>> Back to The HooK front page

COVER- This mold house: Family devastated by spore war

Published March 31, 2005, in issue 0413 of The Hook

BY LISA PROVENCE

After 12 years of renting, Larry Butler and his wife, Judit Szaloki, were finally ready to make the leap into home ownership. They found a house they liked, arranged financing, and sealed the deal, thinking their dream had come true.

Their euphoria was short-lived. On a visit two days after the closing, they discovered the house was infested with mold. Two of their daughters have asthma, and one ended up in the emergency room.

The family now faces financial ruin as they struggle to cover rent on their old house, the $1,600/month mortgage on their new house-- and a clean-up bill estimated at $30,000.

"This is our first house," says Butler, "and it's a nightmare."

Just another "dump"

Three years ago, Butler opened a magic shop. He was struggling to cover the rent on the Ivy Square store, and the family was dependent on Szaloki's income from a day-care business she operated in their rented house near Albemarle High School. "My wife's business," he says, "was going to pay the mortgage."

They had been looking for an affordable place to buy for the past six years. In the increasingly heated Charlottesville market, they found houses sold before they could even make an offer. "Every year houses go up $10,000," he says. "I felt this was my last chance."

Built in 1960, the 2,200-square-foot brick ranch house off Angus Road appealed to the Butlers. It has four bedrooms and a ground floor family room and kitchen that would be ideal for Judit's day-care center. They paid $246,000 for the house at 2207 Wayne Avenue.

"It's no mansion," says Larry. "It's just another over-priced dump here in Charlottesville, the number-one city. This place should sell for no more than $150,000."

The deal on the house closed February 10. Then, two days later, "We found out how bad it was," he says.

A mildewed smell greeted the Butlers when they stepped into the house. They say they'd been told it was a new polyurethane finish on the floor. When the smell persisted, they thought the downstairs carpet was the culprit, and Larry set about ripping it up.

Then he went into the downstairs kitchen and opened one of the cabinets. "The mold," he says, "was an inch thick."

So thick a smell

White, feathery mold-- the Butlers originally thought it was a huge spider web-- is nestled inside the cabinets. Black and orange mold adorns a board behind a cabinet Butler pulled out. He demonstrates for a reporter how easily a rotted stud breaks off.

Black mold fills a hole Butler has cut in the sheetrock in a closet. The basement rafters are covered in green mold. "It's everywhere," he groans.

By Valentine's Day, the couple was in despair. A waterproofing company wanted $20,000 to take care of a flooding problem-- although the Butlers allege initially they were told the house had never flooded.

"They brought it down to $17,000, then $14,000, and said I had to sign a contract that day with a down payment of $1,400," Larry says. He didn't have $14,000-- or even $1,400.

More puzzling, say the Butlers, is that the sellers claimed the flooding problem had been fixed four years before-- but then refused to provide documentation on the repairs.

He contacted lawyers. Their response: "The inspector told you there was mold," he says. "Well, you knew. And the sellers sold it 'as is.'"

The Butlers concede that the pre-sale home inspection they ordered indicated the presence of mold.

"We didn't know the severity of it," says Larry Butler. "We were led to believe by our realtor that we could wipe it down with Clorox and fix it ourselves."

Butler feels betrayed, especially by his real estate agent. "She was our buyer's agent and supposed to protect us," he says. Now, says Butler, she denies making the Clorox suggestion.

The agent, Sirlei Kaiser-Ramirez, stopped by the house as Butler was showing the mold to a reporter February 16 and asked if he had called the health department.

"I'm trying to help," she says. "I'm really sorry this happened." Later, Kaiser-Ramirez refers a phone call from The Hook to Pat Jensen, her broker at Real Estate III.

"When the Butlers first looked at the house, it was pointed out that there was some mold/mildew in the basement kitchen cabinet," Jensen says in an email. "The home inspector noted that there was evidence of moisture/mold or mildew. The Butlers' Real Estate III agent gave the buyers a coupon from a waterproofing company that specialized in mold/mildew/waterproofing and suggested they call an expert to find out if the problem was serious."

Larry Butler scoffs at the 10 percent-off coupon. "It was a Val-Pak coupon. Nowhere on it does it state mold remediation," he says.

"The buyers had several opportunities to choose not to go through with the transaction," continues Jensen. "They called the people from the coupon the day after closing and found out there was a serious issue. Real Estate III is trying to explore options with the buyer in order to effectively address this unfortunate situation."

Jensen, a former president of the Charlottesville Area Association of Realtors, says she has no knowledge that the Butlers were told the mildewy smell came from polyurethane on the floor.

And, she notes that it was Montague, Miller-- not her company-- that represented the seller. The listing agent was Shann Whited.

"I have been told by my broker not to comment," Whited says. The sellers, Steve and Betty Dudley, did not respond to several phone messages.

Odessa Snow has lived on Wayne Avenue for 34 years, and she knew Steve Dudley's parents. "I haven't been in the house since 12 years [ago] when his parents lived there," she says. "His parents had the basement rented, so I don't think there was a problem then."

However, Snow reports that about two years ago, a heavy rain flooded the house. The tenant at that time moved out, and she believes the house had been empty since the flood. Snow doesn't understand how the house could be sold in such a condition.

"I feel so sorry for [Larry Butler] that he paid so much for it and has to do all this," she says.

"I feel like a big idiot," says Butler. "I put my trust in someone. I can't move my family in. It's not right. My family deserves better than this."

Despair city

"I have seven people, including me, at home with symptoms such as nose bleeds, runny nose, burning eyes, coughs, congestion, wheezing, chest tightness, shortness of breath, sore throats, tender lymph nodes," says Judit Szaloki.

It's less than a week after signing the papers for her new house, and she's just back from spending the evening in the emergency room with her oldest daughter, Emese, whose asthma worsened after being in the Wayne Avenue house for a couple of hours.

"You tell me if you would let your children suffer like this," demands Szaloki. "That house should nave never been sold 'as is.' It has to be a health code violation."

Actually, the health department doesn't monitor mold. "We have not yet gotten involved in the mold issue," says Ray Crewz, epidemiologist for the Thomas Jefferson Health District. "There are no real standards."

Nor does mold affect everyone the same way. "The majority of people don't even know they're around mold unless it's really high levels," says Crewz.

Mold and other indoor air quality issues are such new and controversial topics that few state or local codes address them at all.

In what's considered the wake-up-call case on the dangers of mold, Melinda Ballard v. Farmers Insurance Group, a Texas jury in 2001 awarded a family $32.1 million after thick black mold in their Austin mansion allegedly caused various health ailments. The award was later reduced to $4 million.

Other prominent victims of mold include television personality Ed McMahon, who won a $7 million settlement after mold caused by a burst pipe allegedly killed his dog and sickened his family. And environmental crusader Erin Brockovich sued a builder over mold in the L.A.-area house she bought with the money she earned for helping expose environmental hazards caused by Pacific Gas & Electric.

The Butlers, however, are neither rich nor famous. Faced with estimates of thousands of dollars to remove the mold, Larry Butler decided to do it himself. With the help of friends, he ripped out cabinets, carpet, and ceilings. And in doing so, he may have exacerbated the problem.

"He's done a lot of demolition," says Joel Loving at Environmental Health Consultants, a firm that performed on-site testing. "He scattered mold spores everywhere. That made things much worse."

In desperation, the Butlers decided to close off the basement and move in upstairs. But that plan was abandoned when Loving's test results came back on March 14 revealing high levels of aspergillus and stachybotrys-- even upstairs.

Stachybotrys chartarum is a thick black mold that has made headlines for emitting allegedly dangerous toxins. Like other molds, it can grow unabated when water gets into a building.

"The air quality is poor," says Loving. "Under the current status, I would not advise anyone with young children to be in there."

Disputed danger

The Ballard family of Austin and others alleged lung damage and brain damage in their suit against Farmers Insurance. And a 1999 Mayo Clinic study blamed chronic sinusitis, a condition that affects about 37 million people in the United States, on an immune response to mold.

But that's not to say that any mold-- even stachybotrys-- has entered the medical hall of shame. Critics charge that before mold makes its way into the pantheon of trial lawyer dreams-- behind asbestos, Ford Pintos, and Dalkon shields-- the science has some catching up to do.

"There's no definition of high levels," UVA's allergy expert, Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills, told The Hook in 2003. "When you try to pin us down in the scientific community, we all turn to jelly."

Indeed, a Q&A on the Centers for Disease Control website suggests that the danger of molds to the average citizen may be overblown.

"There is always a little mold everywhere," says the CDC. However, while the CDC notes that no causal link has been found between mold and some of the frightening medical conditions blamed on it, the site does say that those with asthma or compromised immune systems may be at risk of complications.

There are no standards for safe levels of mold. For aspergillus, Loving explains, ideally the spore count would be lower inside than outside, where it's found naturally.

"This was extreme," says Loving of the contamination in the Butler house. If it's twice or even three times the load found outside, that's one thing, he says. But "This is 10 to 20 times worse."

As for stachybotrys, anything over three counts of spores per cubic meter is considered "legitimate contamination," says Loving. The raw count found at 2207 Wayne Avenue: seven.

Judit Szaloki is sick again. "I never get sick, but now I am unable to do very much," she says.

The family had moved some of their belongings into the upstairs of the house. "Now our stuff is contaminated," says Larry Butler. "We bought a $246,000 house, and we can't live in it."

Remediation

Air-quality consultant Loving thinks the house is salvageable: "You don't have to plow this house under. It could be fixed," he says. He estimates the cost at between $10,000 and $20,000 and advises, "They should have professionals do it."

That's little consolation to the tapped-out Butlers.

While doing the air quality test, Loving noticed water damage two feet up the walls of the basement. "It's pretty obvious from the mold growth that this house was flooded. And it was left flooded to have mold that far up," he says.

Loving wonders one thing: "Does 'as is' mean 'I'll buy it, I don't care about the secrets you're keeping'?"

"Virginia basically is a caveat emptor state," says real estate attorney Bill Tucker. "We caution every buyer."

The Butlers, like a majority of homebuyers in Virginia, bought their house "as is." That means the seller makes no warranty about the condition of the house.

Sellers can choose "disclosure" and answer questions on "about 30 items in the house and what you know about them," says Tucker. The other option is the "disclaimer"-- "as is"-- and, not surprisingly, Tucker says, attorneys advise sellers to use that option.

"'As is' allows the buyer to do an inspection and maybe elect not to buy it," Tucker says. When the inspector sees evidence of mold, "That should be a red flag to the buyer to say 'Wait a minute.'"

Legally, that makes it more difficult for the Butlers. "He knew of the risk, and he still accepted it," says Tucker. "It's hard to say it's fraud if they had some notice of it."

Butler contends that while he had notice of mold, mildew, and even asbestos, he didn't know the extent because he "couldn't take a hammer and knock the wall out because I didn't own it."

So far, few states have followed the lead of California, which in 2001 passed the Toxic Mold Disclosure Act, which requires sellers to disclose any potentially dangerous mold problem.

But there are some protections-- even in caveat emptor Virginia.

"The law requires disclosure of adverse material facts about the property," says Dave Philips, the CEO of the Charlottesville Area Association of Realtors. If they knew, says Phillips, "realtors would have to disclose an issue, such as if the roof leaked or there's mold in the house."

So while painting and recarpeting are common methods of primping a house for sale, some sprucing up could be illegal. After Larry Butler found a fresh coat of paint in the mold-ridden basement and discovered the carpet he ripped out was brand new, his suspicions intensified. Hook calls to the previous owners were not returned.

"If someone intentionally is covering up a defect in a home with the intent of hiding it from a potential buyer," Phillips says, "it can be considered fraud."

City Councilor Blake Caravati has been in the construction business for 28 years, and he was the person hired to perform the Wayne Avenue home inspection.

"I'm not Superman," says Caravati. "I can't see through walls. The severity of the mold wasn't revealed until [Butler] took the cabinets and walls out."

Were the Butlers naive to continue with the purchase despite Caravati's report detailing fungus, mildew growth, and high humidity in the house?

"When someone as serious as I am puts it in writing, you should ask questions," says Caravati.

"I feel like everyone told us this was no big deal," says Judit Szaloki.

"There are remedies," says Jerry Tomlin, Charlottesville's building code official. "We have a program for first-time buyers who have emergency-type repairs. They can get low-interest loans." Tomlin calls it "a little boost, just like we did with Chrysler," referring the famous early-'80s government loan guarantees for the then-struggling automaker.

Tomlin also says the city can help the Butlers find someone to do the remediation. "I don't think it's worth tearing down a house," he says.

"I don't know what to do," says Larry Butler. His homeowner's insurance doesn't cover mold. "I'm at the end of my rope. I really have never been so disgusted or so stressed out-- and that's after 10 years in the Marines."

He's down to his last $1,000 and is wondering whether to pay the mortgage on the house he can't inhabit or spend it on the rent on his store. "I may have to file bankruptcy," he says. "I'm angry with myself for letting this happen to my family."

Butler thinks there's something wrong with the law that makes it okay to sell a house that's uninhabitable. "We still feel cheated and misled," he says. "It's just wrong. It seems like they should make the seller buy it back."

Although in 2001, a permit was issued to run a day care at that address, Judit Szaloki can't fathom the idea of moving her day care business into a house with mold, and she thinks the house should be condemned.

"This is something that involves lives," she says.

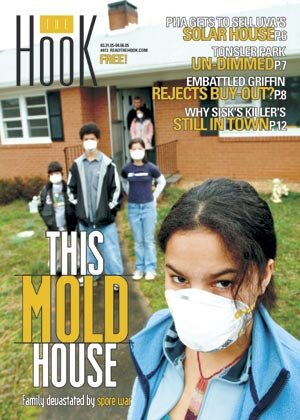

Larry Butler wanted a nice home for his family. Instead he's got a mortgage, no place to live and may be facing bankruptcy.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Larry Butler and Judit Szaloki's dream house has turned into a mold-infested nightmare.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Sixteen- year-old Emese Szaloki spent the night in the emergency room after a couple of hours in the family's new house. Erik, 14, Eryka, 12, and Bence, 8, thought they'd be living in their new house by now.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Larry Butler believes the rotted studs in the basement are evidence of major water damage-- that wasn't visible until he started ripping out cabinets and walls.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#

>> Back to The HooK front page

|