Double recantation: Is an innocent man in jail for the Crozet murders?

-

Robert Davis said he wasn't there the night Nola Charles and her toddler were killed. Now one of his accusers says that, too.PHOTO BY LISA PROVENCE

Robert Davis said he wasn't there the night Nola Charles and her toddler were killed. Now one of his accusers says that, too.PHOTO BY LISA PROVENCE -

Fire investigators say the fire at 6047 Cling Lane was deliberately set.ALBEMARLE CIRCUIT COURT

Fire investigators say the fire at 6047 Cling Lane was deliberately set.ALBEMARLE CIRCUIT COURT -

Nola Annette Charles was 41 when she was murdered in her bed.ALBEMARLE CIRCUIT COURT

Nola Annette Charles was 41 when she was murdered in her bed.ALBEMARLE CIRCUIT COURT -

William Thomas Charles, 3, was called Thomas by his family.OBITUARY PHOTO

William Thomas Charles, 3, was called Thomas by his family.OBITUARY PHOTO -

Jessica Fugett admits she killed Nola Charles, whom she considered a friend.PHOTO BY LISA PROVENCE

Jessica Fugett admits she killed Nola Charles, whom she considered a friend.PHOTO BY LISA PROVENCE -

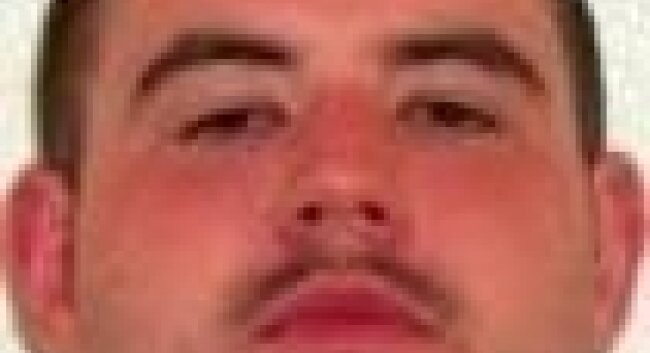

Rocky Fugett: "I know it's late, but I gotta do something."VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS

Rocky Fugett: "I know it's late, but I gotta do something."VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS -

At first, investigators couldn't see this charred knife in Nola Charles' back.ALBEMARLE CIRCUIT COURT

At first, investigators couldn't see this charred knife in Nola Charles' back.ALBEMARLE CIRCUIT COURT -

Did Greene sheriff candidate Randy Snead coerce a false confession from Robert Davis?Greene County Sheriff's Office

Did Greene sheriff candidate Randy Snead coerce a false confession from Robert Davis?Greene County Sheriff's Office -

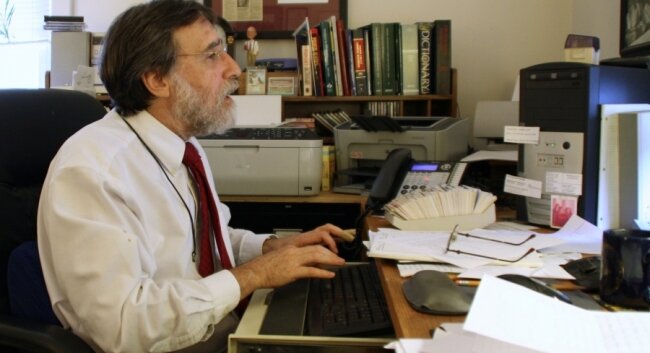

Attorney Steve Rosenfield has defended a lot of criminals, but he says he never believed Robert Davis was guilty.photo by Lisa Provence

Attorney Steve Rosenfield has defended a lot of criminals, but he says he never believed Robert Davis was guilty.photo by Lisa Provence -

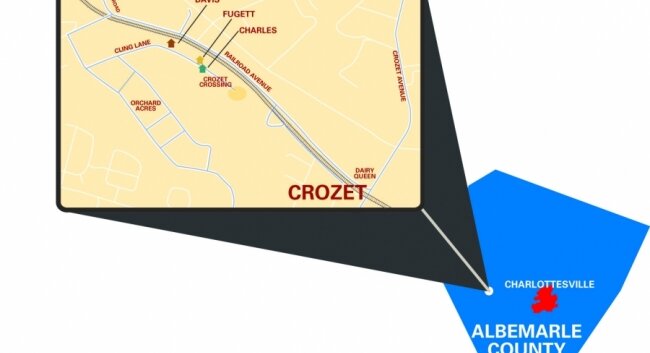

The Cling Lane neighborhood is within walking distance of downtown Crozet

The Cling Lane neighborhood is within walking distance of downtown Crozet -

Robert Davis just wants to go home.PHOTO BY LISA PROVENCE

Robert Davis just wants to go home.PHOTO BY LISA PROVENCE

It was the crime that rocked Crozet: a mother found stabbed to death in bed, her three-year-old son dead from the smoke of a cover-up fire. Amid whispers of witchcraft, four neighborhood teens were arrested, and three are doing time today in state prisons.

One of them, Rocky Fugett, now 27, admits he was there that night in 2003, for which he was convicted along with his sister and another neighborhood kid. Eight years later, Fugett says an innocent man is serving time for something he didn't do, and that man– Robert Davis– wasn't even there.

Davis' attorney, Steve Rosenfield, has long maintained that his client was coerced into a false confession, and with Fugett recanting, Rosenfield now seeks clemency from the governor. Fugett, serving a 75-year sentence on a guilty plea, says he has nothing to gain from changing his story.

As the clemency petition heads to Richmond, accounts differ and questions remain. But Rocky Fugett has another bombshell allegation: that another personplayed a key role in the events of that fateful night.

Crozet Crossing

Named for the peach trees that once grew there, Cling Lane is a cul-de-sac of 30 homes tucked between the railroad tracks and the older homes of Orchard Acres. Officially known as Crozet Crossing, the subdivision was planned in the early 1990s to provide first-time home ownership for hardworking families.

Much like Levittown, where the houses also began small and identical, the one-and-a-half story dwellings on Cling Lane are distinguished less by architecture than by individual touches such as bushes, low stone walls, and garden arbors.

On a street abloom with flowers and maturing plantings, house number 6047 gives no indication today of the horrors that transpired eight years ago. In the fall of 1994, Dennis and Nola Charles paid $87,500 for this last of the Crozet Crossing houses.

Eight months earlier, another family moved into the subdivision, folks who would play a central role in life of the Charles family– and in the death of Nola.

William and Teresa Fugett bought their house across the street and moved in along with their three children that January. Each family had two girls about the same age, and the moms quickly became best friends.

Nola Charles, known as "Ann" to family and friends, had grown up in Charlottesville. Her mother was from Hillsville in southwest Virginia, so her husband Dennis always called Ann a mountain girl.

"That's why we were in Crozet at the foot of the mountains," he says in a phone conversation from Albertville, Alabama, where he now lives.

They met in the mid-1980s when he was a used-bookstore owner earning extra cash as cable television technician. He came to her mother's house on Riverview Street to install cable when she was a 24-year-old still living at home and working as a laundress for the nearby National Linen Company. The two married in 1986.

Ann was a quiet person, "very meek, selfless," says Dennis. "She'd give you the shirt off her back."

Ann also had a creative side, writing short stories, making funny drawings, and adding her own personal flair to home painting projects, such as adding fish to the walls of a bathroom, he says. She stayed home with their two girls.

Their younger daughter was in elementary school when a boy was born. But by 2002, Dennis and Ann had separated. As a single mother, Ann took a job as night manager at the Dairy Queen/Amoco in the center of Crozet. Dennis regularly returned to the house, and he says they were trying to reunite as a family.

An odd friend

Across the street, Jessica Fugett may have been a normal child at birth, but when she was four years old, her parents became concerned about "staring spells," according to a court-ordered psychiatric evaluation.

As an eight-year-old, Jessica was "emotionally disturbed" and "developmentally delayed," according to an Albemarle County Schools report. There were problems with stealing, strained social relationships, and her IQ was described as "low average."

After a self-mutilation in 2000, Jessica was hospitalized for five days. The psychologist's report notes a refusal to go to school and a deterioration in hygiene. At age 14, she claimed she was having hallucinations that included seeing "a demon thing... big, with horns."

By the time Jessica Fugett entered Western Albemarle High School, she was heavily into Goth culture; as she later told police, she wore black for two reasons: "One is my religion. And the other is that black is a very slimming color."

The heavy-set freshman added that she was a witch and a Wiccan who also worshipped her older brother, Rocky.

Four years older, Rocky Fugett also was into Goth. A senior at Western Albemarle, he had been involved in several scrapes and had a juvenile police record for fighting. In addition, he had spent a night in jail for a trespassing event that included leaving a dead bird in a Crozet church.

Rocky Fugett admits he spent his days drinking and taking drugs, and that he had experienced blackouts. It wasn't uncommon to see him roaming the neighborhood late at night.

Bad February

Back in 2003, the U.S. invasion of Iraq was looming, and the month of February began with the disintegration of the space shuttle Columbia over Texas. On February 20, stage pyrotechnics ignited a nightclub in Rhode Island, where 100 people died in one of the deadliest nightclub fires in American history.

And in Crozet, there already had been a deadly fire that would haunt the community.

On the morning of February 19, 2003, a Wednesday, snow was on the ground, and school was canceled. Around 8:40am, a female neighbor noticing black smoke pouring out of the Charles home began pounding on the door, according to court documents. She was greeted by the elder daughter, Wendie Charles.

Wendie, 15, and her sister Katie, 11, both with rooms on the first floor, escaped their burning house. Another neighbor testified that she tried to run upstairs to where the girls' mother and baby brother slept, but the smoke stopped her after just three steps.

Crozet volunteer firefighters were the first officials to arrive. After subduing the flames and reaching the charred second floor, firefighters discovered something far more sinister than fire.

"The damage was done before we got there," remembers Albemarle Fire Chief Dan Eggleston, who got the call at his Crozet home.

Upstairs, investigators found Ann Charles face down in the bunk bed where her toddler son usually slept. The 41-year-old woman's arms had been bound behind her back with duct tape, and there was duct tape on her feet and ankles, which had been bound to the bed posts. Police forensic tech Larry Claytor, who today calls it one of the worst crime scenes he's ever seen, saw two aerosol cans on the bed and one on the floor.

In the adjacent bedroom, insulation had fallen, and the sky was visible through a hole in the roof, Claytor later testified. Under the debris in his mother's bedroom, responders found the body of three-year-old William Thomas Charles, who had died of carbon monoxide poisoning from smoke inhalation.

Claytor was still taking in the scene when he noticed a grisly detail he'd overlooked earlier: a knife in Ann Charles' back.

The knife was so badly charred, Claytor later testified, that he didn't initially notice it. What remained of it appeared to match those in a wooden knife-holder in the kitchen. The medical examiner later noted that Ann Charles' throat had been cut.

Investigators discovered that the upstairs smoke detector had been removed from the ceiling and the batteries taken from the kitchen detector downstairs. More ominously, the home's electrical breakers had been thrown.

Two siblings

In a rural community like Crozet, where the volunteer fire department serves as community hub, word of what happened spread like wildfire.

"It was devastating to the responders and to the community," says Albemarle Chief Eggleston.

Within two days, police picked up the Fugett siblings, 15-year-old Jessica and 19-year-old Rocky. After initial denials, the Fugetts admitted their roles. And they fingered two other Western Albemarle High teens: Tygue Herrmann and Robert Davis.

Rocky Fugett now says neither had anything to do with the gruesome invasion.

Herrmann, 17, who lived in nearby Orchard Acres, was held in juvenile detention for several months–- until prosecutors dropped the charges for lack of evidence. Davis, however, had given prosecutors something they weren't able to extract from Herrmann: a confession.

False confession conundrum

UVA law professor Brandon Garrett is an expert in false confessions, and he understands why many people can't fathom the concept that someone would confess to a crime they didn't commit. And yet when he studied the first 250 convicts exonerated by DNA evidence, he found that 40 had given false confessions.

"Typically, there's no DNA in murders," says Garrett, noting that such prosecutions usually depend on confessions.

False confessions tend, he says, to come from juveniles, the mentally disabled, or suggestible people. People tired or drunk are also vulnerable.

"The interviews in false confessions I looked at lasted over three hours," says Garrett. "If someone is exhausted, they think if they just go along with the interrogation, they can clear it up later."

One Virginia man, Earl Washington Jr., spent 18 years behind bars and came within nine days of execution after giving a false confession. After DNA showed another man was the perpetrator, he won a $1.9 million settlement.

Deidre Enright, who heads the Innocence Project at UVA Law School, says false confessions happen "all the time," particularly to young people.

"Kids don't know police are allowed to lie," says Enright. "Police can say, we have your DNA, your fingerprints, your friends say this. Police say we want to resolve this in your favor, but we can't do that unless you say you did it."

Enright declines to predict how Governor Bob McDonnell will react to a clemency plea because he hasn't faced one yet. But Virginia's track record for clemency on false confessions, at least as evidenced by what happened to the "Norfolk Four," isn't particularly forgiving.

In that case, four sailors falsely confessed to a brutal rape and murder. Even when the real killer was linked through a confessional letter and his DNA, Governor Tim Kaine would grant the four sailors only "conditional" pardons, which turned their double life sentences into time served and put them on parole.

Three convictions

Despite the urgings of prosecutors, Rocky Fugett decided that he wouldn't testify against anyone else and instead pleaded guilty to two counts of first-degree murder. In November 2005, he was sentenced to 75 years.

His sister, Jessica, was initially declared mentally incompetent to stand trial, but after a psychological evaluation, she went to trial and she was found guilty of two counts of first-degree murder, arson, and breaking and entering. At her 2006 sentencing, the prosecution showed a news clip of her smiling and waving at television cameras after her guilty verdict. Jessica got 100 years.

"She's seriously not right," Rocky told police early in his first interview. Eight years later, he says that Jessica seemed sort of "excited" the day after the murders.

The third person serving time is Robert Davis, 18 at the time. Arrested shortly after midnight on the morning of February 22, he was interrogated for more than five hours, beginning around 2am. As the transcript shows, he insisted dozens of times he had nothing to do with what happened in the Charles house, repeatedly offered to take a polygraph test, and said that he was tired and just wanted to sleep.

With his legs shackled, he complained he was cold, and it was almost 7am when Davis asked a fateful question of his interrogator: "What can I say I did to get me out of this?"

In September 2004, Davis entered an Alford plea, which allowed him to maintain his innocence while acknowledging that the prosecution had enough evidence to convict him.

Rocky recants

Rocky Fugett now resides southeast of Petersburg in Sussex II State Prison. In late April of this year, he meets with two reporters– one from the Hook and one from the Daily Progress– to share his story.

Speaking via teleconference at the medium-security facility that bans recording devices, cameras, and face-to-face meetings, Rocky appears to have lost weight since his perp-walk pictures of eight years ago. The first words he utters are about Davis.

"He wasn't there during any of this whole situation," says Fugett, "not in the slightest."

Although Fugett and Davis both lived on Cling Lane, both attended Western Albemarle, and were about the same age, they were the opposite of buddies. Fugett admits that he beat up Davis "six or seven times."

Fugett describes Davis as easily manipulated, a trait evident long before he ended up in a police interrogation room.

"He's weak minded," Fugett says. "You're with him 10 minutes, and you can get him to do anything you want."

Fugett is not quite sure how Davis first became a suspect, but he believes his sister probably was throwing out names during her interrogation, which occurred the same day as his.

Rocky was brought in from school for questioning. Almost immediately, after claiming he saw two guys get out of a car on Cling Lane the night of the murders, according to a transcript of the interview, he tearfully tells police, "In all honesty, it may have been my sister."

Expanding the net was not something they planned, Rocky says, but once police started asking him whether Davis and Herrmann were involved, he says he enjoyed the idea of sharing the blame.

"I didn't like either of them," Fugett says. "The cops would suggest something, and I'd say, sure."

What Fugett says he never expected was for Davis to confess.

"That one kind of messed me up," says Fugett. "He's a dumbass, and I really don't like him, but he doesn't deserve this."

Fugett claims that as far back as his own arraignment, he tried to tell the interrogator, then Albemarle Police Detective Randy Snead, that there were serious wrongs about the information he'd fed police.

"He said that doesn't matter now," Fugett says.

Snead, now with the Greene County Sheriff's Office, referred comments to the Albemarle County Police Department, which did not comment on the case other than to say they're open to new information.

He'd take a beating

At the time of the killings, Robert Paul Davis was living at 6148 Cling Lane with his mother, Sandy Seal, who had separated from his father when he was three.

"I raised him by myself," says Seal, now living in Waynesboro. "I worked two and three jobs to keep a roof over his head."

Davis was a senior at Western Albemarle that year, and although he was on the football team, Seal describes her son as a gentle giant.

"He's a big boy, but he doesn't know how to fight," she says, noting that she wouldn't allow him to fight, even though he attracted bullies like Rocky Fugett.

"He'd stand there and take a beating," his mother says. "I'd had Rocky Jr. arrested a time or two because several times he jumped Robert on the bus.

And although he was 18 at the time of his arrest, "Robert had the mind of a 14- or 15-year-old," says Seal, who had originally enrolled the boy at Ivy Creek, a special education school run by Albemarle County. There, the school resource officer was a cop named Randy Snead.

The arrest and interrogation

On that Friday, his last day of freedom, Robert Davis awoke around 7am to go to school. Later, he went out bowling and was spending the night with a friend in the Shenandoah Valley. He was just going to bed when his mother called and asked him to meet her at the Staunton Wal-Mart.

At 1am in the store's parking lot, his friend's car was suddenly surrounded by police with guns drawn. Robert was forced to the ground and arrested.

"They wouldn't tell me why I was arrested," he tells a reporter during an interview at Powhatan Correctional Center, where he's now incarcerated.

The post-arrest interrogation began at 1:57am, according to a transcript. Because Davis knew Snead as his resource officer from school, he says he viewed him as a trusted figure.

At 2:16am, Snead and the other investigators inform Davis that the charge is murder. Over the next four hours, according to the transcript, he denies involvement in the crime 78 times and denies being at the Charles house 26 times. Another 26 times, he insists he's telling the truth. Five times he offers to take a polygraph test, and he repeatedly says he's tired, uncomfortable from the shackles, and wants his mother.

"If you all are ready to put me in jail, put me in jail right now," he says at 3:42am, "because I'm tired, and I'm ready to go to sleep."

Davis insists to investigators that he knew Ann Charles only from seeing her at her job at the Dairy Queen/Amoco. And he tells them he didn't get along with Tygue Herrmann or Rocky Fugett.

"I don't associate with Rocky," he says. "I've had a problem with Rocky all my life."

And when they ask him why the other suspects would say he was there, Robert says simply, "Because they don't like me."

More interrogation

Despite the shackles, Davis falls asleep– briefly. He's awakened by Snead, who informs Davis that only the "truth" can keep him from the "ultimate punishment."

In a memorandum filed several years ago to suppress Davis' confession, lawyers Rosenfield and Denise Lunsford, the latter now the Albemarle commonwealth's attorney, argued that his confession was false, coerced, and that his incriminating statements had been "spoon fed" by Snead.

On the transcript, Snead tells Davis: “There’s an item that you touched all right, that left some particles on it, did some damage to somebody."

Davis offers–- incorrectly–- that the object was a bat; he later calls it a "clubbing device."

The medical examiner's report would show that Charles had suffered blunt trauma injuries to her skull, and Jessica Fugett later led investigators to an iron pipe consistent with those injuries.

When Snead asked Davis who hit Charles, he responds, "I believe it was Tygue."

"You don't know who you were with upstairs?" asks Snead.

"I was with two big figures," Robert replies.

Snead reminds Robert that four people were there, not three, according to the transcript of the interrogation.

When contacted by a reporter, Snead says he can't comment on allegations that Robert Davis' confession was coerced.

Coerced compliance?

Jeffrey Aaron, a clinical and forensic psychologist who testified at the 2004 hearing to suppress the Davis confession, explains how "coerced compliance" works.

"They know they didn't do it," says Aaron, "but they confess to escape from an adverse situation."

Although he declines to unequivocally call Davis' statement a false confession, Aaron says the course of Davis' interrogation shows factors typical in the research on such behavior, beginning with the vulnerability of the accused. Aaron notes that the Davis interrogation began late at night after a series of stresses, starting with the gunpoint arrest and moving on to deprivation of sleep, food, and comfort.

"While Robert was legally an adult, he kept asking for his mother," says Aaron. "That would suggest vulnerability."

The judge determined that the confession could be allowed in court because, according to Virginia law, it's up to a jury to determine whether it's false, attorney Rosenfield explains.

With the prosecution also vowing to have Rocky testify that Davis was present, Rosenfield– who helped Earl Washington win his civil lawsuit– recommended that Davis take the Alford plea and its 23 years rather than risk a life sentence.

Prank gone wrong?

Jessica Fugett, now in Fluvanna Correctional Center for Women, insists that Robert Davis and Tygue Herrmann were present that night. "I've maintained that story," she explains, "for eight years."

Jessica Fugett acknowledges that she can't really explain why Robert Davis and Tygue Herrmann, two enemies of her brother, would agree to join a murderous rampage.

"I don't know," she says. "I just saw them in the house."

The 24-year-old agrees with her brother about another thing.

"I was the one who killed her," says Jessica. "I broke in and killed someone I really liked. It seems so stupid."

Jessica also offers a different motive for the senseless evening.

"Rocky said [Ann] was talking shit about my mom and said, 'Let's go kill her,' and I said, 'Why not?'"

It turns out that Jessica had named yet another teenager during her interrogation back in 2003, but Jessica now says this alleged fifth conspirator had nothing to do with the crime.

"I was just rattling off names," she tells a reporter.

Innocence project

Rocky Fugett first came forward in 2006 in a letter to Davis' attorney Rosenfield: "I feel the information in my possession would help change the outcome of his conviction," he wrote. Today, Rocky Fugett says he didn't have any come-to-Jesus moment about reversing his stance.

"I don't really believe in God, but I felt I can't let this ride," he says. "I should have stopped it back then."

Rosenfield, who specializes in civil rights and capital cases, and who is president-elect of the Charlottesville Albemarle Bar Association, says he waited until Jessica Fugett's appeals were complete before pursuing clemency in the hope that she would "bolster her brother's truthful account."

Davis' mother, Sandy Seal, says she sat around the Fugetts' kitchen table many times when they shared the terrible bond as parents of accused killers, and she says both parents told her that both of their children exonerated Davis. Later, however, she says their father, William Fugett, screamed at her in the Dairy Queen, "If my children have to be there, yours does, too."

William Fugett declined to be interviewed.

Jim Camblos, who was the commonwealth's attorney during the prosecutions and is now a Waynesboro prosecutor, declined to comment on Rocky Fugett's allegations, saying only, "We charged those we had credible evidence against. It was a very, very difficult and emotional case."

As for Snead, his career has moved upward. Despite getting involved in an out-of-jurisdiction shooting of a 19-year-old cop-car thief last year, he holds the the rank of major, and he's running for the office of Greene County Sheriff.

Another birthday behind bars

The rural countryside around Powhatan Correctional Center has well-tended lawns and historic houses. Robert Davis can't see any of that from his cell, although when he climbs to the third tier in the prison, he can glimpse the James River.

"I remember going tubing down the James," says Davis, who turned 27 late last month, and who seems remarkably positive for a man who's spent nearly a third of his life in prison.

"I have faith," explains Robert. "I'm praying. I hope something will touch [Governor McDonnell's] heart, and justice will be seen."

Although his special needs status allowed him to earn his Western Albemarle diploma from jail, and although he just graduated from prison print school, where he's learned how to run a press and do desktop publishing, Davis fears that his original career goal–- becoming a CNA, a certified nursing assistant–- could be derailed by the murder conviction.

"I always wanted to help people, and I feel there will always be demand for male nurses," he says. "I'm worried this stigma will stop that."

The hardest thing about his incarceration, he says, is being away from his family.

"It's torn them apart," he says. "Mom says she worries about me all the time, that I'll get beat up, stabbed, killed."

His mother, who used to work as a CNA, is now so disabled that she can't work, and she believes some of her ailments are the result of the ordeal. Unable to drive, and relying on a walker to get around, she says she could really use the help of a son who wants to be a nursing assistant.

"Robert needs to be at home for himself and me and his brother so we can be a family again," says Seal.

"It still hurts me," says Robert. "I'm trying not to cry."

He spends a lot of time drawing and reading–- fantasy, philosophy, history, and poetry. Walt Whitman is a favorite. "Sometimes I write my own songs, and I'm working on a poetry book," he says.

Robert was surprised when he heard Rocky Fugett had recanted his accusation, given that they hadn't gotten along in the past. "When I heard that, it was a complete mind blower," says Davis. "I never would have imagined."

If he's released, he already knows the first thing he'll do after he hugs his mom. "This might sound weird, but I want to slide through the grass. I'd like to get dirty," he says. "And I'd like to feed the birds with Mom. We used to get birdseed and throw it out on the porch and watch them through the glass door in Crozet."

While Robert Davis hopes for freedom, Rocky Fugett's hopes are more modest: to stay out of trouble and to get a job, like sweeping the jail floor, just to occupy himself for an hour. He doesn't see any second chances for himself, and says he's not going to blame drugs or alcohol for what he did.

"I don't have words to describe how bad I feel about this," says Fugett. "It's kept me up so many nights. It was senseless, and there's no reason it should have happened."

The original story was redacted August 25, 2013, removing information identifying the person Rocky Fugett alleged was involved in the murder of Ann Charles.

11 comments

Once again, as usual, the repeated theme throughout this story seems to be "no comment" by the police interrogators involved in this case. This bothers me a lot. They had plenty to say during the interrogations and trial.

I can understand Snead not wanting to get involved any further now, he doesn't want anything to jeopardize his chances of a victory while running for public office (sheriff of Greene County).

Schwertfeger remains "open-minded" about new information? But he refuses to speak now about the interrogations. Can't have it both ways, bud.

I guess this was a very tough case to investigate. I can only hope they didn't put an innocent party in prison.

By the way, Lisa ............. excellent story!

Funny, but recently I was watching an old Dateline NBC episode on the 'net concerning a story that took place where I grew up in Connecticut as a kid, concerning young kids that were 18, falsely accused of killing a boy that they didn't, by an enemy who didn't like them. And then police interrogations gone awry, where the cops admit they lied to coerce what seems to be false confessions. Which were later recanted. But it was too late, and now somebody's behind bars (for over 10 years now) who shouldn't be and the police won't budge. Here's the link: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/38348079/ns/dateline_nbc-crime_reports/t/cir...

This whole business of cops lying to kids and coercing false confessions after multiple hours of browbeating them and terrorizing them really angers me. Just reading the transcript of Robert Davis' so-called "confession" makes me wonder how much an idiot the cops had to be to think that was actually some kind of genuine confession.

Considering how much it costs to house an inmate every year, and how much prison overcrowding there is, you'd think that they'd want to get rid of as many inmates as they can. Oh but wait.....then that means they may run the risk of getting sued should Robert Davis ever be allowed out. They may have to pay millions in restitution. Ah, now it makes sense why it's "look the other way and throw away the key."

>:(

Also, I'm left wondering what in the heck was going on in the Fugett's home to produce two siblings that were this crazy? Apparently Jessica's even more crazy then Rocky, but still, both were very troubled. At least one shows remorse and seems to understand right from wrong, and stepped forward to do the right thing in attempting to exonerate somebody that he even admits he didn't like, but, it's the right thing to do. The other one though....I wonder how that happened. This article makes me wonder what the parents are like. What do they look like? What are their personalities like? The mom was best friends with Ann, but were there any indicators of her being off, enough so that it makes sense why her two kids became so messed up? What about the father? Well, I guess the one quote from the father William Fugett is pretty telling in terms of where he's coming from as a person: "If my children have to be there, yours does, too."

this seems like the cops just wanted to close a high profile case and jumped at anything they could. where where the miranda rights during this? why didnt the kids just ask to talk to someone after 8 hours of bs?

I know Robert and his mother personally. This has been a long drawn out ordeal for both of them. This was a horrible crime and anyone who was responsible should be punished to the full extent of the law. If Robert is innocent, he should be pardoned by the Governor and let go. If you have young sons or daughters and if they get into a situation like this, tell them to say "I WANT AN ATTORNEY" "I WANT AN ATTORNEY" "I WANT A LAWYER" over and over again to every question that is asked. All questioning has to stop at that time. Robert being a little bit slow and not knowing what to do did not do this so the so called questioning went on and on. No food, no water, no inhaler that he needed, also so cold in that room that he tried to wrap up in his jacket. The interrogator Snead knew Robert from his school and should have known that he was slow and would follow his lead and say what Snead wanted him to say. I wonder why Snead left Albemarle for Green County? HMMM. Maybe this case had something to do with it. I just hope that justice is done and if Robert is innnocent that something is done before long. If he is guilty, he is where he should be. Let the wheels of justice roll and do the right thing. This case needs to be reopened and all evidence be reviewed and if there is evidence that was not presented that would have helped Robert, let it be brought out now. I am praying for Ann's family and for Robert's that this will soon be over.

Nope, They're guilty.

No he's innocent. It's plain as the nose on your face -what a miscarriage of justice. I just hope if the Governor doesn't have the good sense to pardon him that the Innocence Project will step in.

I plan to personally write and ask for a pardon and I encourage other readers to do the same.

Great job reporting Lisa !

The Innocence Project has been very successful. Why not start a Guilty Project to help keep behind bars the many criminals who lie about their innocence in their appeals?

Deleted by moderator.

These type of over the top "interviews" happen more often than any LE agency will ever admit. The willingness to put an apparently innocent person in prison to further one's own carreer should scare the $%#@ out of anyone who has to interact with this deputy.