COVER- Solar coaster: The ups and downs of sun energy

Published May 12, 2005 in issue 0419 of The Hook

BY COURTENEY STUART

If you wore bell-bottom pants and platform shoes in the 1970s, you were groovy. If you placed a few solar panels atop your home or business, your cool factor went through the roof-- literally.

Though solar panel technology had been commonly used in the early twentieth century and was especially popular during World War II, by the early 1980s, solar panels-- once prohibitively expensive-- had become accessible to the middle class thanks to significant federal tax credits enacted by the Carter administration.

But 20 years after Ronald Reagan removed those credits, solar-- like a onetime disco diva-- has lost its cachet. Can it make a Cher-like comeback in Charlottesville, or is it doomed to loll in obscurity like the Captain and Tennille?

****

When Roger Voisinet and David Watkins started Virginia Solar Contracting Services in 1980, the two young engineers figured they'd stay busy. But they had no idea just how busy.

"Within a few months we had eight employees," recalls Voisinet, 55, now an area real estate agent and coach of the UVA ice hockey team. Within five years, the company was flying high with annual sales around a million dollars.

The reason for that rapid growth? President Jimmy Carter's 40 percent federal tax credit, which meant that a family who purchased a typical $5,000 solar system to heat water could recoup $2,000 at tax time. When the Commonwealth of Virginia added an additional 20 percent credit, that family's return climbed to $3,000. Counting in the typical 65-70 percent savings on energy used for hot water, Voisinet says, the system usually paid for itself within five years.

A typical residential solar installation includes several rooftop panels set at a particular angle to maximize their sun exposure. Those panels collect the sun's energy and heat water-- or in some cases antifreeze-- which in turn flows through copper pipes and transmits the heat to water in a tank. In some cases, the heated water flows through copper pipes in a concrete floor, providing radiant heat.

But while residential installations were very common in solar's halcyon days, commercial entities may have seen the greatest returns on their solar investments in the years since, despite the fact that they were only eligible for a 10 percent federal tax credit.

"I think we're the only ones smart enough to do that in the world," says Lloyd Wood, owner of the solar-powered Jiffy Clean Car Wash on Route 29. "Knowing that energy prices were going up sky high, it just made sense to let Mother Nature help a little bit."

It's been 20 years since Wood built his solar carwash, and he says he can't calculate the amount of money he's saved. But he's sure of one thing: his initial $30,000 investment has long since paid off.

At Jiffy, the solar panels heat the water from the temperature at which it arrives from the reservoir-- between 55 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit-- to approximately 105 degrees. Natural gas boost the water the final 15 degrees to washing temperature of 120.

"Theoretically, that's a savings of 25 to 50 percent a month," says Wood, who claims he "would have done it even without the [tax] credit."

Wood's not the only one thrilled with his commercial solar investment.

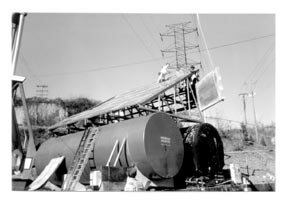

Over on River Road near Pantops, solar panels have been heating massive tanks of asphalt for more than 20 years. And though the sleek glass panels seem somewhat out of place in an industrial lot filled with rusty metal, they've proven they're tougher than they look.

"There's no telling how much money it's saved the company," says Jerry Baber, plant superintendent for paving biz S.L. Williamson Co. Inc..

The solar panels heat two 18,000-gallon tanks that keep the asphalt as slurry. And while the tanks' insulation has deteriorated over the last two decades, the system itself has required "practically no maintenance," says Baber.

Not every 1980s solar system is still going strong. Consider the English Inn on Emmet Street. Originally equipped with solar panels to heat the indoor pool, there's now nary a sign of them.

While Fred Chason, president of Wytestone Company, which owns the English Inn as well as several inns in Fredericksburg, did not return the Hook's call by press time, a front desk clerk says today's toasty pool owes nothing to solar heat since the panels stopped working years ago and have been removed.

No matter how lavish the property or the solar installation, Voisinet explains, the complicated technology up on the roof may require special care, and the original owner may not be around to offer maintenance tips.

In the case of the English Inn, the hotel was developed in 1983 at the height of the solar boom. Ten years later, after a recession rocked the lodging industry, the property changed hands in a foreclosure auction.

Voisinet calls such a site that has lost the "parents" of its sun-based system a "solar orphan." For Voisinet, touring solar projects around Charlottesville is a trip down memory lane. But unfortunately for him, that lane is also a dead end.

In 1986, the federal tax credit was revoked, and the effect on solar was immediate and profound.

"Sales dropped to almost nothing overnight," says Voisinet, who with Watkins "hung on for another year," hoping the situation would improve.

Watkins was-- and remains-- disgusted with the way the Reagan administration dealt with the solar industry.

"The wisdom of the Jimmy Carter approach was to give solar a kick start," says Watkins. "The idiocy of the Reagan approach was to cut it off immediately" rather than phase it out over several years.

From 1985 to 1986, Virginia Solar's sales went from close to $1,000,000 to between $50,000 and $60,000, says Watkins, who points out that small companies weren't the only ones who suffered. Reynolds Metals, a Richmond-based company that had been a leading producer of solar equipment nationally, was forced to ditch its solar component.

"They faced the same kind of thing," says Watkins. "Sales dropped 90 percent."

In 1986, Voisinet and Watkins folded their company under better circumstances than many other small solar contractors. "We didn't go broke, but we paid our debts and went home," recalls Watkins. "The people who were experienced and could have maintained [the systems] were dispersed."

Since then, the big rage in solar has been passive solar-- the notion of designing buildings oriented to collect sunlight in the winter and deflect it in the summer. For existing structures, green gurus have been touting the idea of planting deciduous trees on the south and southwest sides of buildings-- to provide summer shade and winter light.

Today, Voisinet foresees a revival of more technical solar devices thanks in part to the rising tide of energy prices. He notes that there's still a 10 percent federal tax credit for businesses, and many states-- including Virginia-- are considering additional credits.

Consumers are well-known to embrace green technologies only to reject them when actually asked to pay. Watkins mentions the Toyota Prius. It's not the first hybrid car, but it's the first to become so popular that there's now a waitlist in many American cities.

That demand, Watkins says, is thanks to the Prius' relatively low cost, as little as $21,000. But because solar requires an upfront financial investment significantly larger than a traditional furnace or hot water heater, many consumers have been reluctant to embrace solar building or renovation plans. That could change, however, if energy costs continue to skyrocket.

But before solar can take center stage again, Watkins says the costs of the installations need to come down or traditional energy prices need to go up even further.

"Let oil stay at $50-80 a barrel, and it will work its way through," he says. "It's the touchstone for all other energy."

One massive energy company appears to be leading the return to solar. BP Solar, a subsidiary of BP Global, is currently the largest provider of photovoltaic panels in the world. (Photovoltaic panels convert sunlight into electricity rather than heating water directly.)

Some local businesses are getting back on the solar bandwagon as well.

Local health club ACAC uses solar to heat the outdoor pools at its Adventure Central location, and the club plans to include a rooftop solar-heated pool in its new downtown club under construction in the former Ivy Industries building.

The savings in heat costs for the Adventure Central pools is in the "tens of thousands," according to ACAC COO Grant Gamble, who adds that the $50,000 system put in place three years ago paid for itself by last year.

Watkins hopes it's a sign that solar can make a comeback.

"It's a technology that we ought not to give up on," he says.

THEN: Built for Southern Railway, the depota $60,000 building with $80,000 in solar equipment on West Main Street-- could have done all its train switching with no outside power.

PHOTO BY ROGER VOISINET

NOW: Now owned by Norfolk Southern Railway Company, the depot on West Main Street isn't used for anything, according to Norfolk spokesman Robin Chapman .

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The Jiffy Clean Car Wash is the only solar car wash in Charlottesville. The Jiffy Clean Car Wash is the only solar car wash in Charlottesville.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

This Locust Avenue house is equipped with solar panels to heat hot water.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Solar panels heat ACAC's outdoor pools to approximately 85 degrees.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

THEN: A Polaroid from the early '80s shows the English Inn when its solar panels were in working order.

PHOTO BY ROGER VOISINET

NOW: The English Inn's solar panels are now gone, and Roger Voisinet says the Inn is a "solar orphan," a term that describes solar technology that's abandoned at a particular site.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

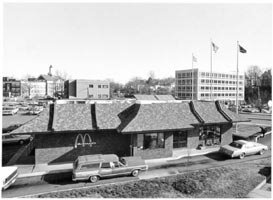

THEN: Solar panels provided hot water at the McDonald's on Ridge McIntire in the early 1980s.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

NOW: Once crowned by solar panels, the McDonald's roof is now bare.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

THEN: Solar panels heat massive tanks of asphalt at S.L. Williamson on River Road.

PHOTO BY ROGER VOISINET

NOW: The tank insulation crumbles, but the solar panels keep heating that asphalt slurry.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Virginia Solar Contractors co-founder Roger Voisinet.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#

|