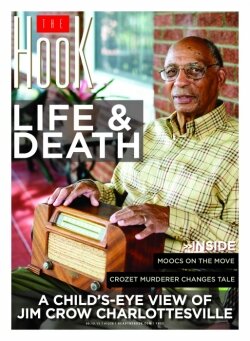

Life and death: A child's-eye view of Jim Crow Charlottesville

-

eugene williamsjen fariello

eugene williamsjen fariello -

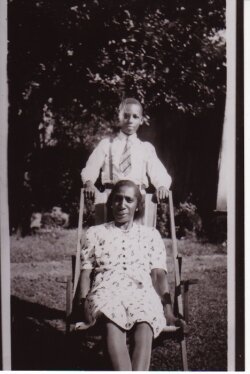

Young Eugene Williams stands behind his mother, Seppie.Courtesy Eugene Williams

Young Eugene Williams stands behind his mother, Seppie.Courtesy Eugene Williams -

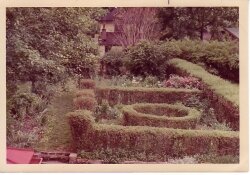

Peachie created this small garden room, or parterre, behind the house on Dice Street, and tended it carefully until his death.Courtesy Eugene Williams

Peachie created this small garden room, or parterre, behind the house on Dice Street, and tended it carefully until his death.Courtesy Eugene Williams -

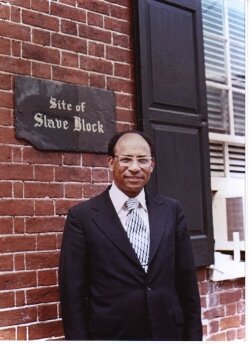

This picture of 0 Court Square was taken in 1978. At some point the slate plaque was removed, although plaques on nearby buildings remained. Mary Joy Scala, ACIP Preservation and Design Planner for the City, isn't sure why it was removed, but it will be replaced "soon" with a marker in the sidewalk.Courtesy Eugene Williams

This picture of 0 Court Square was taken in 1978. At some point the slate plaque was removed, although plaques on nearby buildings remained. Mary Joy Scala, ACIP Preservation and Design Planner for the City, isn't sure why it was removed, but it will be replaced "soon" with a marker in the sidewalk.Courtesy Eugene Williams -

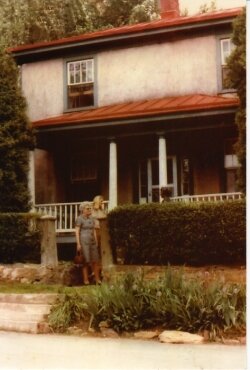

The house at 138 Dice Street. Seppie is behind the hedge on the right. The women, who are not identified, were among her employers.Courtesy Eugene Williams

The house at 138 Dice Street. Seppie is behind the hedge on the right. The women, who are not identified, were among her employers.Courtesy Eugene Williams -

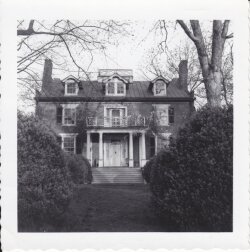

This house, at 301 Ridge Street, was owned by Al and Bertie Yancey. The property is now the site of Noland Bath and Idea Center.Courtesy Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society

This house, at 301 Ridge Street, was owned by Al and Bertie Yancey. The property is now the site of Noland Bath and Idea Center.Courtesy Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society -

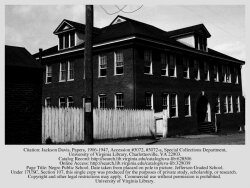

Jefferson Elementary School, 1921:The school was built in 1894 and destroyed in 1959.University of Virginia Library

Jefferson Elementary School, 1921:The school was built in 1894 and destroyed in 1959.University of Virginia Library -

The Inge family, which included five children, lived above the grocery. Booker T. Washington stayed there once, during the time when blacks could not rent hotel rooms. It is now the site of West Main Restaurant.Courtesy Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society

The Inge family, which included five children, lived above the grocery. Booker T. Washington stayed there once, during the time when blacks could not rent hotel rooms. It is now the site of West Main Restaurant.Courtesy Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society -

Williams and his brother Albert gave this radio to their mother after their father's death in late 1937.Jen Fariello

Williams and his brother Albert gave this radio to their mother after their father's death in late 1937.Jen Fariello -

Eugene and Lorraine bought their house at 620 Ridge Street in 1956. To pay the mortgage, they lived upstairs with their daughters and rented the downstairs.Jen Fariello

Eugene and Lorraine bought their house at 620 Ridge Street in 1956. To pay the mortgage, they lived upstairs with their daughters and rented the downstairs.Jen Fariello

The headlines in the Daily Progress that September described a world that was as distant as the moon to the boys who slept and woke on Dice Street. “France Prepares for War Threats,” one read; in Germany, Hitler joined “50,000 disciplined youths” at the annual Nuremberg Rally and watched as hundreds of artillery units and tanks streamed past the reviewing stand and the Hindenburg hovered overhead.

The 1936 presidential campaign was in full swing, and Amelia Earhart was “nearly sold” on the idea of flying around the world. When it became known that Wallis Simpson was King Edward VIII’s guest at Balmoral Castle in Scotland, Warrrenton socialites buzzed with memories of the year she had lived among them while waiting to be divorced from her first husband. And in Greenwood, Lady Astor—the former Nancy Langhorne—was in residence at Mirador, her family home.

The Progress rarely had news about anything that concerned the boys on Dice Street, but September 1 was an exception: “The white schools of Albemarle County opened this morning for the 1936-37 session,” the then-afternoon paper announced, and went on to note that “the colored schools will open tomorrow.”

There were two Charlottesvilles then, sharply divided by customs and laws so ingrained that “the colored schools will open tomorrow” could be just another bit of local news in the Progress. It was as if the boys who lived on Dice Street, Eugene and Albert Williams, moved through a kind of parallel universe: They went to school, but to one that had almost nothing in common with Venable or McGuffey or the other white schools the Progress wrote about and photographed and touted. And that was only one aspect of the world they traveled through in plain sight but inhabited, seemingly, just below the surface.

Seventy-seven years have gone by. The colored school is gone. But Eugene remembers, and in a soft voice that rises in outrage when a memory is too raw, he tells his story. He’s on Dice Street again, and he’s nine years old, and it’s morning.

* * *

Their parents always left early—their mother to work in other houses and their father to tend other gardens—so the boys were used to waking to a silent house. Their morning routine was simple: They dressed in knickerbockers and shirts and the shoes their mother bought on credit at the Victory Shoe Store on West Main Street, and one of them emptied the chamber pot, carrying it to the outhouse in the far corner of the back yard and then returning it to the room they shared.

In the kitchen, they filled a basin with water from the water bucket and washed up, then Eugene poured out cereal for himself and Albert, along with milk from their still-new electric refrigerator. Their parents had bought it from a man who went door to door in the evenings with pictures of refrigerators; it came with a meter, which they fed with quarters. Every week, the man came to open the box with his key and collect the quarters.

After breakfast they took their book bags and, stepping out on the front porch, closed the door behind them as, up and down Dice Street, children emerged from other houses. They were all headed to Jefferson Elementary School, where Eugene was in the fourth grade and Albert in second.

* * *

The trip up Ridge Street represented more than the simple turning of a corner; it meant going from a dirt street that was 30 feet wide to a paved street that was 60 feet wide. Only one family owned a car on Dice Street, and only one family, the Michies, had indoor plumbing; everyone else had an outhouse—and, for water, a pipe with a faucet that came up out of the ground in the back yard. Like several of their neighbors, the Williamses had electricity; some families still used kerosene lamps. The family also had one of only two telephones on the street— their father did day work, and wanted to ensure that the people he worked for could reach him on short notice.

The Ridge Street blocks that Eugene and Albert walked every day are occupied now by the Noland Company, the fire station, and the Salvation Army. In 1936, however, there were spacious homes on the 200 and 300 blocks that not only had all the amenities, but employed other people to keep them clean and well landscaped.

Eugene would later think of those trips up Ridge Street as an education in how the wider world saw him: Gradually, he realized that although he greeted the people he saw on their porches—and although he knew their names and what the men did for a living—to them he was largely invisible, and few returned his hello.

“Something was just embedded in me,” he says; “something just bothered me, to see that kind of living. People would sit on their porches, and you would speak to them, and because of the color of your skin, they wouldn’t even say 'hi'.”

This silent education didn’t just unfold on Ridge Street. In the summers, he and Albert would go with their father on his jobs, and in the mornings they would work alongside him. But after lunch, they’d be free to play with the owners’ children— or rather, they’d be free up to a point; for instance, they weren’t allowed inside the house. And even though they could call the white children by their first names, as soon as they came home from college for the first time, Albert and Eugene had to call them “Mr.” and “Miss.” Sometimes, Eugene remembers, they acted like they didn’t even know him—and that, he says, was “the most insulting thing of all.”

* * *

They crossed Ridge Street at the bridge over the C & O tracks, beyond which, on the right side—where Midway Manor is now—white teenagers were climbing the steps to Midway High School. On the left side, they passed the trolley-car storage shed and Mt. Zion Baptist Church. The remainder of the block ran alongside the Virginia Public Service Company—the electric company—which, in addition to providing power, owned the shed full of trolleys that, the year before, had been replaced by buses.

Ridge Street ended at the Lewis and Clark statue. In those days there was no Ridge-McIntire connector; instead, West Main Street continued in a solid row of storefronts, angling downhill through the land occupied today by the federal building and the Omni Hotel to East Main Street. West Main Street was the southern border of Vinegar Hill—20 vibrant, densely populated acres of primarily black homes and businesses roughly bordered by West Main Street, Fourth Street, and Preston Avenue.

At the statue, the boys turned left onto the 300 block of West Main Street, which was chock-a-block with businesses: Pollard’s Barber Shop, Charlottesville Motors, Inge’s corner grocery, a shoe shine, Morris Brothers sheet metal, and several others. At Inge’s Store the boys turned right onto Fourth Street and, just past Commerce Street, arrived at their destination: a dark, hulking, two-story building that faced Zion Union Baptist Church across Fourth Street and, beyond it, the heart of Vinegar Hill.

The school had been built in 1894 and taught Grades 1 through 8; behind it, the high school offered Grades 9-11. The elementary school had no playground, only a dirt yard to run around in. There was no lunchroom, either. One of the teachers would make a pot of soup every day, but only the poorest students ate it; Eugene and Albert would wait to eat until they got home. There was no auditorium, so assemblies were held in the central hallway on the bottom floor—but everyone had to stand, because there were no chairs.

* * *

Their mother, Seppie—short for Septimia—would leave home at 7am to catch the bus. She was 47 that year, and had probably been working since she was 14 or 15, which was when most black teenagers went to work. She was from Esmont, where her father had worked in the Alberene soapstone quarry, now located in Schuyler, and had done some small farming.

Seppie worked every day, with Thursday and Sunday afternoons off. Some of the families she worked for lived on Ivy Terrace—now Bollingwood—in homes where it could take half a day to polish the silver. Sometimes she worked for Ellie Keith, who had a riding academy behind her house, but more often she worked for Nannie Cole in her sleekly modern house and, across the street, UVa professor George Young and his family. For roughly 50 hours every week, she moved through the rooms and up and down the stairs of another family’s home, cleaning, cooking, ironing, washing clothes, airing woolens, storing them in deep closets for the summer, airing them again in the fall, and carrying them upstairs, prickly in the September heat.

* * *

Their father’s real name was Eugene, but everyone called him Peachie. From March through November, he worked in gardens and yards near the university; on Ivy Terrace, like Seppie, he worked for the Youngs. Seppie and Peachie refused to work for what most blacks were paid—10 or 15 cents an hour—but still made less than whites, who could command a quarter for the same work. Peachie, who had been born on Christmas Day of 1877, was 58 that year; unlike Seppie, he always walked to work.

His past was a mystery to the boys. He was much older than most boys’ fathers—50 when Eugene was born, 52 when Albert came along—and somewhat reserved. In any case, they remember no stories about his childhood, and had only met one person who might be a relative: a man who would sometimes come to the house in winter, when Peachie wasn’t working, and spend the day. Eugene remembers the man as coming from Shadwell, and grew up assuming that his father had, too.

The 1880 Richmond census offers the only clue to Peachie’s family: It lists a Henry Williams, who was a widower with six children. They ranged in age from 2 to 11, and one, Eugene, was 3 that year—the same age as Peachie. Henry had been unemployed for 12 months, and his circumstances must have verged on the desperate. Perhaps, unable to manage, he had sent the children to live with relatives, and the siblings had been scattered over wide distances; perhaps, as they grew up, they lost contact with each other.

In any case, Henry isn’t mentioned again, and the next time Peachie appears is in the 1910 Charlottesville census. He was living with his first wife, Maggie, at 331 Preston Avenue—where the County Office Building is now—and working as a cook. In 1913, they bought the house at 138 Dice Street for $450, but didn’t move in; instead, they stayed on Preston Avenue and, most likely, rented the second house for extra income.

Six years later, in 1919, Maggie died at the age of 27 and Peachie buried her in Oakwood Cemetery, in the section separated by a fence from whites. He continued to live on Preston Avenue until 1924, when, 11 years after buying it, he finally moved in to the house on Dice Street. Most likely, that was when he married Seppie and, at 47, embarked on the final stage of his life.

The white stucco house had green trim, a red metal roof, and a wide front porch. The living room was on the right side of the house, and the dining room, on the left, had stairs to the second floor and, on the wall, the party-line telephone that would sometimes ring with an offer of work and, at other times with a message to be carried to a neighbor. The spacious kitchen, which was always warm, was at the back.

The house had three bedrooms: One for Seppie and Peachie, one that would sometimes be rented to young people who had come from Esmont to look for a job, and one for the boys who would someday sleep there.

* * *

They called him a gardener, but he was much more. He built rock walls, for one thing; he had built two for the house on Dice Street, one level with the street and the other with the hedges in the front yard. On either side of the steps leading up from the sidewalk he had planted bearded iris, and, bracketing the front porch, slender, stately evergreens.

Peachie’s best creation, though, was the parterre in the back yard—a tiny garden room so striking that, almost 80 years later, a landscape designer would admire the only surviving picture and remark that “a lot of artistry” had gone into it. It extends at right angles from the Chinese privet hedge that enclosed the entire property; the hedges that form the parterre’s sides and front are shorter, with taller “columns” at the front corners and on either side of the entrance. A circular hedge, shorter still, is at the center, and along the inner walls he created a soft edging of perennials.

The rest of the back yard has been carefully designed as well, in a lush landscape of flowers and shrubs. Perhaps it was his own garden he thought about as he moved through other people’s; his own garden he designed as he worked in that world.

* * *

After school, Eugene would take the money Seppie had left on the kitchen table and go to Mr. Detamore’s on West Main Street. There was always 10 cents for a pound of hamburger, hot dogs, or baloney, and if she’d left a nickel, he’d get a loaf of bread as well. After that he was free to play marbles in the street with the other boys or to play in the open lot at the corner of Ridge and Dice (where a convenience store is located now) with white boys from Ridge Street and black boys from Dice.

Peachie got home around 5pm and made dinner for the three of them, since Seppie wouldn’t get home until 7. One of his main pleasures was reading the Progress; it was easy to spot the rare mention of blacks, because their names were always followed by “colored.” Otherwise, blacks commanded little attention. Peachie certainly would have checked the obituaries, but—except for stories about Joe Louis or Jesse Owens—he probably paid little attention to the sports page, and none at all to the gushing society page. And if his eye ever landed on Hambone’s Meditations, it would have moved away quickly.

The one-panel cartoon always ran at the bottom of the editorial page, and in it Hambone would reflect on his world and his employer—the Colonel—and the Colonel’s family. In one, for instance, Hambone stands beside a bushel of cotton and says, “Miss Lucy gittin’ atter me fuh leavin’ de hoe an’ de rake outside—but she know ain’ no nigguh gwine steal nothin’ t’ wu’k wid!!”

Two black papers, with news that would never appear in the Daily Progress, arrived every week on the bus: the Baltimore Afro-American and the Norfolk Journal and Guide. The Reverend Richard Hailstock would deliver the Afro-American to subscribers, and the Guide was sold at Inge’s Store.

* * *

The kitchen was their gathering place for meals and school work and simply being together, especially when the weather turned cold; the house didn’t have central heat, but the kitchen had a coal cooking stove. They also had a Heatrola in the living room, but it would only be turned on for church-club meetings, Thanksgiving dinner, and at Christmas. The Heatrola, which they’d bought at M.C. Thomas, resembled a piece of furniture more than a large coal stove. It wasn’t the house’s only elegant touch; the dining room had china that Seppie’s employers had given her, and in the cold months, when there was no work, Peachie would use a heavy push-broom to wax and polish the wooden floors.

In the evening, after dinner, they would wash the dishes, pouring water they had heated on the stove into a pan on the kitchen table. When it was time to wash clothes, one of the boys would fetch the tub and washboard from the coal shed in the back yard. They used the same tub to wash themselves, and once a month, Peachie would clip the boys’ hair. They had a battery radio, but it didn’t work well; whenever Joe Louis fought, they would all go down the street to the Paynes’ house to listen.

On Sundays, since so many black men and women had to work, black churches would have one service in the morning and another in the evening. Peachie and the boys would go to Ebenezer Baptist Church on Sixth Street in the morning for Sunday school and the 11am service, and then, in the evening, return with Seppie.

* * *

In November FDR beat Landon in a landslide, and by the end of the month it was too cold for Peachie to work. He turned 59 on Christmas Day, and, in March of 1937, began working again, clearing away the debris of winter and preparing for spring. In May the Hindenburg exploded in flames above Lakehurst, New Jersey, and, as the former King Edward III prepared to marry Wallis Simpson, his brother was crowned King George VI at Westminster Abbey. Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, began their round-the world flight on June 1, but one month later, they vanished into history over New Guinea.

Another summer began and ended, and in September, the trips up Ridge Street resumed, Seppie brought woolens out of storage, and Peachie readied gardens for winter. At the end of the day he would go home to Albert and Eugene and the Daily Progress, make dinner in the warmth of the kitchen, and wait with them for Seppie’s step on the porch.

And then, in November, everything changed.

* * *

In those days, from the Rotunda to the bottom of West Main Street, there were no stop signs or traffic lights or anything to stop a young man who felt like racing his car down the street. On the afternoon of November 17, 1937, Albert and Eugene were alone in the house when a man came to tell them that Peachie had been struck by a car as he came out of Pollard’s Barber Shop.

As darkness fell, the boys waited for their mother to come home. She found Peachie in the basement of the university hospital, where he had been taken to a ward for blacks. Three days later, he died. After a funeral at Ebenezer Baptist, Peachie was buried next to Maggie in Oakwood Cemetery, in the section fenced off from whites. There was no obituary.

On Monday, November 22, the Progress reported that the driver, a UVa student named Henry Barbey, had been found not guilty of the “technical charges” that had been lodged against him. The student’s father, Pierre Lorillard Barbey of Tuxedo Park, New York, arranged through a local lawyer to pay whatever was left on the mortgage and Seppie’s other outstanding bills.

Seventy-seven years later, her son’s voice rises as he asks what the white lawyer, whose gardens Peachie had tended, did not: But what about the bills that would come the next day?

* * *

Seppie remained in the house on Dice Street for another 35 years, long after Albert and Eugene had grown up and moved on. She watched as Dice Street was paved and electricity came to all of the houses—along with running water and indoor plumbing—and cars began to line the street. From morning to night, sounds from the radio Albert and Eugene had saved up to buy her after Peachie’s death drifted out from the kitchen.

And for 35 years, she cared for Peachie’s garden; she clipped the walls of his jewel-box garden just the way he had liked them, and moved through the seasons, surrounded by the sense of him at every turn. She tended his garden until 1972, when urban renewal came with its machinery, and the rock walls and evergreens and garden were torn from the earth and the last signs of him vanished. The City sold the lots to a developer, who built houses that have not aged gracefully. Seppie moved to 913 Ridge Street, and died in 1974.

* * *

“I remember him to be very proud of his two boys,” Eugene says—but it’s hard to describe the man he knew so long ago, and only for 10 years. On another day he reaches for a yellow tablet and sketches the lines of his father’s garden, drawing a circle in the middle and describing how, on summer days, he and Albert would clip the short hedges and their father would clip the tall ones. Then he falls silent, startled by the rush of emotion.

The boys grew up and left for college, but when they came home no whites called them “Mr.” “They’d picked up their parents’ attitudes,” Eugene says. “Maybe worse.”

Albert taught music and led the band for a year at Jefferson High before going into the army. When he was discharged two years later he took a teaching job in New York, but soon returned to Charlottesville to earn a master’s degree at UVa. In 1959 the elementary school he and Eugene had attended was torn down, but by then Albert had moved away again. He and his wife, Emma, settled in White Plains, New York, and raised two daughters; he taught for four decades before they retired to Midlothian, Virginia, to be near their daughter.

Eugene moved back to Charlottesville in 1953 with his wife, Lorraine—Lo—and their two daughters. “I got active instantly with civil rights,” he says, and recalls how some of the whites he’d known as children didn’t care for that. Let good enough be, he says, was their attitude; “I got to the point of resenting these people more and more.”

Eugene is celebrated now for his refusal to stop knocking on the door until it finally, grudgingly, began to open. In 1954, as soon as the Brown v. Board of Topeka decision had been announced, he worked to convince black parents to join him and other NAACP leaders in suing to desegregate Charlottesville public schools. The battle, which was bruising, lasted until the City lost its final appeal in 1962.

When Vinegar Hill was razed to rubble in the late 1960s, Eugene implored the City not to fall prey to the belief that relocating residents to public housing—Westhaven—was the solution. Then, in 1980, Dogwood Housing was born: When the City’s approach had failed resoundingly, Eugene and Lo convinced Albert and Emma to join them in buying 22 parcels from the Reverend E.D. McCreary, Sr., and the 62 dilapidated rental units that stood on them. Eugene restored the buildings and rented them to low-income tenants—and for the next 27 years, proved that his approach to low-income housing could not only succeed, but prosper both tenants and owners.

Over the years he has been honored, by blacks and whites, for continuing to knock on closed doors long after his knuckles were bloody. The tributes are gratifying, and spoken in voices that are pleasing. But lately he has heard other voices, and listens in disbelief.

The speakers point to Rosa Parks, who finally said no; they cannot understand why so many—so many faceless thousands—said yes: Yes, I’ll stand at the back of the bus; yes, I’ll stand so that you can sit. Some white voices say, Why did you do it? And some black voices, young and taut with bravado, say, I wouldn’t have done it. But they would have—because the price of saying no could be punishingly high.

So much has changed in 77 years; the invisible dividing lines on buses are gone, along with the signs reading “Colored” and “White” and the separate entrances around the corner. Yet so much has stayed the same—the staggering numbers of blacks in prison, the crippling disparities in diplomas and jobs, the corrosive failures of public housing.

The boy who lived on Dice Street grew up—but the memories, and the scars, remain.

26 comments

"When Vinegar Hill was razed to rubble in the late 1960s, Eugene implored the City not to fall prey to the belief that relocating residents to public housing—Westhaven—was the solution. Then, in 1980, Dogwood Housing was born: When the City’s approach had failed resoundingly, Eugene and Lo convinced Albert and Emma to join them in buying 22 parcels from the Reverend E.D. McCreary, Sr., and the 62 dilapidated rental units that stood on them. Eugene restored the buildings and rented them to low-income tenants—and for the next 27 years, proved that his approach to low-income housing could not only succeed, but prosper both tenants and owners."

Where are these strategies now as Charlottesville creates massive new housing projects on West Main? What will happen to the residents of 10th and Page after the Republic Plaza development is done? What will happen to the people of Fifeville once the West Main Development is done? Will thewre be affordable housing units in these new developments? Are the developers required to contribute to the Charlottesville Housing Fund and will that benefit low income people in Charlottesville with affordable housing?

Why is there not a policy in Charlottesville that requires a diversity impact statement to be produced on all large scale development projects?

"So much has changed in 77 years; the invisible dividing lines on buses are gone, along with the signs reading “Colored” and “White” and the separate entrances around the corner. Yet so much has stayed the same—the staggering numbers of blacks in prison, the crippling disparities in diplomas and jobs, the corrosive failures of public housing." Amen.

Barbara Nordin has contributed greatly to The Hook over the years and it is sad that this beautifully written article must be her last Hook contribution. I am sure she will continue to write amazing pieces but The Hook will not be there to publish them. What a loss for Charlottesville and all those who appreciate great reporting.

The story of Eugene and Albert Williams' boyhood and the tragedy of their father's death provides a riveting account of life in Jim Crow Charlottesville. It feels like the basis for an entire book.

Thanks to The Hook for bringing this kind of high quality writing to the people of Charlottesville. It will be missed.

I second Margaret's comments: this is a terrific piece of reporting on a long-overlooked page of Charlottesville history, the ignorance of which continues to stagger, cripple and corrode.

With the demise of this little weekly, I hope that such good reporting will continue to inform. Perhaps it is time for the staff of The Hook to join forces once again with the Mothership, the equally laudable "C'ville".

Delightful. I'd love to see pictures of West Main and Vinegar Hill from before it was razed, if anyone knows a resource. :)

“Miss Lucy gittin’ atter me fuh leavin’ de hoe an’ de rake outside—but she know ain’ no nigguh gwine steal nothin’ t’ wu’k wid!!”

And it's still that way today...

If you've got True Strength, pitch in!

There's a needle in the haystack. There's an easy way to find it.

It's my daddy's, and it's plenty sharp. As for mine, it's yeller and it needs a good grind.

I'd better just leave it there.

All in favor of having a certain mass commenter locked up and forceable drugged again raise your hands and say "aye!" You know who I mean and you know it's time.

Yes indeed Mr. Jones and I want to see the video of the blessed event!

Time for bed?

I'm cute and I'm fuzzy and I have better vision than you!

An Aye for an Aye and a Stephen Baldwin for yeller teeth!

Pills bury.

Ha ha!

Rising up to Heaven

Am I the reason?

pourquoi pas?

Seriously, I didn't. Someone else out there is trying to defame me and associate me with guns and ammo!

Probably because they're spying on me and my family and know my mom's going to France. I bet they even think it's funny.

Au contraire

I haven't tried to see if it floats yet, the nitrous balloon didn't work out.

Je ne pense pas que j'ai écrit ces deux derniers commentaires non plus.

Que pasa con este? Mis juevos in tu boca?

Mes couilles dans la bouche! (I wrote the previous comment too)