially thrilled with one other change. "I could say a couple of words clearly," she says-- something she had not been able to do since losing the ability to speak several months earlier.

Bennett hadn't expected to see results during Phase I of his study-- in fact, the first phase of any drug trial is designed only to look for side effects.

In addition, he believed that a larger dose of the drug-- perhaps three times the amount his subjects were taking-- would be required before any results would be noted.

But after nearly half of his study volunteers offered what he calls "little positive anecdotes," he approached the Committee and asked for another eight weeks.

That, he says, is "when the sh** hit the fan."

Safety first?

In late November, UVA's Human Investigation Committee turned down Bennett's request for an extension.

"The committee had a lot of concerns about a lack of animal safety information," says chairwoman Dr. Karen Schwenzer, an anesthesiologist. "More extensive animal studies are usually done before the drug reaches people. It's absolutely usual practice."

Bennett says he and the Committee differed on study design.

The Committee had approved Bennett for a Phase I study, in which a drug is tested only for safety-- not for any positive medical results he might observe.

A frustrated Bennett says the traditional drug study model "hasn't worked for ALS," and he had hoped to implement a "futility model" used during the early days of HIV/AIDS drug research. In such a model, researchers look simultaneously for side effects and medicinal effects. Bennett believes this allows for more rapid scientific advance.

Under the traditional model for which his study was approved, however, studying results is reserved for Phases II and III. Schwenzer explains that in those later phases, an investigational drug is tested against an existing treatment or a placebo in increasingly large groups of people. Once a drug has successfully completed Phase III testing and received FDA approval, it can be marketed.

The Committee, Schwenzer says, had no choice but to reject Bennett's request.

"Though it's very exciting to think that there's a drug out there that may help those with ALS," she says, "the paramount mission of the Committee is to protect the safety of the research volunteers."

Patients with a terminal illness are often "willing to try anything," she says. "They're vulnerable." And because of that, she says, "We want to make sure each study is done properly." Thinking long term, she explains, is crucial.

"Without adequate study design," says Schwenzer, "the future of the treatment of this disease won't be there. Good research design is what's going to help these people."

Gentry says she understands the need for solid science. As a nurse at UVA, she helped conduct several research studies. But what she doesn't understand is how the Committee can claim safety as an issue when no subjects showed signs of complications.

"Why not continue and monitor for safety?" she asks.

Like Echols, she says, safety and risk for the terminally ill are very different issues than for healthy people.

"So what if the drug kills me," she says, "the disease is going to anyway. If we can learn from the drug, then at least my life has some impact in its last few years."

UVA law school professor and ethicist Richard Bonnie says he believes members of the Committee are in a difficult situation.

"It's clear why Dr. Bennett is agonizing about this," says Bonnie, "and I'm sure that from an ethical standpoint, the Committee must be too."

However, the Committee, he says, is charged by the University with holding all human studies to the same set of standards.

"They have their job to do," he says, "and they're trying to do it."

Bev Nicola and her husband, Eli, aren't buying that explanation-- especially since her condition has worsened since she stopped taking the drug in late November.

"She's gone backwards," says Eli.

Gentry believes that the Committee based its decision on something other than medicine.

"My gut feeling," says Gentry, citing recent class action suits against the drugs Vioxx and Celebrex, "is that because UVA is the patenting agent on this drug, they're afraid they'll be liable down the road."

Nicola also questions the Committee's decision and says it's hard to know what to think when the Committee hasn't specifically answered letters that she and Gentry have sent.

"I don't think it's science or medicine in the way," she says. "I have to think it's some kind of turf control."

Schwenzer denies that legal implications played any role in the decision.

But it is clear that fall-out from a drug-study-gone-wrong can be serious. The 2001 death of a healthy woman participating in a Johns Hopkins asthma study sent ripples through the scientific research community. Many of Johns Hopkins' studies were affected, says Bennett, and the death damaged that university's reputation.

The ALS Association's Stein doesn't comment on any legal component of the Committee's decision, but she sees serious ethical problems in halting a drug study after the people taking it have begun to believe it may help.

"These people are dying," exclaims Stein. "I want to know how the Committee can allow it to go to human trial and then say there wasn't enough animal testing."

She believes the drug was groundbreaking. "It protected the nerves from further damage," she insists, "and regrew neural pathways."

Schwenzer points out that there's another possibility for the improvements: the "placebo effect." In many studies, patients who simply believe they are receiving a valuable new drug show genuine signs of improvement. In some studies, Schwenzer says, the placebo effect can be found in 30 percent of subjects.

With her nursing background, Gentry says she's familiar with the placebo effect-- and doesn't believe it affected Bennett's study.

"With this drug, we were never told it was going to do anything for us," she says. "In fact, Dr. Bennett told us, 'Don't expect anything." Plus, she says, "None of us knew about the other people's positive effects until the study was stopped. That can't be a mind issue, either."

Bev and Eli Nicola say it was simply too soon to know whether her improvements resulted from the placebo effect. Refusing to extend the study-- and taking away their hope-- was "inhumane," says Bev.

"I don't know if they really understand what's been done to people," says Eli. "It's almost criminal."

New hope

While Bennett's patients were writing letters to the Committee pleading that it reconsider, Bennett went looking for other ways to get the drug to his patients. His best bet: FDA approval for a "treatment use," known less formally as "compassionate use."

In situations where patients have serious or life-threatening conditions for which there is no effective treatment, the FDA can expedite approval for experimental drugs. Such use is not a drug study per se, though Bennett would be required to keep detailed records of any side effects. It's a system designed to provide patients who otherwise have no hope with another opportunity.

Gentry says she feels certain that Bennett won't rest until he's explored every option.

"He's from the old school, where patients come first," she says. "He's so caring, so compassionate."

Ethicist Bonnie says Bennett's decision to go to the FDA is "the right approach."

At press time, Bennett had received approval from the FDA to resume administering the drug to ALS patients. Now it's back before the Committee, which considered his request on Tuesday, February 22. If he gets approval, Bennett says he has enough money left from grants and the friend's $40,000 gift to fund treatment for six months. After that, he'll need more money.

"I hope he's successful," says Bonnie.

Schwenzer isn't making promises. "I can't predict what the Committee will decide," she explains. No final decision is likely for several weeks.

For the subjects of Bennett's study, there is little to do but wait.

"They have my life in their hands," says Gentry. "And I'm not the only one."

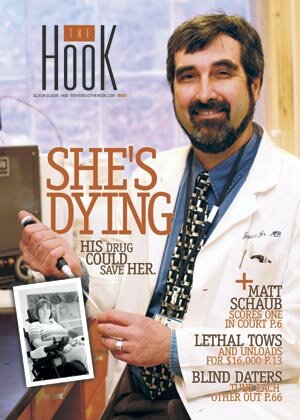

Two years ago, Mary Jane Gentry enjoyed swimming and boating. Now, she lives in a nursing home and requires round-the-clock care.

Bev Nicola named her voice synthesizer "Olga," proof that her sense of humor remains unscathed.

Bev and Eli Nicola were high school sweethearts. Nearly 50 years later, he cares for her as her condition deteriorates. "Without help from friends and our church," he says, "this disease would knock you flat."

"The paramount mission of the Committee is to protect the safety of the research volunteers," says Dr. Karen Schwenzer, chair of the Human Investigative Committee at UVA.

"This has been the most inspirational thing I've ever done," says Dr. James Bennett of his ALS drug study. "These are people who have shown me courage, resolve, patience that I didn't think was possible."

"If we can learn from the drug," says Gentry, "then at least my life has some impact in its last few years."

#

>> Back to The HooK front page

|