It was as bright as day the night Warren Raines was orphaned. "The lightning was so intense that it was like now," says Raines, comparing that night to the daylight of a drizzly September 8 afternoon, the day that would have been his mother, Shirley's, 80th birthday.

"If it wasn't for the lightning..." he pauses. "I didn't know what move I'd have to make next. You had to watch your back. Whole houses were floating by... cars, cows..."

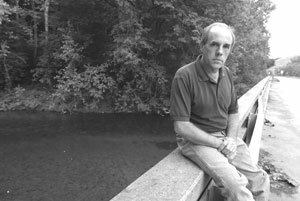

Raines, 51, sits on a rail of the bridge over the Tye River in the village of Massies Mill. Thirty-seven years ago, the warehouse where his father worked sat atop that bridge, washed 50 yards downstream by the flash flood that swept away Raines' parents, two sisters, and a brother.

That Tuesday in 1969-- still known as "the 19th" in Nelson County-- dawned a dog day of August, far removed from the cultural watershed known as Woodstock winding down to the north, far removed from the carnage known as Hurricane Camille that had just killed 174 people as it steamrolled through the Gulf Coast.

No one knew that Camille's fury wasn't quite spent.

What started as a seemingly typical rain that evening in what had been a wet summer had, by 2am, pushed the Raines family to flee their flooding home with four neighbor kids in tow.

"That night, this whole valley was Tye River," says Raines. Then 14, he survived the deadly waters by clinging to a willow tree. Not far away in another tree along Route 56, his older brother, Carl, held on, too, as Camille went on to take 150 lives in Virginia— 124 in Nelson alone.

Roar of heavens

In Massies Mill and nearby Tyro, 31 people died, according to a state report published the following year. The damage wasn't limited to that corner of Nelson, however. Nineteen miles away in Woods Mill at the intersection of U.S. 29 and Route 6, known until recently for Walton's Mountain Country Store, flood debris buried Route 29. More than 900 buildings were destroyed throughout the county.

Perhaps hardest hit was Davis Creek, where an estimated 40-plus inches of rain fell in less than eight hours, wiping away 22 members of the Huffman family alone. Official state numbers show 53 died in Davis Creek-- and 28 of those were listed as missing.

In the wake of last year's Hurricane Katrina, two books have been published detailing the devastation of Camille, until last August the benchmark of deadly hurricanes in the Gulf Coast: Category Five by Judith Howard, and Roar of the Heavens by Charlottesville resident Stefan Bechtel.

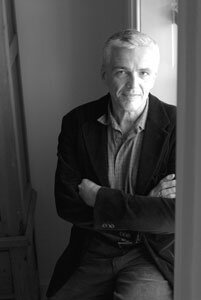

When Bechtel moved here around 20 years ago, he started hearing stories about the tragic deaths and devastation in Nelson County from Hurricane Camille. "It didn't register," he says. "How can you have a hurricane in Central Virginia? It seemed preposterous."

He read the historical marker at the Nelson County Wayside on U.S. 29 at Woods Mill that lists 114 deaths in Nelson and describes the 25 inches of rain— numbers that many claim are too low. "It was astonishing, all these deaths," he says.

"One of the things that really touched me-- whole families were swept away," says Bechtel, mentioning the Raines and the Huffmans. "The reason is that whole families were living together. Nelson County in the '60s was rural life preserved in amber."

Bechtel, author of six books, including three bold titles for men-- What Women Want, The Practical Encyclopedia of Sex and Health, and Sex: A Man's Guide-- turned to a different sort of writing challenge a couple of years ago.

A book about Camille's Nelson rampage, Torn Land by Paige and Jerry Simpson, came out the year after the hurricane. And there were several books detailing the Mississippi experience. But Bechtel thought there had never been a book that told the whole Camille story from its beginnings in Africa.

He chose a novelistic, day-by-day approach to the storm, interviewed survivors, and put it in the context of what was making news in America that August weekend, including the famous rain-soaked festival at Max Yasgur's farm in upstate New York. "All the images of Woodstock are rain," he says. "They're iconic."

He was also interested in the science of a Category 5 storm with winds that push 200 mph. "I wanted to tell the story from the hurricane's point of view, up 10 miles," he says.

In that he was assisted by scientist Jeffrey Halverson, who explains how, after Camille hit the Gulf Coast with brute force but seemed to be dissipating as it moved up the mid-Atlantic, it gained new life when it collided with the moisture-laden mountains of central Virginia and stalled, dumping so much rain that birds drowned in trees and many survivors had to cup their hands over their faces to breathe.

The Office of Hydrology of the Weather Bureau (now the National Weather Service) called Camille's downpour over Nelson "the probable maximum rainfall which meteorologists compute to be theoretically possible," Bechtel notes in his book.

UVA's state climatologist, Pat Michaels, turns up in Roar of the Heavens, and in fact, Camille changed his life. In 1969 he was a 19-year-old doing research on the circadian rhythms of five fiddler crab species in Ocean Springs on Biloxi Bay in Mississippi.

"I really like behavioral biology," says Michaels. "I really like weather and climate. [Camille] certainly pushed me toward weather and climate." He rode out the storm in a student dorm designed to withstand hurricanes.

The violent high winds and the 24.6-foot storm surge-- the highest recorded and thought to be even higher when it took out the three-story Richelieu Manor Apartments in Pass Christian-- are what wreaked havoc on the Gulf Coast.

But in central Virginia, it was the intense, unrelenting rain that poured for eight hours and unearthed the already saturated Blue Ridge mountains. Camille's official rainfall total is 27.35 inches in eight hours, says Bechtel. But he adds, "Everyone acknowledges that's a minimum."

At Davis Creek, the estimate is more than 40 inches. Exact measures at most locations in Nelson are impossible, given that rain gauges measure only a few inches-- and most of the gauges washed away.

Other receptacles provided some clues to the downpour's volume. For instance, a once-empty 55-gallon drum on the back of a pickup truck was found with 31 inches of water— in a location that wasn't in the center of the storm.

Compare that to Charlottesville's 2006 rainfall pre-Ernesto: 20 inches in eight months. "You're talking about eight months of rain in one night," says Bechtel.

"The water went up so quick," says Raines. When it started seeping into the family's house, they decided to find higher ground. The Woods, neighbors who lived behind them and whose own house was ringed by water, sent over the children: Donna Fay, Gary, Teresa, and Mike.

They all piled into the Raines' family car: father Carl, 52, mother Shirley, 42, Warren's brothers, Sandy, 9, and Carl, 16, and his sisters, Johanna, 18, and Ginger, 7. "After the water came up and killed the engine, we got out," says Warren Raines. "We had no idea it would rise as fast as it did." The group then took to Route 56.

"Walking on 56, the water was about knee deep," continues Raines. "In less than two minutes, it went from knee deep to four or five feet deep. The water was so swift you couldn't stand against it."

His father and Sandy and Johanna were found two days later. His mother was discovered in a barn about a mile away almost a week after the 19th, in time to be buried with the other three. "That was one of the ways they identified her, through her wedding band," says Raines. And little Ginger was found two weeks later, swept 17 or 18 miles away.

"It was peace of mind for my family that all were found," says Raines. But that wasn't the case for all the victims. Two of the Wood children-- Donna Fay and Gary-- are among the 32 people whose bodies were never recovered.

The house across the street washed off its foundation, and Raines believes it took the force of the current off their house. Water rose about five feet in the Raines house, but the second floor was untouched. "If we'd stayed in our house that night..." Raines says wistfully.

Après le deluge

The extent of the devastation to Nelson County was not immediately known to the outside world. And it wasn't the only area that flooded: Scottsville, Howardsville, Waynesboro, and Glasgow were all under water on August 20, the morning after.

With electricity and telephone lines down in those pre cell-phone days, with 100 bridges and countless miles of paved and gravel roads washed away, Nelson County was cut off from the outside world. Sheriff Bill Whitehead, trapped in a corner of the county along Route 151, radioed for help. His distress call was heard by the Augusta County sheriff's department, which sent a helicopter over and reported the disaster, Bechtel recounts in Roar of the Heavens.

Cliff Wood lives on the James River looking into Buckingham County, and he awoke that morning to see the James had flooded his fields. "The water was coming from the Tye River, which drains from Nelson and Amherst," he says. "The James had never flooded at that speed by one tributary. That was an indication of how much rain had fallen."

By virtue of being the only one of four Nelson supervisors who could make it to the county seat in Lovingston, Wood took charge of the rapidly assembling relief and recovery effort. "Local governments have a responsibility in those situations," he says. "That's how I got involved."

Tom Gathright was a geologist for the Virginia Division of Mineral Resources, working in its ground water section. Lovingston had lost its water supply, and he was asked to come down and pick a well site on day three after Camille. He describes the "matchstick pile of big trees" at Woods Mill on Route 29.

"It was a terrible mess at the bridge right at the mouth of Davis Creek, where 50 people were killed," he recalls. "A lot of them were in that pile."

He recounts how a machinery operator began clearing the debris at Woods Mill. The first time he picked up a load, he found a body. "They couldn't hardly get him back on that equipment," says Gathright.

"Fortunately I took my photographic equipment with me," Gathright adds. He took two short helicopter rides-- the newly built but unopened U.S. 29 bypass around Lovingston had been turned into an air strip-- and printed his photos that night. "I showed them to the state geologist, and he said, 'We've got to get in there.'"

With permission from the governor's office, Gathright was given helicopter and plane access.

"By day seven when I came in, three-quarters of the yellow heavy equipment in Virginia was in Nelson County," he says. "The wood was wet and muddy. You could hardly use a chainsaw for long because it would tear the blade."

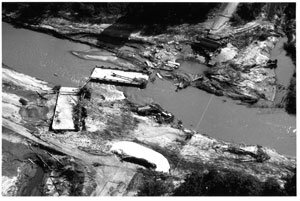

Bare strips exposing rock still dot the mountainsides in Nelson, and the earth loosened by Camille sent down tons of trees, soil, and boulders. When the ground gave way, the debris collected into impromptu dams, until the unrelenting mass of water caused them to burst.

Aerial photos of the Davis Creek area show swaths of stone running like a river of rock. While Camille was a once-in-a-lifetime disaster for mere mortals, in the history of this continent, such force is more like a once-in-a millennium event.

"In Nelson we dug up old deposits and ran carbon dating on them," says Gathright. "The youngest was 2,000 years old."

He points out that Rockbridge County on the other side of the mountains had slides, but it was a different geology that made for much cleaner debris, with less mud and fewer trees. "Trees can hold onto sedimentary rock much better than granite," he says. And that's the rock found on the Nelson side of the mountains.

Recovery

Today Phil Payne is the commonwealth's attorney in Nelson County. He was 15 in 1969, and his father, Dan, took on the grim task of finding the missing. In the first couple of days before more volunteers arrived, Phil and some of his friends went out on search-and-rescue missions, primarily because there was no one else, until his father decided it probably wasn't the best idea to send boys out on such a grisly job.

"It was pretty shocking," says Payne, whose team found three bodies their first day, including that of a 16-year-old schoolmate. "I don't think I'd ever seen a dead person before. It was disturbing. I can visualize every incident. I can see it now like a photograph."

He praises the efforts of those in the search parties, including Baptist minister John Gordon. "He was the chief lieutenant for my father in the body searches," says Payne. "You wouldn't know this guy had been pulling three-week-old bodies out of woodpiles."

The Mennonites became the unsung heroes of the disaster, manning many search parties and doing whatever had to be done.

"It was like magic, they were here so quickly," remembers Payne. "You had to look to find them because they weren't hanging around drinking coffee. They are highly revered in Nelson."

Search parties began depending on two reliable clues for finding the dead: vultures circling overhead and the stench of death.

When bodies were found, they were stored in a refrigerated trailer behind the funeral home in Lovingston. "That odor from that trailer was easily noticeable from 200 or 300 yards away," says Payne. "I just tried to avoid the area."

On the morning after Camille hit Nelson, Dr. Robert Raynor had gone to Waynesboro to make his rounds in the hospital, and was returning to a prenatal clinic in Lovingston when he was stopped by a state trooper on Route 151.

"That was the first time I knew how bad it was," he says from his clinic in Afton, where he still practices.

How bad were the injuries? "People either escaped it completely, or they died," says Raynor, who assisted chief medical examiner Dr. James Gamble.

According to Raynor, the deaths were pretty evenly split between drowning and blunt trauma from the tons of debris slamming into houses.

It wasn't just Nelsonians who died in Nelson. John Seal Jr. from Madison County, a 40-year-old truck driver for Crozet-based Morton Frozen Foods (later named ConAgra) was washed into the torrent at Woods Mill and his tractor-trailer cab-mate, Almond W. Herring, 35, of Crozet, died with him. Two truck drivers on their way from Waynesboro to Gastonia, North Carolina were also lost.

One thing the dead had in common: the force of waters stripped off clothes and even wedding rings, making identification all the harder. On most of the dead, "We didn't do autopsies," says Raynor. "The only reason for doing autopsies was to establish identification on 30-some bodies."

On eight of those, the efforts were unsuccessful— particularly strange for a county as close-knit as Nelson. The doctors concluded those folks weren't local residents. Raynor believes some of the unidentified were migrant workers between jobs. Because beans were found in some of the stomachs, Raynor concludes, "Four of the eight ate supper together."

Even more disturbing were those who were never found-- 37, according to the state historic marker. The 1970 state Flood Disaster: Review and Analysis pegs the number at 32.

"The fatality numbers on this are all over the map," says Bechtel. Official numbers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration are 256. "That's totally wrong," says Bechtel.

And the number of Nelson County residents who won't talk about Camille to this day: many.

Weighing Camille

NOAA calls Camille the "second most intense hurricane of record to hit the United States."

But Camille survivor Pat Michaels doesn't necessarily agree that Camille was Virginia's worst hurricane. In terms of percentage of people affected, he points to accounts of a 1667 hurricane that blew down 10,000 homes in southeast Virginia. "That sounds like all the homes in Williamsburg," he says.

Cliff Wood has lived on the James River all his life, and he saw the highest recorded flood there in 1972 from Hurricane Agnes, when the water rose to a record 34 feet and flooded downtown Scottsville-- on the heels of Camille's 30 feet in 1969-- prompting the town to look for federal funding for a levee. Hurricane Juan in '85 also raised the James higher than Camille. "But no one died in those floods," he points out.

Wood compares Camille to last year's Hurricane Katrina: "Our disaster covered about 200 square miles, Katrina 90,000 square miles." Another difference: "Back in Camille, it didn't occur to us to blame it on the President."

But in terms of loss of life, the differences are more staggering. Nelson County, population 12,000, lost one percent of its population. Two memorials stand on the courthouse lawn in Lovingston on either side of the flagpole.

"A marker for Camille recognizes it as Virginia's worst natural disaster," says Wood. "The Civil War monument commemorates Virginia's worst man-made disaster."

While family members and survivors have never forgotten Camille, the two new books have renewed interest in the events of 37 years ago, particularly after Katrina.

Phil Payne, like many of those listed in the index, has read Roar of the Heavens. "I couldn't put it down and read it in three nights," he says. "I'm a slow reader."

He thinks Bechtel did a good job of keeping the story moving. However, "Less attention was paid to some of the tension between some of the leaders," says Payne. "At the time, there were quite a bit of bruised egos and hurt feelings."

He also notes some factual errors, as did a Richmond Time-Dispatch reviewer, who points out that Warren Raines' sister did not date Linwood Holton, who was running for governor that year, but Linwood Hurst. And some residents were surprised to find a Kroger in their midst. Bechtel acknowledges the errors, and plans corrections in the paperback edition.

"But they were fairly minimal things," adds Payne. "They certainly didn't detract from the story."

Warren Raines' story is on the cover of the book, but he hasn't read the entire work-- yet. "I'm a very emotional person," he says. "I can only read so much at one time."

Although orphaned at 14, he didn't have the option of counseling after losing most of his family and his home in one night. "That sort of thing was unheard of," he says.

He still lives in the same corner of Nelson County, not far from Massies Mill, and about a mile back from the Tye River on higher ground. And when heavy rains, hurricanes, or remnants of hurricanes are predicted, "You get flashbacks," he says. "It brings back memories."

Raines has been interviewed many times, but he agrees to talk to yet another reporter. "If somebody doesn't talk about it," he points out, "people won't know what happened."

CORRECTION: Logistics make it impossible that truck driver John Seal Jr. would have been swept away from Woods Mill and found in Lynchburg, which is upstream. That error has been corrected.

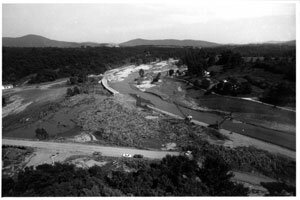

Debris from Davis Creek logjammed U.S. 29 at Woods Mill, which had just been dual-laned to the south. The building that would become Walton's Mountain Country Store is on the far right.

PHOTO BY TOM GATHRIGHT

Woods Mill today. Walton's Mountain Country Store, which traded on the fame of the popular television show, is now a nursery.

PHOTO BY SKIP DEGAN

Looking north at Woods Mill, where the converged Davis and Muddy creeks join the Rockfish River

PHOTO BY TOM GATHRIGHT

Nelson County Wayside (far right) was built at Woods Mill, and a state historical marker commemorates Hurricane Camille.

PHOTO BY SKIP DEGAN

Davis Creek converges with the Muddy after Camille across U.S. 29, just south of the intersection of Walton's Mountain Country Store and Route 6.

PHOTO BY TOM GATHRIGHT

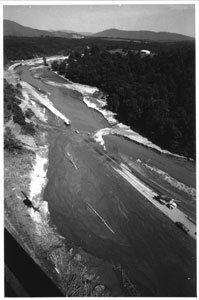

Entire families disappeared at Davis Creek, where 28 of the 53 dead were listed as missing.

PHOTO BY TOM GATHRIGHT

The ground gave way on the west side of 29 north of Lovingston. Geologists says such slides are common-- every couple thousand years or so.

PHOTO BY TOM GATHRIGHT

Waters in Roseland flipped the Bland Harvey house on its side.

PHOTO BY TOM GATHRIGHT

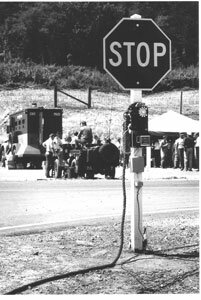

The newly completed U.S. 29 bypass around Lovingston hadn't officially opened, and it was inaugurated as a landing strip after Camille when most roads in the county were impassable.

PHOTO BY TOM GATHRIGHT

Short-wave radio became the main method of communication to the command center in Lovingston because most phone lines in Nelson were down.

PHOTO BY TOM GATHRIGHT

Warren Raines shows where his father's warehouse landed on the Massies Mill bridge that had just been constructed in 1968 and withstood Camille's swelling of the Tye.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The historic marker at the Nelson County Wayside off U.S. 29 demonstrates how hard it is to get accurate numbers in a disaster like Camille. Roar of the Heavens author Stefan Bechtel tallies Nelson deaths at 124, as does the state's 1970 analysis, which figured 32 people were missing. And survivors say the rainfall far exceeded 25 inches.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

At the courthouse in Lovingston, two memorials commemorate the worst disasters to hit Nelson County: the Civil War and Hurricane Camille.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Stefan Bechtel, author of Roar of the Heavens, couldn't believe so many people had died from a hurricane in rural, decidedly non-coastal Nelson County 37 years ago.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The Route 639 bridge over the Rockfish River is one of more than 100 bridges Camille took out in Nelson County.

PHOTO BY TOM GATHRIGHT

SIDEBAR- Progress plus: How Camille played out in the paper

The headline in the first edition of the Daily Progress after Camille struck gave little indication of the horror that had roared through Nelson County: "Rain worst in 15 years; Floods isolate Scottsville." Scottsville? The slow release of Nelson news may strike modern readers as odd, but there's an obvious explanation.

"As far as communications go," explains Nelson County businessperson Russ Simpson, "there were none. The widespread flooding cut off a lot of things-- including roads and telephone lines."

Former Progress reporter Rey Barry remembers that time well. He had driven to Richmond on August 19 to cover the hotly contested Democratic gubernatorial runoff. On his way back to the newsroom around midnight, rain was falling steadily, and he encountered several stretches of standing water along the roadway. "All we knew," Barry says, "was... something."

With communications washed out, it seems understandable today that that first story in the afternoon edition (it was an afternoon paper then) of the August 20 Daily Progress noted just two drownings: one in Amherst and one in Nelson. The only Nelson photo came from the Associated Press.

"The media couldn't get in," Simpson says. "The only way you could get in was by helicopter."

The next day, while Governor Mills Godwin hovered over Nelson in a chopper, downtown Scottsville was under more than 20 feet of water, and throngs of rubberneckers caused Scottsville's Town Council to declare a curfew. The Progress hired an airplane for reporter Nancy Talmont and photographer Jim Carpenter.

"As soon as it was obvious that Nelson was hardest hit," says Barry, "Nelson was blanketed with coverage."

The blanket coverage began on the afternoon of August 21, with nearly a dozen stories and as many photos-- and word on the catastrophe in Nelson was starting to spread.

"Nelson death toll high" screamed a Progress headline. "50 persons unaccounted for," read a photo caption. "State Police report at least two dozen deaths-- possibly several more may be dead, police say." Still, the top story suggested this was merely "the heaviest rainstorm since 1954's hurricane Hazel."

The op-ed page was out of touch, as the August 21 lead editorial was headlined "Tragedies in the Water," but the topic was recreational safety on Smith Mountain Lake.

On August 22, the Progress began its first on-the-scene disaster reporting. "Stricken village counts its dead," read one headline, and a reporter who later told the tale in book form, Jerry Simpson, penned his first story from the devastated county.

The following afternoon, Saturday August 22, the Progress printed a Lovingston-datelined piece by reporters Nancy Talmont and Ann Norris that began ominously: "They were counting the dead here yesterday. It's not the usual Friday afternoon occupation, but yesterday was like no other Friday." That day the newspaper also ran a photo of Nelson Sheriff Bill Whitehead comforting Brenda Zirkle, a Tyro girl who lost both parents and a brother. The reported toll was now 44 dead and over 80 missing. Horrific tales included the story of living husband and his dead wife buried to their necks in mud. By the time the man was dug out, he too had died.

The microfilmed editions in the basement of the Jeffeson-Madison Regional Library, reveal one sobering fact: an almost complete lack of obituaries. In the two weeks after the storm, what is arguably the Piedmont's newspaper of record carried just five death notices for nine flood victims. Simpson says difficulties in finding bodies and identifying them were just two factors that made funerals so rare. He ought to know, as his aunt, uncle and five first cousins-- an entire family of seven living in the mountainous Davis Creek community-- died in the deluge.

"Burying was a priority, but it wasn't the highest priority," says Simpson. "They didn't have enough caskets here, for one thing, and the ones they had were filled with mud because a slide went through the funeral home."

On August 24, the Progress went northward and ran another large photo of the washed-out bridge and dam at the Blue Ridge Shores gated community in Louisa County. (An earlier aerial by Carpenter of the roiling waters in action would go on to win a state award.)

That same day, in what has to rank as one of the worst-timed marketing moves locally, the new Fluvanna development called Lake Monticello ran a full-page ad of a vast horizon across a wide lake. The unfortunate headline? "The view from your place."

The August 25 edition of the Progress reported that two entire families-- the Wootens and the Burnleys-- were still missing from the village of Norwood. On the 27th, there was a photo of a backhoe digging a triple grave at Jonesboro Church in the town of Roseland. A list of the missing and a plea for more information from the public was the top story on the 28th, and another front-page headline asked if this ranks as a "100-year flood." (One weather expert now calls it a 2,000-year flood.)

On August 31, reporter Jerry Simpson noted that agricultural losses in Nelson might reach $2 million, and the search for bodies began winding down. The September 2 edition of the Progress was the first with no flood story on page A-1, but flood stories continued to appear both on the cover and inside the Progress for the next several weeks.

Carpenter remembers renting a 1965 International Harvester Scout from H.M. Gleason & Son a few days after his airplane ride. He says he was struck by the rescue workers in the soiled and torn white jumpsuits they wore back then-- and by their tired faces.

"Like a lot of photographs you've seen of firefighters after the World Trade Center fell," says Carpenter, "they had blank looks. They just didn't have any expression left."

Russ Simpson eventually attended a funeral for his aunt, uncle, and five cousins-- even though four of the children's bodies were never found. School in Nelson started late and required Saturday classes to make up for lost time.

"This thing just blew us away," says Simpson. "This was Nelson County's 9/11."

The Daily Progress wrestled with the horrors.

PHOTO COLLAGE

#